“I like to give a message of hope. That’s why I do social work,” says Jide Fayase as we discuss his team’s work supporting people with severe eating disorders.

“I remember a young woman who’d been in and out of hospital since her early teens. At one point she disappeared for a week. People feared she was dead. She’d run away because she didn’t want to eat. We worked with her and helped her stabilise her weight. Eventually she went to college, she got out of hospital. She started dreaming again. That’s very powerful for me.”

Jide is the principal social worker for the specialist eating disorder service at South West London and St George’s NHS mental health trust. The service, one of the world’s largest and longest established of its type, offers inpatient treatment, day care and community support. It serves its south London community but also accepts referrals from across the UK.

As part of the service’s multidisciplinary team, Jide works alongside doctors, nurses, psychologists, healthcare assistants, an occupational therapist, a family therapist, an exercise therapist and a dietician. His work is split between Avalon Ward, the service’s 18-bedded inpatient unit, and the community, where he runs carers groups and family support sessions.

Physical and mental harm

People assume that eating disorders are just about people wanting to be stick thin but it’s far more complex than that

Most patients on Avalon Ward are detained under the Mental Health Act. While the service as a whole will see a range of eating disorders, the majority of patients on the ward have anorexia nervosa – a mental health condition and eating disorder that leads to people dangerously restricting their eating in an attempt to force their weight as low as possible. The lack of food can trigger acute kidney failure, liver damage and heart failure. Put simply, anorexia can be fatal.

“Physical health is consistently a risk element in this area of work,” says Jide. “We have a medical bay on the ward to monitor people’s bloods, heart, kidney function, liver function. And when I assess someone, I’m thinking not just about mental disorders but also physical health risks, particularly if someone has a BMI of 13.5 or below [a BMI of between 18.5 and 24.9 is generally considered ‘healthy’].”

An ‘incredibly complex’ field

This interplay between mental and physical health is just one of many reasons working in eating disorders is “incredibly complex”, says Jide. Clients often come from middle-class backgrounds, although that’s changing, he says. Most patients – although not all – are women (when we meet two men are being treated on Avalon Ward). Some people present with a history of sexual or emotional abuse. Issues of identity can be present and child protection or safeguarding concerns can feature. In short, there’s often a lot for a social worker to unpick.

“People make a lot of assumptions about eating disorders,” says Jide. “They think it’s all about people wanting to be stick thin like a model but in my experience a lot of the time it’s actually a sort of coping mechanism. It’s about managing emotions. It’s very, very complicated.

“I used to work in substance misuse and a lot of the clinical interventions in this job are actually very similar to substance misuse. Ultimately social work is about connecting with people in all kinds of situations. You connect with the pain, you connect with the loss, you engage. Human suffering is human suffering.”

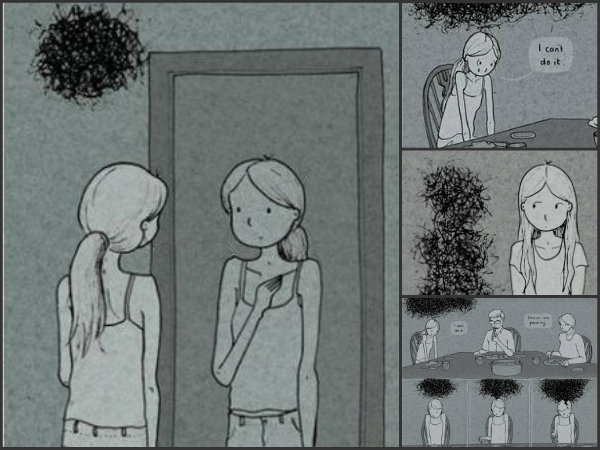

Eating disorders take a serious toll on the mind, leading to people doing serious harm to their bodies. People with a very low weight can often have cognitive distortions that can be incredibly destructive to their wellbeing, explains Jide. It’s almost like the mind operates as a cruel hall of mirrors, convincing the person that they are overweight and that everyone around them is slim, no matter the abundance of evidence to the contrary.

Eating disorders take a serious toll on the mind, leading to people doing serious harm to their bodies. People with a very low weight can often have cognitive distortions that can be incredibly destructive to their wellbeing, explains Jide. It’s almost like the mind operates as a cruel hall of mirrors, convincing the person that they are overweight and that everyone around them is slim, no matter the abundance of evidence to the contrary.

Working with the emotional trauma underpinning disorders is essential but there can also be cases where emergency interventions are needed on the physical health side of things. In extreme cases, some patients at Avalon Ward will require intensive care that includes nasal-gastric feeding. The treatment, both controversial and life saving, sees people fed via a narrow plastic tube that is inserted through their nose and connected to their stomach.

‘Community work is vital’

So what is the role of a social worker in this eating disorder service? For starters, Jide will take part in ward rounds and care planning. He’ll write reports for mental health review tribunals and liaise with psychiatrists and Approved Mental Health Professionals around Mental Health Act assessments. He’ll also fight to make sure that the relevant NHS trust or local authority provides patients detained under the Act with access to the independent advocacy they are entitled to.

In the community, he’ll work therapeutically with people, many of whom will have spent long spells in hospital. A lot of work is also done with family members and carers. Jide runs carers groups twice a month. For people that don’t feel comfortable attending the group, he’ll do a one-to-one session or run a joint session for carers alongside the family therapist.

“All of that [community] work is crucial because being on a ward a lot of the time can feel quite medicalised. The focus is on the illness, on treatment, on cure. For me, I’m always thinking, what’s the quality of life for this person? Can we get them engaging back in the community, even at a low level?,” says Jide.

“I try to bring the carers in as experts too. How do they see the situation? How are they experiencing it? We have a multidisciplinary team and the parents, the carers are part of that team.”

For all its rewards, the job can also be testing. Supporting people with severe and enduring mental illness means coming face-to-face with “a lot of distress, a lot of pain” every day, Jide acknowledges. With children of his own, he says he finds it particularly hard knowing that some of the service’s younger patients have spent years in hospital missing out on opportunities (“You just know they have so much to live for,” he says).

Reflective sessions held every couple of weeks are crucial to staff having an opportunity to “offload” and get support for their own wellbeing, says Jide. Keeping your practice “alive and fresh” by constantly trying to learn and develop also helps, he says.

A chance to do ‘real social work’

Before I leave, Jide tells me how he remembers what it was like to be starved of opportunities to do the kind of direct client work he does now. In a previous social work role he’d been “plonked into what felt like a call centre” and the experience felt closer to a customer service job he’d held years ago than frontline practice. He finds his current role, he tells me, so satisfying because it allows him to do “real social work”.

“I really missed working with clients. The thing I love about this job is being able to actually apply the skills I trained in. When I trained, the emphasis in social work was about communicating, engaging, assessing and making connections with people. I love that,” he says.

“I also like being able to bear influence in care plan review meetings, advocacy and ward rounds. Coming in to this service as the only social worker back in 2011 was – to be honest – quite difficult at first. But now I feel very strongly that my views are respected as a social worker. That’s quite amazing.”

The illustrations in this piece are from Lighter than my shadow, a graphic memoir by illustrator and author Katie Green (www.katiegreen.co.uk). Images are used with Katie’s permission. For support with eating disorders contact Beat at www.b-eat.co.uk

A trauma-informed approach to social work: practice tips

A trauma-informed approach to social work: practice tips  Problem gambling: how to recognise the warning signs

Problem gambling: how to recognise the warning signs

Find out how to develop your emotional resilience with our free downloadable guide

Find out how to develop your emotional resilience with our free downloadable guide  Develop your social work career with Community Care’s Careers and Training Guide

Develop your social work career with Community Care’s Careers and Training Guide  ‘Dear Sajid Javid: please end the inappropriate detention of autistic people and those with learning disabilities’

‘Dear Sajid Javid: please end the inappropriate detention of autistic people and those with learning disabilities’ Ofsted calls for power to scrutinise children’s home groups

Ofsted calls for power to scrutinise children’s home groups Seven in eight commissioners paying below ‘minimum rate for home care’

Seven in eight commissioners paying below ‘minimum rate for home care’

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Comments are closed.