The Law Society has issued a summary of 27 deprivation of liberty legal cases, including seven it advises should not be followed, in a bid to help social workers, best interest assessors and other professionals comply with a landmark Supreme Court ruling.

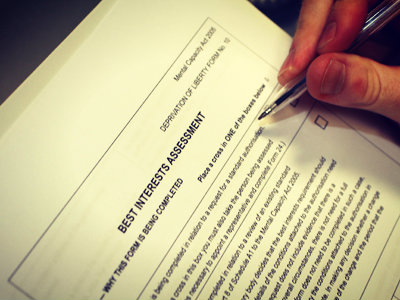

The summary of key cases, which can be downloaded here, is included as part of new comprehensive practice guidance on deprivation of liberty published today. The guidance, which was commissioned by the Department of Health, also contains practical case studies involving a range of scenarios including care homes, hospitals, supported living, and care for under 18s.

The document aims to help social workers and other practitioners handle the ongoing practical fallout of the landmark ruling issued by the Supreme Court last March in the linked cases of P v Cheshire West and Chester Council and P&Q v Surrey County Council.

The ruling (see below) effectively lowered the threshold for what constitutes deprivation of liberty in care and triggered a surge in cases. Today’s guidance aims to help practitioners identify when the treatment of someone amounts to a deprivation of liberty in the wake of the ruling.

Care placements in care homes and hospitals that meet the deprivation of liberty threshold must be authorised under the deprivation of liberty safeguards. Cases outside of care homes and hospitals, notably supported living, must be authorised via the court of protection.

The full guidance documents

- Deprivation of liberty: a practical guide (full document)

- Chapter 1 – introduction

- Chapter 2 – the law

- Chapter 3 – Cheshire West

- Chapter 4 – the hospital setting

- Chapter 5 – the psychiatric setting

- Chapter 6 – the care home setting

- Chapter 7 – supported living

- Chapter 8 – at home

- Chapter 9 – under 18s

- Chapter 10 – summaries of key cases

- Chapter 11 – further resources

About the Supreme Court ruling

The Supreme Court’s judgement in the linked cases of P v Cheshire West and Chester Council and P&Q v Surrey County Council in effect lowered the threshold for what constitutes a deprivation of liberty in care.

The court’s “acid test” said that a person who lacked capacity to consent to their care arrangements was deprived of their liberty, under Article 5 of the European Convention of Human Rights, if:-

- they were under continuous supervision and control;

- they were not free to leave, and;

- their care arrangements were the responsibility of the state.

The ruling rendered irrelevant factors that had been allowed for in the past, such as whether the person objected to their care arrangements.The Supreme Court also made clear that such a deprivation of liberty would apply in a domestic setting, as well as in health or social care placements.

The judgement was welcomed for extending key human rights safeguards to a broader group of vulnerable people. But it meant that, overnight, many people in care homes, hospitals and supported living arrangements suddenly met the threshold to have their care arrangements assessed or reassessed to see if they were deprived of their liberty and, if so, whether or not this was in their best interests.

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Comments are closed.