How would you improve the social work assessed and supported year in employment (ASYE)? [Multiple answers]

- Greater flexibility in support so the ASYE can be tailored to the needs of each practitioner (26%, 189 Votes)

- Assigning complex cases only when additional support is in place (24%, 176 Votes)

- Caseload set at less than the current 90% level (24%, 173 Votes)

- Increased frequency of reflective supervision (11%, 76 Votes)

- Tailored support for black and ethnic minority social workers (9%, 67 Votes)

- Dedicated groups in each local authority for black and ethnic minority social workers (6%, 41 Votes)

Total Voters: 722

The failure rate for the children’s assessed and support year in employment (ASYE) has fallen but black and minority ethnic practitioners remain less likely than white counterparts to pass the year.

Skills for Care’s annual report on the children’s ASYE for 2023-24 also showed that women were consistently more likely to pass the year compared with men, continuing another trend.

And despite the ASYE framework recommending that 10% of newly qualified social workers’ time is protected for learning, the report found that NQSWs’ loyalty to their teams was such that they often took on a higher-than-recommended caseload.

However, most ASYE leads, assessors and social workers surveyed for the report said the supported year had had a positive impact on the practice confidence of NQSWs and on outcomes for people using services.

Record numbers on the children’s ASYE

The report showed that record numbers of social workers – 3,203 – were registered on the children’s ASYE in 2023-24, up 12.6% on the previous year.

This is likely to reflect, in part, the fact that 2023 was a graduation year for the biennial Step Up to Social Work course, meaning there was a greater supply of graduates trained to work in children’s services than in the previous year.

The vast majority of participants (94%) were working in local authorities, with London and the North West the most represented regions, with 17% each of the cohort.

Falling failure rate

From 2018-19 to 2021-22, the failure rate for the children’s ASYE fell from 1.57% to 0.46% of participants.

However, the report showed that previous disparities in failure rates based on race or ethnicity, sex/gender and whether the person had deferred persisted.

Among black and minority ethnic NQSWs, the failure rate fell from 2.71% in 2018-19 to 1% in 2021-22, but over the same period, the rate for white practitioners dropped from 1.11% to 0.28%, meaning they were three times as likely to pass.

And women were more than twice as likely to pass the year in 2021-22 than men (0.36% as against 1.17%), as was the case in 2018-19 (1.39% as against 3.13%).

How the ASYE works

The ASYE year is designed to support NQSWs in England to consolidate learning from their pre-qualifying programmes and ensure they can meet the standards of the knowledge and skills statement for adults’ services or the post-qualifying standards for practitioners in children’s services. It applies to all settings and is open to practitioners up to four years after qualification.

For the children’s programme, employers receive £2,000 per NQSW from the Department for Education, whereas for the adults’ programme payments are worth £1,000-£2,000 per practitioner from the Department of Health and Social Care, with money distributed by Skills for Care.

During the ASYE, NQSWs are expected to carry a 90% caseload, to allow time for learning, and are expected to receive reflective supervision once a week for six weeks, then once a fortnight up to six months and then monthly for the rest of the year.

They are supported by an assessor or supervisor, who assesses their progress over the year. Assessment is based on practice observations, feedback from children or adults supported by the social worker and from other professionals, written reports by the practitioner and critical reflections.

The ASYE is not compulsory for employers of NQSWs, but some employers do use the year to make decisions about social workers’ ongoing employment.

Need for spaces for minority ethnic social workers

Skills for Care runs a dedicated group for ethnic minority social workers (GEMS), whose members have raised issues including dealing with racism from both people who receive support and colleagues, and the negative impact on them of having to adapt their speech, appearance and behaviour to the expectations of others.

The size of the group has grown over time and its members have confirmed the value of having a forum specifically for them, with some highlighting the need for this to continue post-ASYE.

“This indicates that there is still a gap between reality and the need for these NQSWs and social workers to be offered specific support that is geared to their needs in an environment in which they feel safe enough to express and explore their need for support which enables them to grow and develop as qualified social workers,” the report said.

Most NQSWs surveyed for the report agreed or strongly agreed that everyone in their organisation had an equal opportunity to develop (75%) and that leaders were approachable on issues of anti-racist practice (69%). However, because of small sample sizes, these were not broken down by the person’s ethnicity.

More NQSWs reporting additional needs but some fear disclosure

Skills for Care said more NQSWs were reporting additional support needs to their employers. In many cases, organisations were responding appropriately through their policies and procedures and there were good examples of employers supporting neurodivergent social workers, such as those with autism or ADHD.

However, the report added added: “Not all NQSWs feel as though they are having an equitable experience or feel comfortable enough to disclose additional needs to their employer for fear of jeopardising their employment opportunities or their ASYE.”

The workforce development body urged employers to put in place an equity, equality, diversity and inclusion (EEDI) framework for the ASYE, co-produced with graduate social workers, that “makes it clear from the outset what support is available to NQSWs and what the process is for gaining support”.

Workload concerns

The report added that workload was “another area where NQSWs are not receiving an equitable experience”.

Even where there were good organisational policies in place to manage workloads in line with the ASYE framework, NQSWs were often willing to take on a higher-than-recommended caseload due to loyalty to their teams, in the context of high rates of referral to children’s services.

“The strain of taking on additional and more complex cases before they are ready does not support NQSWs to develop deeper learning that will support them within their career and can lead to early burnout,” the report warned.

“It is therefore crucial that senior managers are aware of this issue and are proactively instrumental in protecting development time for NQSWs and ensuring caseloads are at the appropriate level.”

Leads, assessors and NQSWs supportive of ASYE

ASYE leads, assessors and NQSWs were generally positive about the year, in response to surveys carried out by Skills for Care, which also included responses from those working in adults’ services.

All leads agreed or strongly agreed that the ASYE improved the practice confidence of NQSWs, while 89% said that they believed it improved outcomes for people receiving services.

Among assessors, 89% agreed that the ASYE improved practice confidence and 82% that it improved outcomes.

While NQSWs surveyed were less positive as a whole, 81% agreed that the ASYE boosted practice confidence, with 73% saying that it improved outcomes.

‘There is more to do’ – directors

In response to the annual report, the Association of Directors of Children’s Services (ADCS) said it was positive that there were record numbers of enrolments in the 2023-24 ASYE and the failure rate has fallen over time.

Nicola Curley, chair of the ADCS’s workforce policy committee, added: “At a time when need in our communities is growing, so too is our need for more people to choose social work as a career and to stay in the profession. Further work is needed to understand why some groups are more likely to be unsuccessful in completing the ASYE than their peers. This includes people from Black and global majority communities, males and those who have deferred their ASYE.

“The report highlights how equity, equality, diversity and inclusion (EEDI) is being strongly promoted by employers and that more newly qualified social workers are comfortable disclosing any additional support needs they have during their ASYE, which can only be a good thing. However, the report also acknowledges that there is more to do here and in other areas, such as ensuring that caseloads are manageable, individuals have appropriate protected time for development and feel able to raise any concerns they may have with their managers.

“As employers, we are committed to doing all we can to support our staff across all stages of the workforce, from newly qualified social workers on their ASYE through to senior leadership. We cannot make a difference to the children and families we work with without a well supported social work workforce.”

Early career framework question marks

The report comes with the previous government having initiated work to replace the children’s ASYE with a five-year early career framework, under its Stable Homes, Built on Love children’s social care reform programme.

Last year, the Department for Education (DfE) selected eight organisations as early adopters to help develop the ECF, before appealing for a second cohort of employers to come forward in March this year.

No announcement was made on the second cohort before the election and the new Labour government has been silent so far on which aspects of the Stable Homes, Built on Love reform programme it will and will not take forward.

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Is concerning. Not sure if AYSE scheme is fit for purpose. I think year too long. When I qualified moins ago, day 3, I was removing 2 children after 5, only worker in office. Then court with TM supporting through process. Good experience.

When I qualified you went in as a Level 2, to get to level 3 you were assessed against set criteria ie write court report/attend court/ maintained relationship etc etc, some folk were held back for a further 6 months to achieve, one woman was given her level 3 because she’d been on maternity leave for 9 or the 12 post qualifying months- supported by the Union- grossly unfair and you could tell the deference in practice . No social work trainers stick to the criteria to meet goals and it begins in college – because, no one wants to do the job so anyone can …….

This happens on ASYE years too, believe me. The baptism of fire approach might work for some but not all. 90% caseload is still a large caseload if the rest of the service has an extremely high caseload.

I think we owe more to the families and children we support than sending a very recently qualified and inexperienced person to deal with a crisis.

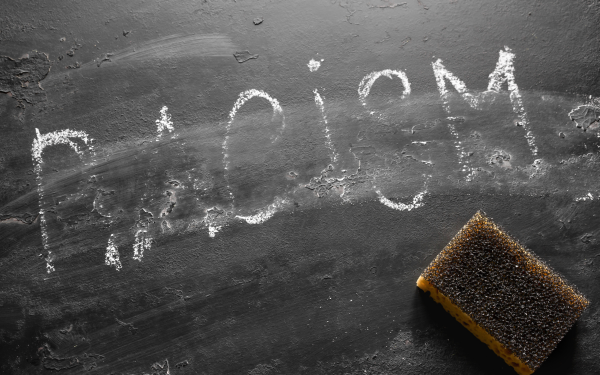

There appears to be more and more evidence that social work has a significant problem with institutional racism and what appears to be unconscious bias. Higher numbers of black and ethnic minority workers subject disciplinary action now issues with ASYE completion. The profession seriously needs to look at it’s self and tackle inequality within.

A key problem with the ASYE is that we do not practice what we preach.. one size does not fit all. I’ve had ASYEs under the apprenticeship program and others who have qualified under a different route. Not only have their abilities been different but so have their learning experiences. So when it comes to doing the ASYE they have a variety of skills. There will be those who are already practicing at main grade level and beyond, sometimes more skilled than fully qualified. Then there are others where I feel they passed their qualifications because the journey to fail a student so they have more time to develop is harder than not doing so. We do a tough job. I haven’t had a single final year student that I’m prepared to sign off unless they can manage a case load of at least 15 and yet this has been with much argument with the universities who say it is too much and 8 should be the maximum. But that’s still a massive jump when someone is an ASYE with only a 10% reduction and those figures don’t account for weighting of complexity. I see it is my role with a student to build them up during their placement so they are managing that 15 of mixed complexity with confidence. Likewise with ASYEs there will be those that need the recommended cap or less and others who do not. Despite the difference a key Factor is making sure they are and feel supported in whatever they are doing to ensure they are confident and their practice is appropriate and safe for all involved.

I feel someone not passing their ASYE is more of a reflection upon the employer than the individual. It’s time the profession, employers and educators got real about the challenges of becoming, let alone, being a social worker (I can speak on childrens SW over the last decade)….Truly it seems like one of, if not, the most difficult jobs a person can do! The high staff turnover, sick rate and mixed outcomes for children and families evidence this. Working specifically with the highest need families in society, brings with it naturally, the highest level of risks and complexities. To expect people to manage this after coming out of university is unrealistic, especially as the caseload expectations for social workers are unrealistic anyway. Its setting people upto fail, or to work themselves to burnout. At my most cynical, Marx’s theory of the ‘Expendable Army of Labour”, seems apt to describe what is happening here.

Age disparity is still at large, once a NQSW is above 50 years, it is very likely to experience age discrimination to get into ASYE role. This is happening in all local councils and it needs to be addressed. It was with great passion that I chose social work as a my future career. However, it is with deep regret that I have found myself unable to proceed further due to my age. This is very real and happening on daily basis. I do not know where to go from here. Despite my strong desire to embark on this career, this is message that I am getting. Out of all the applications submitted, just few invited for an interview and once I provided my identity with my date of birth, that would become the end of it. I am fit and healthy with no health issues. This has greatly affect my self esteem. They should not be judging the book by its cover but the content of it. I hope this be addressed for future generations.