Councils are often failing to protect the caseloads of newly qualified social workers, with some holding dozens of cases and being allocated complex investigations and legal work contrary to local authority policies, a Community Care investigation has found.

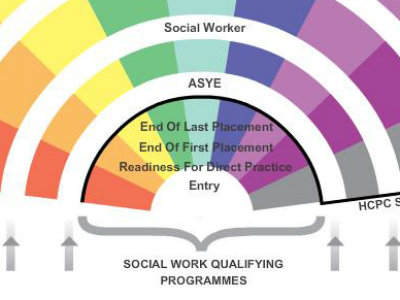

Responses to a Freedom of Information request show that almost all councils have an assessed and supported year in employment (ASYE) for newly qualified social workers, and claim to offer a protected caseload and additional support.

However, actual maximum caseloads range from 10 to 38 cases in children’s and from six to 101 in adults’ services. These figures reflect the highest caseload held by any one ASYE candidate in a council at the time of responding, though authorities have sought to explain these levels (see below).

Differing levels of support

In an online survey, social workers currently undertaking, or who had recently completed, their ASYE programme reported differing levels of support, but many said the reality did not match up to what they had been promised ahead of starting the programme.

A social worker in the north of England who had completed her ASYE told Community Care she had been promised a caseload protected at a maximum of 22 cases, but at no point during her ASYE year was her caseload that low.

“Less than three months into the job my caseload was over 35, partly due to staff turnover, sickness and pressure on the teams in the authority because of a bad Ofsted inspection.

“There was a rule that ASYEs shouldn’t be doing section 47 investigations (where a child is considered to be at risk of significant harm) but this was only stuck to depending on staff availability. There were far too many times during my first six months that I felt out of my depth and unsupported with complex cases that shouldn’t have been allocated to an NQSW,” she said.

“Looking back now, I can see I was experiencing anxiety and work was very much spilling over into my personal life. Late night and weekend working led to weight loss, tiredness and irritability with a constant underlying feeling of panic. I always had butterflies in my stomach.”

A case study in partnership with Central Bedfordshire

Central Bedfordshire’s ASYE programme, part of our social work academy, has had a significant impact on the recruitment and retention of children’s social workers in the council since it launched in June 2014.

Social worker vacancy rates are 50% down on 12 months ago and those involved in the programme cite manageable, monitored caseloads, levels of support, and very importantly, a culture of learning within children’s services as key to its success. Instead of a one year programme, we view it as a five to six year process based on teaching partnership principles.

We work with universities and neighbouring authorities to guide students through from study and placement into becoming a fully qualified social worker. The success of the ASYE programme can be in part attributed to the following key elements:

1. Senior Management Commitment

There has been significant support for the programme from senior management, who participate in recruitment to the programme and closely monitor its effectiveness. The assistant director meets all ASYEs as part of his role and we have very good links with HR around the preparation and implementation of a workforce recruitment and retention plan.

2. Outreach, information, advice and guidance

We have an information, advice and guidance service provided by the academy that directs those Central Bedfordshire residents interested in social work careers (or any other jobs in children’s services) to appropriate information, job vacancies and qualifications. We work with students pre-ASYE on preparation for interviews and visit local universities to run sessions.

4. Focus on recruitment

All newly qualified social workers wishing to apply for the ASYE programme undergo a stringent recruitment process including on-line testing, a full day assessment centre, plus a panel interview with a head of service, team manager, and experienced stage 2 practice educator.

5. Service User Involvement

The Children in Care Council participate in the programme as representatives of service users. They are not only involved in recruitment, but also deliver training to those on the ASYE and evaluate the ASYE programme.

6. Caseload Management

Caseloads in each service area for the ASYE programme have been agreed with the senior management team and those numbers are noted on the ASYE agreement. The ASYE assessor (who is employed and reports to the academy management) monitors caseloads against these numbers, and there is an escalation policy for caseload issues or any other difficulties.

In total, 40% of the 208 social workers responding to Community Care’s survey said their caseload was not protected or capped during their ASYE.

Less than 40% said they had always been given tasks appropriate to their level of knowledge and experience, while 79% had been the primary case holder of either child protection cases, cases going to court, mental capacity assessments or cases involving adult safeguarding concerns.

While 95% said their supervision involved case management, a much lower 55% said it had a reflective element and 52% said they discussed their learning and development during supervision.

The responses from 37 adults’ departments and 41 children’s departments to a Freedom of Information request gave a breakdown of how many cases were held by each of their ASYE candidates on 2 October 2015.

The responses represented the caseloads of a range of candidates at different stages in their ASYE programme, so some variation is to be expected, but the huge variation in the highest caseload held in each council shows some parts of the country are protecting their newly qualified social workers’ caseloads far more than others.

Adults’ services

The average highest caseload held by an ASYE across adults’ services responding to the request was 31. But North Yorkshire, Essex and North Somerset had ASYE candidates holding caseloads of 101, 58 and 55 respectively.

A North Yorkshire council spokesperson said the 101 figure may be inflated as it was difficult to differentiate between active cases and those that had just not been closed yet:

“The figures are based on the caseloads that were last open to an individual social worker but this does not mean they are currently active cases.

“We have re-looked in some depth at the two highest caseloads we have recorded for an individual social worker – 101 and 89 – and have reduced these figures down to 54 and 57 respectively.”

An Essex council spokesperson, said: “We are aware of the range in number of cases held by our newly qualified social workers, and understand there will be short periods where individual caseloads may be high. It should be noted that any individual numbers reported are ephemeral, and normally change week to week, or even daily. As such we do not report or rely on these numbers in isolation.

“The number of cases on the system does not accurately reflect the active number of cases the assessed year in employment programme was working on as some of these cases are to be closed.

“We view support for newly qualified social workers on the ASYE as essential and put in place any actions required to ensure staff have a caseload reflecting their skills and experience.”

Children’s social care

The average highest caseload held by an ASYE across children’s services responding to the request was 25. In St Helens, Shropshire and Hull, an ASYE candidate held 38, 36 and 35 cases respectively.

A spokesman from St Helens council said that though 38 case was above the council’s average ASYE caseload of 24, it consisted of less complex child in need cases being co-worked with a family intervention worker. He emphasised a recent Ofsted inspection had praised the council’s support for its ASYE participants.

Shropshire’s cabinet member for children and young people, David Minnery, said: “High caseload numbers at that time were a temporary matter whilst teams have gone through reorganisation. We have been working hard to get caseloads to a more manageable position, and our average caseload for our 9 ASYEs is now 18. The individual who had the highest caseload is now a qualified social worker.”

Most councils responding had a recommended maximum caseload for ASYEs of 80-90% of a full caseload, rather than giving a fixed range. This means the most pressured councils whose qualified social workers held the highest caseloads are able to allocate the most cases to new social workers while staying within their own guidelines.

The PCF which sets out what is expected of social workers at all levels has been transferred to BASW but is not mentioned in discussions around accreditation

Social work academic Brigid Featherstone said there was wide variation in how the ASYE was being implemented.

“It’s not a consistent picture but it’s fair to say for many people the assessed and supported year feels more about assessment and less about support,” she said.

Percentage guidelines

Featherstone said the use of a percentage guideline for caseloads was problematic.

“I know it would be difficult to have a fixed number of cases considered to be acceptable but I think it would be really helpful to lay down some maximum guidelines.

“There has been reluctance on a national level to do this and I think it is a missed opportunity.

“Some good local authorities have set a fixed range that is an acceptable caseload and if they can do it, why can’t we do it as a general rule of thumb at a national level?”

The Association of Directors of Children’s Services’ workforce development lead, Rachael Wardell, said that while the higher figures returned by councils were concerning, caseloads were not a “numbers game”.

“Social care cases vary in their complexity, and so it is difficult to draw useful comparisons when looking at caseloads by number. A range of factors are taken into consideration when allocating cases to workers including complexity, risk and years of experience.”

But, she added, as demand for services continues to grow it is vital that social workers are given appropriate supervision, including support, guidance and training in order to ensure their caseloads are appropriate and they can manage them well.

Ticking boxes

One social worker told Community Care their ASYE experience so far felt more like ticking boxes than actually supporting their development as a professional.

I’ve been repeatedly told I have a protected caseload, but no one is clear what an average caseload is, so it’s impossible to work out what 80% of that should be.

“I suspect cases have been given to me at random and none of my seniors have any idea whether they are complex cases or not.”

Others described it as a paper exercise and some went as far as to call it an obstacle to their day-to-day work.

One said: “The ASYE is an excellent idea but unfortunately it has become an onerous task in itself on top of a complex caseload. I worked well into the early hours to get pieces finished, not due to poor time management but the realities of surviving the job.

“Newly qualified social workers are largely left to learn on the job without sufficient access to experienced practitioners.”

On the other hand, some said it was difficult but rewarding and necessary to be ready for practice.

“Overall it has been positive. Without it, I don’t feel I would have had the increased supervision and opportunities to reflect that I have had,” an ASYE participant told Community Care.

But another respondent, who had a positive experience, acknowledged this was not the case across the board: “I had a very good supervisor who protected my caseload and made sure the work was appropriate for me. However, other ASYEs in my organisation did not experience this and had several changes of manager, so felt unsupported.”

I received a lot of support and guidance, and benefitted from weekly ASYE learning sessions.”

The ASYE was one of the recommendations made by the Social Work Task Force in 2009, in the aftermath of the death of baby Peter Connelly and accompanying media storm.

It was designed to help those wanting to specialise their practice and was supposed to be a mandatory condition of registration, but the government decided against making it so.

Developments in accreditation

Recent developments around social work accreditation, however, have raised questions about how the ASYE will co-exist with the new system, or whether it is to be replaced.

Mandy Nightingale leads the children and families principal social worker network, and has been heavily involved in the development of the new accreditation system. But she does not know how the ASYE will fit into this new system.

“My assumption is the ASYE will be a requirement for accreditation. A local authority has to endorse a social worker to go through to be assessed for the approved child and family practitioner status, and logically it makes sense that ASYE will be the first step in gaining this endorsement.

“There needs to be communication about how it is going to work. I agree with the principles of accreditation and of the ASYE. My concerns about implementation are that it will be rushed and there will be a lack of communication from central government about what the expectations are on local authorities.”

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

This has always been the case sadly. It always will be too. ASYE unless legally enforced upon local authorities will always be a nice option but not something that is going to be taken seriously.

The same goes for every other facet of personal development for social workers. As the only legal requirement is that a Social Worker is qualified, the rest simply does not matter.

The other stuff is expensive window dressing to make The Government look good, but is never applied. ASYE is a fad, just like the College of Social Work.

Nobody wants talented, intelligent well educated Social Workers. They want cheap ones.

The longer you stay without the skills, the less excuse to give someone a pay rise.

Agreed, although it is nice to see employers being ‘named and shamed’ for a change. I have been banging on about publishing national caseload league tables for ages so I am glad that CC has done something about it. How much publicity this gets is another matter. It is so interesting to read the same excuses coming from employers time after time – unclosed cases, differing complexity etc – which totally ignore the individual stories you have highlighted. Systems of weighted caseload management have been around for DECADES! Employers will not use them because they need to overload staff to meet their performance targets, and national agencies and government collude in this.

…I appreciate the criticism that ASYE is implemented in a patchy way nationally. Despite the very professional and client centred intentions of the Social Work Task Force to provide a framework for graduates to consolidate learning, to practice safely and be supervised appropriately in their first year, employers have found this difficult to respond to. Some authorities have clearly opted in to ASYE with both feet and others are still getting there.

I work with NQSWs and I just want to say that I want talented, well educated Social Workers. I work with talented, well educated Social Workers and as a practice educator and social worker with nearly 20 years experience I appreciate their commitment, enthusiasm, aspiration and struggle to do the right thing with and for the people on their case-loads. Please ask our service users what they want.

ASYE has only been with us since 2012 and real systemic, organisational and cultural change for the Social Work profession will take a while.

Hang in there NQSWs, you are the next experienced Social Workers – we are in this together.