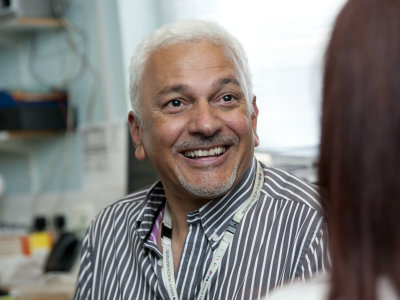

The management challenges facing Eddie Wilde will be familiar to others tasked with managing mental health social workers who are integrated with NHS colleagues in multidisciplinary teams.

Wilde is one of two managers at Lambeth’s forensic community mental health team, part of the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. The team’s other manager, team leader Sam Quartey, is a nurse by background.

The team itself is staffed by ‘care coordinators’ – generic roles filled by a combination of social workers and nursing staff.

This frontline set up is typical of how many mental health teams are coordinated across England, yet the general shift to generic roles has been accompanied by longstanding concerns that social work’s distinct contribution (and that of the other professions) is being diluted and eroded.

The importance of supervision

Improve your supervision

Expert advice on improving your supervision will be available at Community Care’s forthcoming Supporting managers in social work conference, on 17 September in London. Register now for a discounted place.

How does Wilde try to ensure that social workers maintain their sense of professional identity in an environment dominated by the medical professions?

“I think it’s quite unique that we have two managers supervising the team – one from nursing and one from social work. That has allowed us the time to focus on our own professions as well as the work as a whole,” he says.

The set up allows for social workers to get two sets of supervision. They run through cases and the reports that are due for each patient with Quartey, while Wilde provides reflective supervision about social work’s professional role and a space to discuss any issues his social workers are facing.

It’s a vital component of supporting the wellbeing of social workers in a team working with some high-risk and highly complex forensic mental health cases every day, he says.

“It’s focused solely on reflection, development and skills and any knowledge or social work theory they’d like to talk about,” explains Wilde. “I think that’s so important with them being in a multidisciplinary team that they still have an identity. They know that we can just talk about social work and any issues they’re facing.”

“I think that this difference about what is managerial supervision and professional supervision needs to be teased out even more. I think some managers might send back data indicating that ‘supervision has happened’ but in actual fact it might just be a quick run through cases,” he adds.

Getting the social care agenda noticed

There are other management challenges presented by integrated working, Wilde admits. Drawing attention to the social care agenda around things like adult safeguarding or personalisation in the medically dominated world of mental health can be “difficult sometimes”, particularly when a lot of the team’s performance indicators and data is geared towards NHS targets.

“In the past two years there has been a lot more work where both the mental health trust and social services have tried to address this. The issue however is that it doesn’t feel that the information is always filtering down to the frontline,” he says.

When I speak to Wilde’s team they raise various positives and drawbacks of integrated working. Some say it has given them a greater appreciation of medics’ roles and vice versa. Others say they have gained a lot of useful knowledge around how different medications impact on service users and the dilemma of working with non-compliance around medication and its consequences.

The drawbacks they highlight are familiar ones that have been voiced by many social workers nationally, most prominently the overriding feeling that they spend a lot of time doing tasks more weighted to the medical end of things – for example, checking and monitoring medication – and less traditional community-based social work.

“There are good parts but the downside for me is that we don’t get a lot of chance to do group work and task-centred work,” one social worker tells me. “So a lot of the social work stuff that we trained to do, that we wanted to do, we don’t really have the time to do it.”

Wilde recognises the concerns and admits that, particularly at a time of resource pressures, managing the inevitable tension between social care and health priorities can be “really, really hard” for frontline staff and managers on both sides.

But, having managed in the integrated team for the last decade, he also tries to remember that progress can be, and has been, made.

“I know what it can be like. It was horrendous for both sides when we first integrated. It was really a stand-off with one half saying ‘this is health’ and the other side ‘this is social work’,” he recalls. “There were all sorts of issues, even with things like parking. And it was a bit like “that room is yours, this room is ours.”

“So I’ve gone through bits that people who are new to this service wouldn’t believe,” he adds. “We were really the Cinderella part of the service back then. We still are, but that really doesn’t recognise the vast improvements that have also happened over the past 10 or 12 years.”

Andy McNicoll is Community Care’s community editor

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  ‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services

‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services  How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence

How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence  How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families

How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Comments are closed.