8.30am

The team’s phone lines open in 30 minutes. When they do, referrals will start arriving from NHS teams, doctors and police from across Devon, all requesting Mental Health Act assessments for people whose deteriorating mental health could pose a danger to themselves or the public.

Team manager Robert Lewis checks if any referrals have arrived from the out-of-hours services overnight. Unusually, there are none.

It’s welcome news. This has been a busy week. At its worst, one AMHP got home at 3am, partly due to problems finding a bed for a patient who needed urgent hospital care.

Bed pressures are an issue across the country and Devon is no exception. The AMHPs say that finding a bed can sometimes take a whole day.

“I worry about the experience of the patients,” says Sandy King, one of the team’s AMHPs. “Going through an assessment and into hospital is distressing enough. If someone has to be detained like that [after long delays] you just think ‘what a start’.”

8.45am

It’s time to talk through “the board” – the whiteboard listing referrals and the status of detained patients, including the hospital they are at.

Bed pressures mean a growing number of patients are being placed out-of-area, often at private hospitals (again, a national issue). The board shows people placed in hospitals in Bath (103 miles away), south London (204 miles) and greater Manchester (239 miles).

“We’ve already got quite a full board and the phones aren’t even on yet,” says Lewis.

9.30am

One case is causing the team concern. An NHS crisis team is requesting an urgent Mental Health Act assessment for Stewart* (not his real name), a man with paranoid schizophrenia whose condition has worsened in recent weeks.

Stewart is refusing to engage with services. He has a history of being violent towards staff and relatives when ill. His family and key worker are worried.

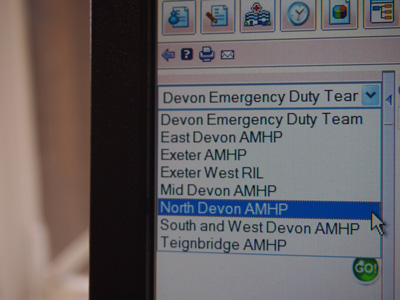

The AMHP team pencils in an assessment for 11.30am. It will be coordinated by Dawn Bevington, the duty AMHP in Stewart’s area today (the team covers five rota areas spanning Devon).

Before they can assess Stewart, Bevington and the team need to line up the services required for a Mental Health Act assessment.

Top of the list is doctors. Every assessment needs a doctor who is approved under section 12 of the Act. It also needs a doctor who has “previous acquaintance” with the patient. One doctor can fulfil both requirements, but often two are needed.

All NHS consultant psychiatrists have section 12 approval so are on-hand for ward-based assessments, but the AMHPs often have to turn to independent doctors for urgent community assessments.

Stewart’s history of aggression and the fact he is refusing to open the door to services, means the AMHPs have also been to court to obtain a warrant giving the police power to force entry to Stewart’s flat if needed.

Having the warrant alone isn’t enough. The police need to be around to enforce it, so the team need to make sure they can attend the assessment too.

Finally, the risky nature of this case means the AMHPs also want to line-up a hospital bed, and an ambulance, so there isn’t a delay if Stewart needs to be detained.

The AMHPs ask the crisis team (who have responsibility for finding beds at Devon Partnership NHS Trust) to check bed availability.

9.45am

The crisis team has a beds update. All of the psychiatric intensive care unit (PICU) beds Devon has access to are full, as are the private hospitals they often turn to. As things stand, if Stewart needs detaining there’s nowhere for him to go.

An inpatient ward five minutes’ walk from the AMHP office has a potential bed available but it’s a general acute ward – not geared up for intensive care. Stewart’s history of assaulting staff means that the ward won’t take him until he’s been stabilised at a PICU.

The crisis team is pushing for AMHPs to assess Stewart and worry about a bed later. But Stewart’s previous record of violence means the AMHP team won’t leave Bevington facing the possibility of being left alone for hours with a distressed patient.

10am

The board is filling up with more referrals. All of the duty AMHPs are busy setting up assessments or out in the field. The time it takes to set up and carry out a Mental Health Act assessment (including paperwork) means AMHPs can normally only complete one or two a day.

“We’re only at 10 o’clock and we’ve already got more than a full quota per AMHP,” says Lewis.

10.15am

Bevington has a problem. The doctor with “previous acquaintance” who best knows Stewart’s case is a locum. He’s currently working in another county and can’t do the assessment. Bevington starts contacting alternatives.

Lewis gets a beds update. There’s a bed empty at a neighbouring trust but it’s not one Devon is contracted to use. The crisis team is trying to negotiate with them to see if Devon can use it as a temporary solution while they look for a PICU bed (it turns out they can’t).

“This isn’t a case of us predicting that Stewart will have to be admitted, it’s about safety for our staff,” says Lewis.

“We’ll step people down and cancel a bed that’s taken a day for us to arrange if the assessment finds that detention isn’t appropriate.”

In the meantime, a different referral is wiped off the board. Doctors have decided there’s no need for a Mental Health Act assessment after all.

10.37am

Success. Bevington has secured two doctors for Stewart’s assessment at 11.30am. She’s about to call the police to line-up their attendance when she notices a problem: the warrant allowing them to force entry has the wrong address.

It turns out an NHS IT system hasn’t updated Stewart’s address. The AMHPs had no way of knowing. The error invalidates the warrant. They are going to have to apply for a fresh one at the magistrates court.

The magistrate can see Bevington at midday. Stewart’s assessment is postponed until 2pm.

Alexis Moran, one of the team’s AMHPs, offers to re-write the warrant application for Bevington to free her up to reschedule other elements of the assessment. Bevington phones the two doctors she’s lined up for the assessment. Both can make the new time.

“We just need to rearrange the police now and getting an ambulance will be tricky. Plus, there’s the ongoing bed issue. But one step at a time,” says Bevington.

10.45am

The crisis team think they’ve found a PICU bed that can take Stewart if needed. There are only two problems: the bed can’t be confirmed until 1pm and it’s at a private hospital in south London, over 200 miles away.

11am

The 2pm assessment is on if Bevington and the team can book an ambulance. Lewis leaves messages with three private ambulance companies.

NHS ambulances can often be lined up for scheduled assessments. But for urgent cases, like Stewart’s, private services are often used, particularly when a patient may need to be transported miles out of area (NHS services are reluctant to have crews out of 999 action for so long, says Lewis).

11.20am

Bad news. As duty AMHP, Bevington wants to get in touch with Stewart’s Nearest Relative but is told he won’t be available until 2.15pm at the earliest. Nearest Relative is a specific role defined in the Mental Health Act that gives the relative some powers in relation to detention, discharge and actions being proposed by professionals.

11.45am

Bevington arrives at the magistrates court. After some questions, the magistrates agree a warrant is necessary and approve it. If Stewart refuses to open the door for his assessment, the police will now legally be able to force entry.

12.15pm

One of the ambulance firms calls. They have a vehicle sitting in a repair shop, but they’re hoping they can get it up and running in time to attend Stewart’s assessment.

“Their patience is being tested because of the beds issue too. We book them for assessment, they refuse work in the meantime, then we tell them the bed has gone and we have to call the whole thing off,” says Lewis.

Bevington starts gathering the paperwork she needs for Stewart’s assessment. Lewis is also on the phone. Another two referrals have come in.

“This is starting to become a busy day,” says Lewis.

1pm

Bad news. With less than an hour to go until Stewart’s assessment one of the doctors has had to pull out as their child is ill. The assessment can’t go ahead unless the team can find a replacement.

I ask Lewis how Bevington is likely to feel about the last-minute problem given all the hard work that’s gone into coordinating the assessment. “If I was her, I’d feel like crying,” he admits.

1.20pm

Better news. Bevington has managed to get a replacement doctor for Stewart’s assessment.

I pop over to the crisis team’s office to talk to Mark Spraggs, who is still trying to secure a bed for Stewart.

“That’s all I have done so far today. Think of the things I’ve missed – I haven’t been able to do any home visits for example,” he says.

1.45pm

Bevington is about to set off for Stewart’s assessment. Her phone rings. The crisis team have had confirmation on the bed in south London. If Stewart needs to be detained, at least she can minimise his distress by getting him to a hospital quickly.

2pm

Bevington meets the doctors next to Stewart’s flat. They discuss the background to the case. Bevington’s phone rings – it’s Stewart’s Nearest Relative. The relative believes Stewart needs hospital care as his condition has worsened so much recently.

2.15pm

Two police officers arrive for the assessment. They explain that their job is to “keep everyone safe” – Stewart, Bevington, the doctors and neighbours.

They ask some questions. Why does Bevington feel forced entry could be necessary? How likely is it that Stewart will get violent? Could he have access to any knives or other weapons? Are there exits to the building that need covered?

One officer is anxious that the earliest the ambulance can arrive is 3pm. If a situation arises where he has to restrain Stewart, he doesn’t want to be doing it any longer than necessary.

Later I ask Bevington if she gets at all scared on assessments?

“I’m much more frightened of the bureaucracy to be honest,” she says. “You’ve got to remember people who need assessed are going through their personal hell. It must be scary when we turn up, sometimes with the police. I always try to make it as calm a process as possible.”

2.30pm

The team go to Stewart’s flat. Even at this stage, all of the work coordinating doctors, police, ambulance, beds, could be for nothing if Stewart isn’t at home.

Stewart’s refusal to engage with services means that the assessment had to be unannounced. If they’d phoned in advance, he may have fled.

4.45pm

The ambulance pulls away. Stewart is inside and the crew set off on the three hour drive to the London hospital. The recommendation from the assessment was that Stewart should be detained.

Forced entry wasn’t needed. Stewart was calm during the assessment and said he felt he needed hospital care.

Red tape caused issues. When Bevington told the hospital Stewart would need the bed she was told the bed hadn’t been confirmed. Apparently a fax hadn’t arrived from one of the NHS trust’s departments.

The hospital also demanded Bevington fax them the papers from Stewart’s completed assessment. With no access to a fax machine in Stewart’s flat (“do they think we carry them on us?”) Bevington ran to a nearby office to send the fax from there. The bed, eventually, was confirmed.

I ask Bevington how she felt when it looked like the bed had fallen through?

“I worried for the guy. He was ready to go and delays could have made him more distressed. The police were also wanting to leave. To be honest, I was also thinking – am I going to get home in time to put my kids to bed,” she says.

5pm

We get back to the AMHP office. Today, the team has handled 12 different pieces of work across Devon, including nine Mental Health Act assessments. Bevington heads off to write-up her report of Stewart’s assessment. It is likely to take at least two hours.

Other AMHPs are still out in the field. One is stuck in a police custody suite trying to secure a bed for a patient. Another is having problems as a section 12 doctor is delayed getting to an assessment (the AMHP ends up finishing after 8.30pm).

Lewis says today’s workload has been “a bit more than average”.

“The big thing for me is that today showed our safety in numbers,” he says. “We dealt with the problems together and could pitch in together. Before we redesigned the team, we’d have all been isolated and be taking on these things on our own.”

The day’s final task is to send a handover email to Devon’s Emergency Duty Team – the service providing out-of-hours social services.

Lewis types the email: “Stupidly busy today, nothing to handover.” He hits send and shuts down his computer. It all starts again at 8.30am tomorrow.

*Note some names have been changed to protect anonymity

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Comments are closed.