By Tony Stanley and Lisa Gunstone

‘Radicalisation risk’ is an emerging practice issue confronting social workers, families, communities and local authorities. Alongside child sexual exploitation and children reported ‘missing’ from home and care, these new areas of social work are mostly issues external to parental care and the family home, so we need fresh ideas to inform our social work offer.

We think, however, that ‘radicalisation risk’ is a misleading term – and a simplistic use of language. It writes in particular narratives about vulnerability, risk, and blame while erasing others. Simplistic language will encourage unsophisticated options for practice.

If we define this in traditional ‘child abuse’ terms, we have a ready-made victim and ready-made perpetrator, or (and more likely) a set of scary unknowns, that we quickly set out to eliminate to resolve. But what happens to our social work relationships when we are in a hurry? Working with uncertainty is a practice reality, while not always a comfortable place; are we too keen to get to ‘safe certainty’?

‘Violent extremism’

Tony Stanley will talk more about the use of family group conferences in cases of radicalisation at Community Care Live Birmingham, which takes place from 10-11 May.He will be speaking in a session on 10 May at 11.30am alongside Jo Fisher, service director for prevention and early intervention at Luton Council, and Adele Penfold, Luton’s operational lead for safeguarding and radicalisation.For more information about the conference, click here.

For more in-depth information about social work practice in cases of suspected extremism, visit Inform Children’s knowledge and practice hub.

The term ‘violent extremism’ is closer to what we think we need to intervene in. Social workers are not trained to determine radicalising actions or behaviours. The cases where adults have shown abhorrent violent video imagery to children are by far the minority of cases. Mostly we are dealing with young people who seek or desire links to the self-defined caliphate in Syria, or families who desire a life under the same.

Some will argue for the protection of these children, in terms of removal, from such poor adult decision making. Others argue that we have sufficient state controls in place and a national Prevent policy to offer help to these families. For some Muslim families this will feel like an overly zealous state apparatus.

So, how can social workers offer a humane and more helpful approach to this complicated area of practice? How can we avoid the laziness of language and simplistic responses like child rescue?

Families as a resource

For many families, the offer of Prevent has been taken up and found helpful. Others have declined this offer, and a referral to children’s social care follows. We need a practice offer in the middle. The family system needs to be held in mind as a resource. In the name of help we too often remove a child from what we define as an unsafe household.

We find it uncomfortable to work with risk, as risk. Risk aversion dominates – and we are driven/ encouraged to avoid it. Too often families are not helped when this practice dominates.

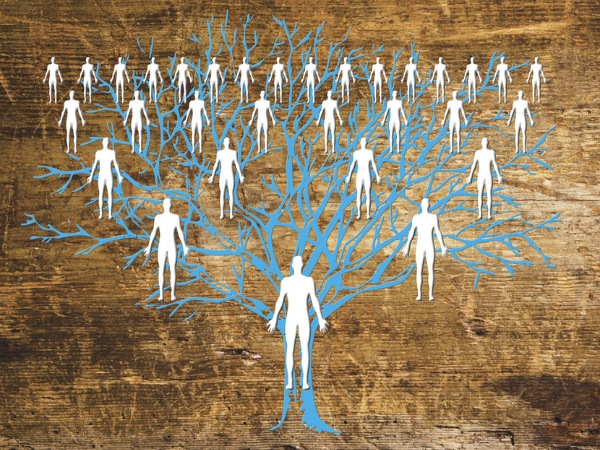

One way to do things differently is to widen the family circle. Not everyone in the family will hold the same views and ideological beliefs.

Ideology is not uniform. It is lazy when we apply broad brushstrokes to family systems and deny them voice and activity to participate and help.

Where are the aunts, grandparents, friends and neighbours?

We need a social work system where social and family networks are invited in, and social methods of help drive our work – and the family group conference (FGC) is a good example. Families hold rights to be involved in the decision making about their children and vulnerable adult members. The FGC offers a restorative intervention approach for working with risk.

This is a family-focused restorative model where the resources within and around the family are drawn on to harness safety and strengths to help children and families. The FGC provides a facilitated space for families to locate solutions and options to help keep their young people and children to be safer. We need to trust families and invite them to be partners in the work.

Preventing family breakdown

The evidence (for example, Ivec, 2013) shows that FGCs work to widen the circle of involvement and then bring challenge to behaviours inside family systems. Further, it is more cost effective and socially just to commit resources to prevent family breakdown rather than to respond to problems later.

Commentators such as Kate Morris and Marie Connolly argue it is effective in early help, with success in complex cases noted because families get to see the urgency. Most families, when consulted about their experiences of the approach, tell researchers they wish it had been offered earlier. The FGC provides a rights-based intervention method without the need for definitive or conclusive assessments of risk.

Birmingham Council is offering the FGC as an approach to intervening in cases where the risk of radicalisation or extremism is identified and the Prevent offer declined. This is a way to bring family networks together to hear the concerns and plan for next steps. The FGC has a built-in private time for families, free from the state’s eyes and ears. We need to give families the power and the opportunity to help themselves.

Major rethink about ‘helping’

The debate about the efficacy of our existing child welfare system is alive and well. Some will argue for the current system – preferring a professionally driven system where trust is optional. However, others argue it is time for a major rethink about what we are doing in the name of statutory social work ‘helping’.

The FGC offers a humane and socially just solution to this emerging and complicated area of social work. Nevertheless, it relies on social workers and managers believing that families are worth doing business with.

Dr Tony Stanley is chief social worker at Birmingham Council, and Lisa Gunstone is its family group conference manager

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Comments are closed.