by Paul Bywaters

The Child Welfare Inequalities Project, funded by the Nuffield Foundation, has established that children’s chances of being looked after or on a child protection plan in the UK vary greatly and that family socio-economic resources, ethnicity and local authority funding are three key factors.

This evidence of inequalities in children’s social care has fed into a wider debate about the case for more funding to avert a crisis of demand. But questions need to asked about the pattern of services as well as the scale of expenditure.

In England, at any rate, austerity policies have led to a radical change in provision with early intervention and family support taking a big hit since 2010, especially in more disadvantaged local authorities, as child protection investigation and looked after children numbers continue to climb.

Large inequalities

Yet the latest CWIP findings show that there are very large inequalities between the UK countries in the proportions of children who are looked after in foster or residential care or who are on child protection plans. Although Northern Ireland has a bigger percentage of children living in the most deprived neighbourhoods in the UK, so you would expect the highest rate of children in care, in fact it has the lowest rate (see table 1).

A child in England is 50% more likely to be in foster or residential care; in Wales 75% more likely and in Scotland 130%. These huge differences are after you have excluded the varied proportions of children who are legally ‘looked after’ (CLA) but in practice living with a parent, relative or friend.

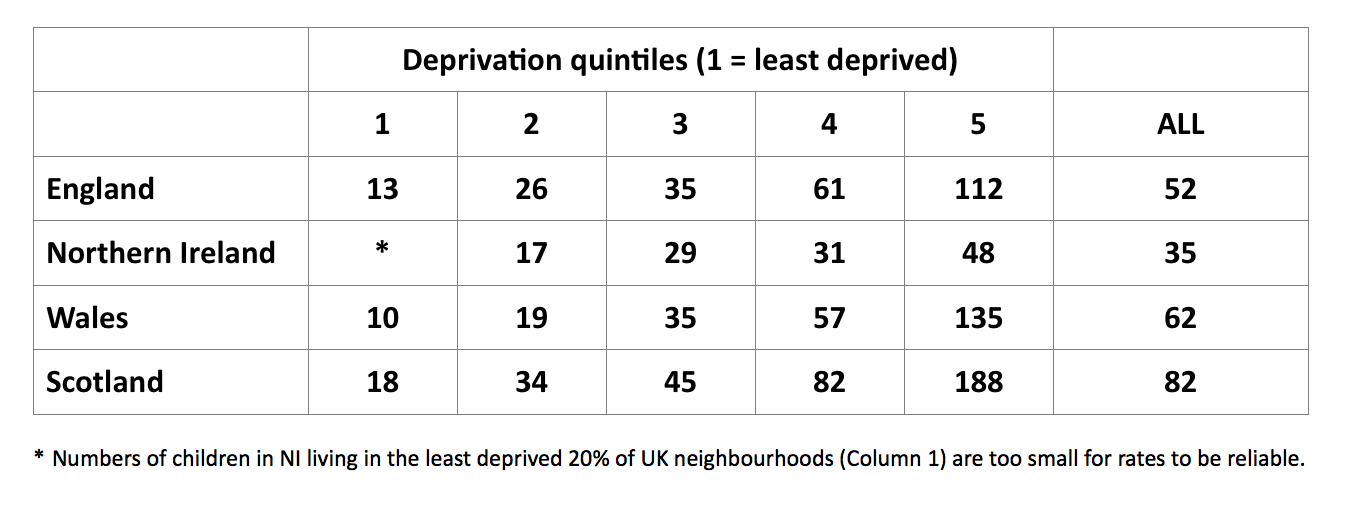

Table 1: Children looked after in foster and residential care, rate per 10,000 children, 2015

When you control for socio-economic disadvantage in the population and compare equally deprived neighbourhoods (columns 1 to 5), the inequalities are even larger. In the most deprived 40% of neighbourhoods, where almost 80% of looked after children come from, CLA rates in England are more than double those in Northern Ireland, and Scottish rates over three times higher.

Table 2: Child protection plans or registers, rates per 10,000 children, 2015

Overall child protection (CP) rates appear similar across the countries, except in Scotland where, unlike for CLA, CP rates are much lower than in the other countries (Table 2).

But when you compare equally deprived neighbourhoods a different picture emerges. For example, in Column 5 – the most deprived 20% of neighbourhoods where around half of all children on CP plans or registers lived – the rate in Northern Ireland is only 20% higher than in Scotland but again much lower than in England or Wales.

This also means Scottish children are three times more likely to be in foster or residential care than on the child protection register, but in Northern Ireland are more likely to be on the register than to be in foster or residential care. It is unclear which country is protecting children better by these profoundly different approaches.

System differences

Why are there such inequalities? We don’t yet understand the reasons for these large differences, which do not seem to be the focus of government interest. It is clear that within each country family economic circumstances and ethnicity are the most significant factors, but between the four UK countries other factors must be at work.

There are major differences between the legal system in Scotland, with the unique Children’s Hearing system, and in the rest of the UK. In Northern Ireland services are provided by joint health and social care trusts rather than local authorities. These structures may or may not be influential.

Alternatively, there may be something different about the strengths of families and communities in the four countries, with local solidarity and resistance to state involvement in family life perhaps greatest in Northern Ireland.

Patterns and funding of service provision and professional cultures may also vary – for example, in the balance between family support and permanent child removal – but government-published data makes confident comparisons of expenditure impossible.

Of course, decisions not to remove children can have dire consequences as well. Northern Ireland might be intervening too little, although there is no obvious evidence to support this view. At the very least, it must be right to question how many children should be in care or on other protection measures.

Profoundly important issues

Why do these cross-country inequalities matter? They matter most because they are of profound importance for children and families. Decisions to separate children from their families or keep them together reverberate through the rest of their lives and the lives of their siblings, parents and grandparents.

Partly in response to our findings, Glasgow has embarked on a radical culture change which is already significantly reducing the numbers of children in residential and foster care and rebalancing services towards family support.

But policy makers and professional leaders should be profoundly interested in understanding these inequalities for economic reasons too. We estimate that if other countries had Northern Ireland’s rates, controlling for deprivation, there would be around 40% fewer looked after children in England, 50% fewer in Wales and 60% fewer in Scotland.

In England this equates to around £1.6 billion per year, which could be available to spend on keeping families safe and together, just under 20% of the total children’s services budget.

The research team is now examining whether practice on the front line in Northern Ireland and the family and community context of practice is significantly different from that in the other countries and we hope to report on that around the end of the year.

But these cross country comparisons are bedevilled by inadequate data systems which do not easily transfer across national borders. So it is the four UK governments that need to take a lead.

The status quo in each country should not be taken for granted. All four countries cannot be getting this right when service patterns are so different.

Paul Bywaters is a professor of social work at the University of Huddersfield

- For free essential learning on the key practice and management challenges facing social work and top-quality training on social care law, register now for Community Care Live London, on 25-26 September.

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Oxfordshire County Council

Oxfordshire County Council  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Webinar: building a practice framework with the influence of practitioner voice

Webinar: building a practice framework with the influence of practitioner voice  ‘They don’t have to retell their story’: building long-lasting relationships with children and young people

‘They don’t have to retell their story’: building long-lasting relationships with children and young people  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  How managers are inspiring social workers to progress in their careers

How managers are inspiring social workers to progress in their careers  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters  Unlocking independence: how ASDAN gives care leavers choice and control over their future

Unlocking independence: how ASDAN gives care leavers choice and control over their future

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Comments are closed.