Social workers have been urged to help tackle the impact on Gypsy and Traveller families of increased police powers to evict them from unauthorised camps, brought in this year.

Practitioners from the communities have produced a guide to carrying out welfare enquiries to help social workers and others support families affected by the measures in the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022.

The Gypsy, Roma and Traveller Social Work Association (GRTSWA) said provisions (see tougher eviction powers box) to criminalise residing on land without consent and give the police greater eviction powers risked increasing existing vulnerabilities.

“We believe that the powers in the Police Act will reduce opportunity and create further deprivation for some of the most marginalised and vulnerable groups in Britain,” says the guide, written by GRTSWA member Dan Allen, principal lecturer in social work at Liverpool Hope University, with the support of the association.

‘Children’s vulnerability created by evictions, not parenting’

Among the vulnerabilities faced by Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities are children’s overrepresentation in the social care system, with numbers growing at a disproportionate rate since 2011, according to research published this year by Allen and social worker Victoria Hamnett.

To ensure this issue is not exacerbated, Allison Hulmes, co-chair of the GRTSWA, said the guide puts the focus on the vulnerability created by evictions, not parenting.

“This isn’t about parenting; this is about state intervention into private and family life,” she says. “So social workers need to separate those two things. The state is actually damaging these children, not the family.”

Welfare enquiries ‘not routinely carried out’

Government guidance from 2006 requires councils to carry out welfare enquiries before evictions take place, to identify “pressing needs”, potentially leading to evictions being delayed while these needs are addressed. The police are also required by separate guidance, issued this year, to ensure that welfare enquiries are carried out and councils are involved as soon as possible.

The GRTSWA paper says that councils and the police “do not routinely ask about these matters, or delay enforcement actions until a welfare enquiry has been conducted”.

There is also no existing guidance for carrying out these enquiries, which Allen said has often resulted in miscommunication between the public services involved and inconsistent implementation.

“Most existing forms that could be used to guide and inform a welfare enquiry are not fit for practice, and no good practice guidance exists that could be used to understand how best to co-ordinate a full and accurate welfare enquiry,” the paper adds.

The guide, which is supported by the British Association of Social Workers, is designed to fill this gap, and includes two forms for practitioners carrying out enquiries to use. The first is designed to collect information on how the eviction would impact on family life and, should this unearth significant welfare considerations, the second form would be used to carry out a more detailed assessment.

While designed to be used by a wide range of professionals, Hulmes said social workers were particularly suited to carrying out the more detailed assessment.

‘You’re constantly living in anxiety’

The guide, which was informed by the contribution of four people with experience of eviction, highlights the widespread inequalities Gypsy, Roma and Traveller families face in relation to health, mental health, life expectancy and welfare.

Analysis of the 2011 Census found Gypsy and Traveller families had the lowest proportion of any ethnic group in rating their health as ‘good’ or ‘very good’ – 70%, compared with 81% on average – and the lowest proportion who were economically active (47% compared with a 63% average).

Hulmes said these issues would be exacerbated by an increase in evictions.

Allen described some families “being woken up at two o’clock in the morning by bailiffs banging on the side of their trailers with barking dogs, forcing them to move on”.

“You’re constantly living with the anxiety of waiting for someone to come in and move you on, and not knowing where you’re going to go or whether you are going to be safe,” Hulmes added.

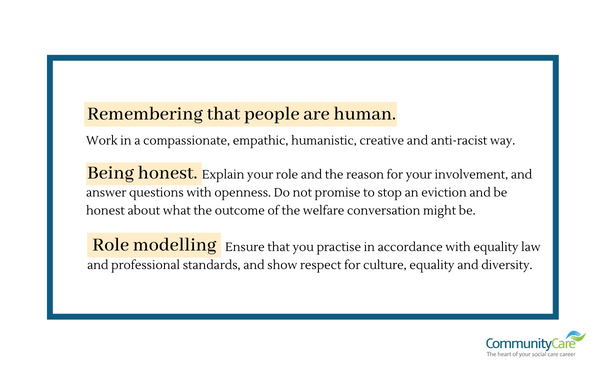

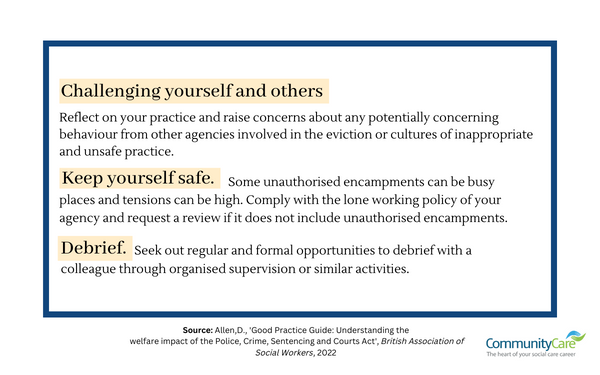

Reflecting this, the guidance places an emphasis on working with families empathetically, compassionately and inclusively.

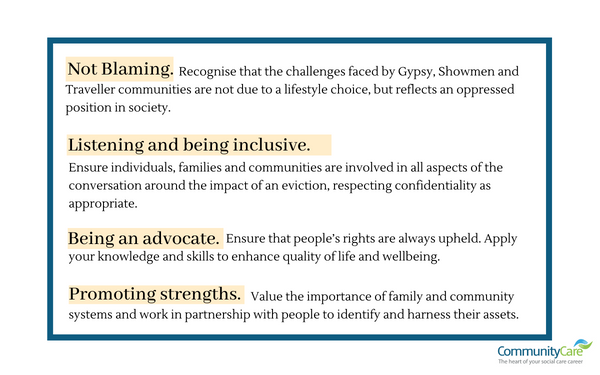

The guide also advocates a “not blaming” approaching, saying that these communities often reside on unauthorised land because of a lack of permitted accommodation.

“We know that families choose to live on the roadside because there is no other alternative,” said Allen.

“They are living somewhere without access to fresh running water, basic amenities, the sorts of things that you and I might take for granted.”

Tougher eviction powers

The Police, Crime and Sentencing Act 2022 amends the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 (CJPO) to:

- Create an offence of residing on land, or intending to, without the consent of the occupier, in or with a vehicle, under a new section 60C of the CJPO. This would apply when the person fails to comply with a request to leave by the occupier as soon as reasonably practicable, and significant damage or disruption has been caused, or would be caused, as a result of their residence. It would also apply if significant distress has been caused by offensive conduct by the person while on the land. A person would also commit the offence on returning to land they had been prohibited from residing on for 12 months.

- Strengthen the police’s existing power to evict people from unauthorised encampments once reasonable steps have been taken by the occupier to ask them to leave, by:

- Widening the criteria for eviction to cases where the person has caused damage, disruption or distress, under section 61 of the CJPO. Previously, evictions could only take place when the person had caused damage to the land or property on it or had used threatening, insulting or abusive words or behaviour towards the occupier or a family member, employee or agent.

- Extending from 3 to 12 months the period for which the person would be prohibited from returning to the land, and widening the definition of land to include highways.

Take-up of guidance

So far, the guidance has been adopted by Wiltshire council and the Welsh Government.

Mark McClelland, Wiltshire’s cabinet member for transport, waste, street scene and flooding, said the authority had been working with a local charity to complete welfare enquiries and was committed to “empowering people to live full and healthy lives, and that includes people that may be temporary residents in our county”.

The GRTSWA has also been working with National Police Chiefs Council lead for Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities Janette McCormick, to spread knowledge of the guide among the police.

McCormick said the police had a responsibility to uphold the law in a way that took into account individual and specific needs.

“It is widely recognised that Gypsy, Roma and Travellers are some of the most marginalised in society and can be subject of significant prejudice,” she added.

“How we police has a significant impact on their trust and confidence in us, and that is the same across all public services.”

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Comments are closed.