Do you like reading books about social work or by social workers in your spare time?

- No, I want to switch off from the job (36%, 316 Votes)

- Yes, that's what I'm into (34%, 299 Votes)

- It depends on the book (30%, 266 Votes)

Total Voters: 881

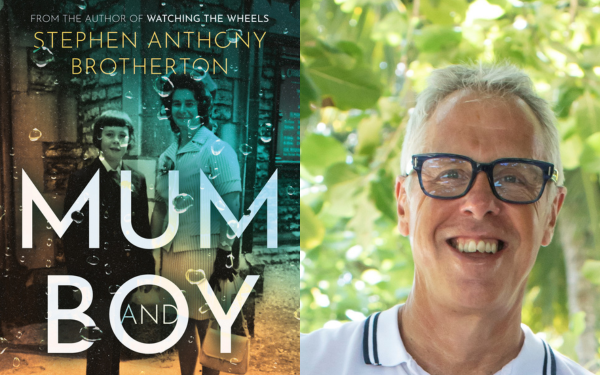

Mum and Boy by Stephen Anthony Brotherton is a quick but powerful read that explores the mother-son dynamic through the gripping perspectives of four teenage boys.

Stephen, who has been a social worker for nearly 30 years and has an interest in the complexity of human nature, drew me in immediately with the first of these short stories, entitled ‘Afterlife’.

In this short story, we meet Jake, who suffers physical and mental cruelty at the hands of his father and sister. He only finds benevolence from his mother who showers him with love and defends him when no one else will.

But there is a twist to Jake’s story where we find him mysteriously buried in a coffin, teetering between death and life, and it is not immediately unclear what got him there.

These open-ended and philosophical endings feature in subsequent stories, forcing the reader to reflect on the impact that these unbreakable mother-son bonds have on these young boys.

Adultification among book’s themes

The book touches on suicide, mental health and the Oedipus complex and also explores the adultification of youngsters who may feel pressure to grow up quickly to care for a parent.

Twelve-year-old Charlie highlights this in ‘Oedipus Revisited’ when he announces that he has proposed to his mother and she has accepted.

The pair have lived without an adult male figure in their lives for years, and this is played out with Charlie assuming the role of ‘husband’ to his mother. But as the story unfolds, we see the devastating impact this bond has on their relationship.

Although each of the four stories appear unconnected, there are golden threads that tie them all together.

Each boy develops coping strategies to deal with their emotional and physical trauma. These coping mechanisms range from creating fantasies to employing breathing strategies to escape their living nightmares.

It was interesting to see how the women in each of the stories were well-defined, while the fathers and other males in the book were quite one-dimensional – adding to the importance placed on the role of the mother figure.

The author’s story

Stephen explains that in his own life, his bond with his mother evolved after the death of his father.

He said: “My interest in the mum and boy relationship comes from my experience of my dad dying when I was seven years old, leaving me with just my mum. She was 43 and never got over his death. I became her little crutch, giving her strength to get out of bed every morning and face the world.

“What happened in my formative years set life-long psychological templates, determining the way I view and interact with the world, especially in relationships. I know these things now, but it’s taken years of internal searching and counselling for me to reach this level of awareness, and it led to me becoming a social worker. I came through, managed to change, adapt, present myself differently, but the impact never goes away. It always exists inside my head.”

These stories paint a vivid picture of what some youngsters have to deal with when navigating the loss of a parent, sibling rivalry and the insecurities of supporting a grieving parent. Add to that mix, the impact of having to navigate these complexities are that cusp of adolescence when most young people are learning to understand themselves, build friendships and just be accepted.

The storytelling in this book is powerful, engaging and thought-provoking, and is likely to resonate with other practitioners who support children and families.

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Comments are closed.