As social work struggles to assert its role in the medically-dominated world of mental health, the situation faced by Audrey Gallier will be all too familiar to many social workers.

“I was a lone social worker in a health team and I was just about feeling like packing it in because my role felt so generic,” she says. “I was doing so many different things within the team, but nothing felt specific to the way I had been trained as a social worker.”

But things have changed for Gallier since her early intervention team, along with 14 other agencies across England, agreed to take part in a two-year pilot study of the Connecting People Intervention (CPI) – an approach to mental health care that has plenty in common with the principles underpinning community social work.

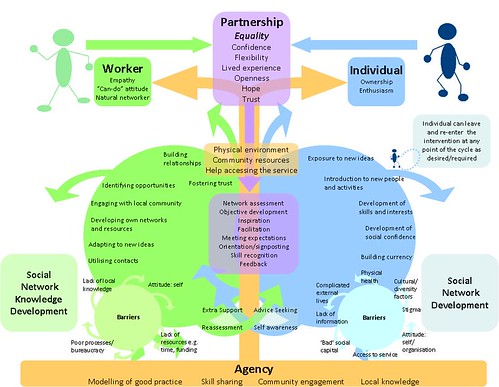

At the core of the model, which is not restricted to social work, is “an equal partnership” between service user and worker. Together they discuss interests and agree a set of desired outcomes for the intervention.

The worker and service user then work together to link in with activities in their community that can support the outcomes and work through any barriers.

The model, which was devised by a multidiscplinary team including social work academic Martin Webber, has allowed Gallier to work with people to meet outcomes that they have shaped together, whether it be through supporting someone to learn to drive or take up a new sport as a means of meeting people.

She has worked with people with communication difficulties to draw up care plans in forms that work for both parties, be it by using cartoonists, or via text messages. It is a break from the perception that care plans are “all about the illness and not about me”, she says.

“The model has really reinvigorated what I do as a social worker. It has interrupted quite a predictable process I used to work with. You know, you’re given a referral, you’re told to act on it and you move through a timed process,” says Gallier.

“With Connecting People, I’ve been able to slow the process down. I’ve been able to think what is the purpose of the intervention, and work far more creatively.”

Much of the model’s approach will be familiar territory to social workers. But having a framework to articulate this way of working in mental health and what social work can do, can help show NHS staff the value of social work beyond its statutory functions.

Rob Goemans, professional social work lead at Lincolnshire Partnership NHS Trust, says piloting the model has helped focus his team on social work’s unique value in mental health. It has also proved useful as a teaching tool and, with mixed success, helped convince others in the medication-focused NHS of the benefits in social models of care.

“Connecting People is a model of what mental health social work should be,” says Goemans.

“We’re not telling social workers that this is all something new. We’re saying a lot of this is what you do already and this is a framework that can help you understand it and help other people to understand it – be it commissioners or everyone in between. It actually gives social workers a much better focus,” he says.

A key plank of the Connecting People model is agency support. But at a time when caseloads are spiralling, budgets are being squeezed, and many mental health social work teams are caught in a power struggle between local authority and NHS priorities, how likely are employers to back a model that could be more resource intensive?

It’s a dilemma recognised by Jason Brandon, a mental health social work lead in Hampshire who is attending a Connecting People workshop in London. He says that the model “chimes with what we should be doing as mental health social workers” but admits he has a “healthy cynicism” over the degree of backing from agencies.

“In principle I don’t see how any agency can refute that it’s a really positive model. But there is an issue of resource – not just financially but the time factor,” Brandon says.

“What I’ve heard today is that once you can get past that, what the study can provide is the evidence base that brings the model integrity and credibility, so that’s really appealing.”

Gallier admits the fact that her manager, a social worker, has been “on board” with the CPI model from the start has made a huge difference, as has the fact she is based in an early intervention team. She acknowledges that some teams’ caseloads in other areas of mental health might prove a barrier to them adopting the CPI approach.

Goemans says that his team had to do a lot of work to convince managers of the benefits of piloting the CPI model, amid concerns over workload.

“When we were struggling to get it agreed, service managers were saying ‘social workers don’t have time for this we’ve got targets to meet with personal budgets’,” he says.

“But other people could see the value in it. Some people said it would be really helpful. Eventually we got a medical director on board which made a big difference.”

The true test of the Connecting People Intervention and its chances of widespread adoption will be its evaluation. One of the factors often identified as contributing to social work’s marginalisation in mental health, is the fact it lags behind the dominant medical profession in terms of its evidence-base.

The CPI pilot study will be completed in March 2014. The team is still keen to hear from social workers interested in the study, while those already involved in the pilots hope the model could bring robust evidence of the social model’s contribution to mental health.

In the meantime, Goemans, and colleagues, are using the model’s community-based approach to shape their day-to-day social work for certain clients.

“When someone is too complex to have their needs met through a personal budget, we’re going to have to put a social worker in to meet those social care needs directly. What do we actually do?,” he asks.

“We all talk about social inclusion and empowering people but these terms alone don’t mean a lot. I’d like to use this model within our protocols and our service planning to try and shape that direct social work delivery.”

Is there a mental health social work issue you feel Community Care should cover? Email community editor Andy McNicoll at andy.mcnicoll@rbi.co.uk

Andy McNicoll is Community Care’s community editor

Assistive technology and dementia: practice tips

Assistive technology and dementia: practice tips  A trauma-informed approach to social work: practice tips

A trauma-informed approach to social work: practice tips

Find out how to develop your emotional resilience with our free downloadable guide

Find out how to develop your emotional resilience with our free downloadable guide  Develop your social work career with Community Care’s Careers and Training Guide

Develop your social work career with Community Care’s Careers and Training Guide  ‘Dear Sajid Javid: please end the inappropriate detention of autistic people and those with learning disabilities’

‘Dear Sajid Javid: please end the inappropriate detention of autistic people and those with learning disabilities’ Ofsted calls for power to scrutinise children’s home groups

Ofsted calls for power to scrutinise children’s home groups Seven in eight commissioners paying below ‘minimum rate for home care’

Seven in eight commissioners paying below ‘minimum rate for home care’

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Comments are closed.