“I always remember the staff who stuck with me during the really difficult times, when I had really lost hope,” says Ian Callaghan, recalling some of the mental health support he’s received over the past 25 years of using services.

“I had a social worker, who I’m still in touch with, who just kept telling me things would get better and that the bad times would pass. She had such positivity for me, whereas it felt some other staff had just written me off. They were still professional with me but you could sense the difference in the quality of interaction. For me, it’s so important to have a professional who sees the glass as half full for people, even when they are at their lowest or most difficult.”

Callaghan, who says he’s had “some great care and some not so good care”, is passionate about improving the experience of people using mental health services. For the past five years, after spending time admitted to a secure mental health unit, he has led several user-led projects designed to promote an approach to care in secure services that is more focused on people’s recovery and outcomes.

Ian Callaghan

As part of this work, this summer Callaghan and colleagues helped set up a national recovery and outcomes conference with NHS England and mental health provider Partnerships in Care. At the event, 120 patients from secure mental health settings used voting pads to tell NHS England how services should be improved. The three areas voters said they wanted to see given highest priority were better community placements (31%), more staff in hospitals (31%) and improved crisis care in the community (23%).

Callaghan says that problems accessing community placements, notably supported accommodation, often hold up people’s recovery by keeping them in hospital longer than they would like. This “bottleneck” can be complicated by the fact that secure services are commissioned and funded nationally by NHS England but community placements are the responsibility of local NHS commissioning groups and local authorities.

“Navigating that system can be a bit of a minefield, particularly if like I was, you have been in a hospital that’s not in your home area but you’re trying to get community support nearer your home. Partly there’s also an issue around some clinical commissioning groups not yet having a full understanding of the needs of someone leaving secure care although I think that is improving,” says Callaghan

“On the staffing side I think the big frustration comes when hospitals are so short staffed they have a high reliance on bank or agency staff and the permanent staff feel incredibly stressed because they are so overworked. When that happens, therapeutic activities get cancelled because there aren’t enough staff and you get problems where you can’t build up sufficiently good relationships with professionals as they’re temporary or really stretched.”

Practice tips

Ian recommended Rethink’s ‘100 ways to support recovery’ as a good resource for practitioners. The guide offers tips on assessments, action planning and supporting people to develop self-management skills.

The time and ability to build those relationships, Callaghan says, is vital to people’s mental health recovery. In recent years he has done a lot of work around users’ experience of care pathways as part of a project called My Shared Pathway. A recurrent theme in this work is that people felt like staff had plenty of case notes about them but many professionals didn’t “properly get to know the person or what, for example, their hobbies are”.

Bringing people’s goals, aspirations and interests to the fore of care planning is the focus of a lot of Callaghan’s current work. He says secure services are getting better at making the process “much more explicit and collaborative” between the user and their care team. The result is care plans that should be more focused on the person’s goals, how they can get there, and how to judge success rather than simply being “huge, long reports that the person is shown and asked to sign”.

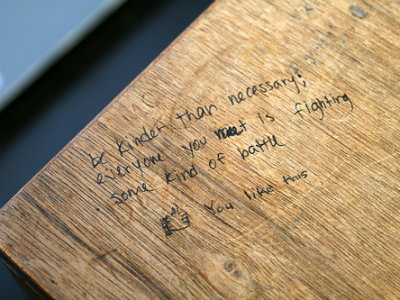

But ultimately, Callaghan says, the foundations of good care often begin with the basic everyday human interactions between staff and users that can be therapeutic in themselves.

“I know these are really difficult circumstances for staff in mental health services just now but spending a few minutes with someone who needs it can just make a huge difference. I remember being in hospital you’d get people who were always too busy and they’d just shut the office door and the other staff that would stand at the door and just listen for a bit, even just a minute or two. That can make a huge difference and hopefully the positive feedback staff get from seeing people value that gives them job satisfaction too,” he says.

“I think things are improving. NHS England is interested in what service users are saying. I think there’s an awareness there and some movement. Things are certainly better than when I was first in secure hospital seven years ago. Now in secure care there’s much more of an effort to sit down with people and work through a care plan together. We know it takes time to do that so staff need the time to do it. If services get this right, it can be a win-win.”

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Comments are closed.