Mr Hughes lives alone on the seventh floor of a tower block in Lambeth. He is a widower who came to the UK from Trinidad in the sixties.

He fell in the stairwell recently, and now he doesn’t leave his flat much. He ventures out to the local Caribbean takeaway twice a week, and lives for the rest of the time on tinned soup and cheese and crackers.

His neighbours have noticed him deteriorating, sometimes failing to recognise them, but no one feels close enough to him to be able to interfere.

Mr Hughes is a case study, outlined by social workers to a group of council employees from various departments, in an overheated town hall in South London: a challenge in how they- as workers in policy, housing, or even just as residents and neighbours themselves—could pull together to prevent a person in their community from reaching crisis point.

‘Crisis point’

But Mr Hughes is not fictional. He’s real, albeit with a made-up moniker. Along with around four million older people like him living alone in the UK, he presents one of the biggest challenges currently facing social workers. Who has the responsibility, and the means, to help him before hospitalisation from a fall or malnutrition escalates him onto the radar of social services?

Hugh Curtis, a social worker in Lambeth’s substance misuse team and a participant in the meeting on co-producing social care, says it is refreshing to hear people who aren’t involved in directly delivering social care taking an interest in what their role might be.

“Over recent times there has been a heightened sense across society that intervention needs to take place. There’s a sense that somebody has to do something—that is, social services have to do something. At times it can feel a bit like we’re under siege.

“It’s very refreshing to hear people saying something other than ‘well social services will have to deal with it’,” Curtis says.

‘Do something’

Curtis is a member of the Social Players, a drama group set up by Lambeth social workers with the aim of educating both social work students and other agencies through role-play about the realities of the profession.

It is the Social Players who have assembled this disparate group of council employees and voluntary sector workers on a grey February morning, to discuss how individuals and professionals other than the social work department can help people like Mr Hughes.

“In a situation like this, having people from all sorts of professional backgrounds is a fresh pair of eyes, and might throw up things we hadn’t thought of,” Curtis says.

“Somebody at my table who was involved in a grassroots community group…said together they would feel more able to knock on the door of [an elderly neighbour] and offer that more informal support.

“That throws up questions for us in social services departments in terms of how we can use that connectedness and harness it to avoid crisis situations and help with prevention.”

Jennifer Orgill, a social worker and practice educator who was involved in setting up the Social Players, says she is keen to highlight to other agencies how interlinked their work is with the work of social workers.

‘Real social work’

Orgill says: “There’s a lot of misinformation and ignorance about what we do and it’s not their [other council workers’] fault.

“We want to say to our colleagues in other agencies—we want to support you, but we need your support. We want to show them real social work.”

She adds that while social workers are constrained by legislation, other agencies like those in the voluntary sector are freer to use more imaginative solutions. The Social Players believe they need to communicate exactly what it is social workers are able to do, so other groups understand where the gaps are they might be able to fill.

“The role-plays are all about capturing the imagination, because the work is getting more and more complex alongside a lack of resources,” Orgill says.

The Players are keen not just to educate other agencies, but to make sure social work students are also fully prepared when they enter this demanding workforce.

‘Gatekeeping’

“In a way, it’s an exercise in gatekeeping for us,” says Nathalie Lee-Francis, a practice educator and Approved Mental Health Practitioner. “We’re teaching new social workers to be guarded about confidentiality while still sharing appropriately where things need to be escalated or they need help and support with a case.”

She adds that educating others in this way has made her more open to learning herself, something Jennifer Orgill agrees with.

“It’s good reflective practice,” Orgill says. “It gives you a space where you can literally reflect on your feet—even while you’re talking, ideas come to you.

“Newly qualified social workers face having to negotiate with managers to make sure their caseloads are right and they get enough supervision. Exploring with students how to communicate some of these things, you realise this is something you should be doing yourself [to manage your own workload].”

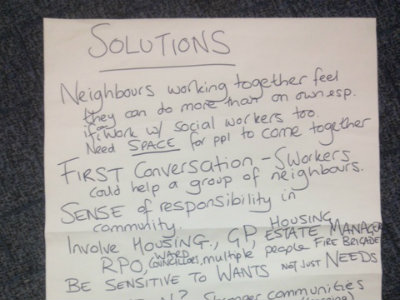

By the end of the council workers’ session, the ideas are flying. Is there a residents’ association on Mr Hughes’ estate that might know of community groups for older people, or be able to link him in with the local Caribbean community? Could he be helped to use a computer so he could combat loneliness by Skypeing his children, who live in Manchester and America respectively? Would he be willing to move to a ground floor flat where he wouldn’t have to contend with seven flights of stairs, and could someone from Housing try to arrange that?

‘Buzzword’

The Social Players are pleased with how it’s gone. It’s got people talking, eager to understand how they can help. But the session has been tinged with a sense of urgency—they are desperate to show others the magnitude of what they have to contend with, not just in older people’s teams but from the growing demand in child protection and mental health too. They need co-production to be more than just a buzzword.

These problems are too great to be dealt with by social workers alone, is the overall message of the morning.

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Brilliant piece of article.