More than 40% of the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (Dols) applications made to local authorities in 2014-15 were not signed off by the end of the financial year, new figures show.

Data published by the Health and Social Care Information Centre reveals that 56,391 (41%) of the 137,540 Dols applications made within 2014-15 had not been signed off by 31 March. Monthly breakdowns show that one in four of the applications received in June had yet to be completed nine months later (see graph).

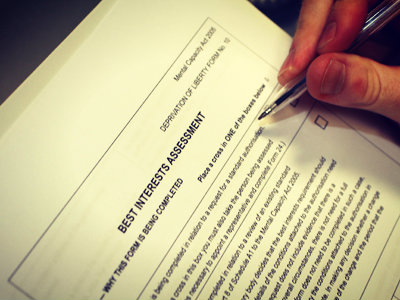

The Dols are used to authorise deprivations of liberty in care homes and hospitals. Councils are required by law to complete Dols applications within either seven days or 21 days of referral, depending on whether the care placement has started or not. The figures showed that among the Dols applications that had been signed off, only 56% were completed within the 21-day time limit.

The figures are the latest evidence of the immense pressure placed on local authority Dols teams by a March 2014 Supreme Court ruling in the cases of P v Cheshire West and Chester Council and P&Q v Surrey County Council (the “Cheshire West” case). The judgment effectively lowered the threshold for what constituted a deprivation of liberty for people who lacked the capacity to consent to their care arrangements, requiring providers to make many more Dols applications.

Evidence of backlogs

Today’s figures show that the ruling triggered a tenfold rise in Dols applications, from 13,700 in 2013-14 to 137,540 in 2014-15. However, in a further sign that local authorities are struggling to keep up with the rising demand, the number of applications completed by councils only rose five times, from 13,040 in 2013-14 to 62,645 in 2014-15.

The lowered threshold introduced by the Supreme Court ruling is also reflected in figures showing that, in the year following the court ruling, 83% of completed Dols applications were granted, up from 59% in 2013-14.

Going forward, all of the 83% completed applications in 2014-15 will require review at least annually on top of councils attempting to clear the remaining backlog and deal with new cases.

There was regional variation in approval rates, with only 61% of Dols applications granted in the South West in 2014-15 compared to 93% in the North East. The Health and Social Care Information Centre said that the variation could reflect the “available resources, local prioritisation approaches and the complexities of each application”.

The fallout from the Cheshire West ruling prompted the government to ask the Law Commission to review the Dols and the wider legal framework around deprivations of liberty. The Law Commission’s proposals for a framework to replace the Dols, and extend to settings outside of care homes and hospitals, is currently out to consultation. If accepted by government they could see legislation to reform deprivation of liberty law introduced in the 2017-18 session of Parliament.

About the ‘Cheshire West’ ruling

The Supreme Court’s judgement in the linked cases of P v Cheshire West and Chester Council and P&Q v Surrey County Council in effect lowered the threshold for what constitutes a deprivation of liberty in care.

The court’s “acid test” said that a person who lacked capacity to consent to their care arrangements was deprived of their liberty, under Article 5 of the European Convention of Human Rights, if:-

- they were under continuous supervision and control;

- they were not free to leave, and;

- their care arrangements were the responsibility of the state.

The ruling rendered irrelevant factors that had been allowed for in the past, such as whether the person objected to their care arrangements.The Supreme Court also made clear that such a deprivation of liberty would apply in a domestic setting, as well as in health or social care placements.

The judgement was welcomed for extending key human rights safeguards to a broader group of vulnerable people. But it meant that, overnight, many people in care homes, hospitals and supported living arrangements suddenly met the threshold to have their care arrangements assessed or reassessed to see if they were deprived of their liberty and, if so, whether or not this was in their best interests.

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Comments are closed.