Sara Ryan says the protective instinct in any mum of a disabled child is always on overdrive.

“You’re so aware that there’s different expectations attached to them and you’re forever fighting that,” she says.

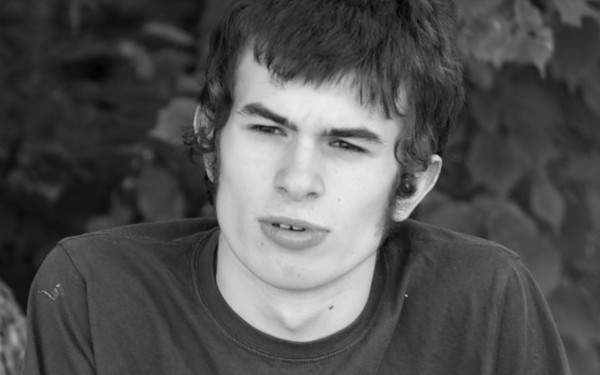

Sara’s fight for her son Connor Sparrowhawk started when he was as young as two-years-old, after a paediatrician wrote him off as a child she’d “probably need respite from in the future”. But it’s also one she has had to continue for more than four years since his untimely death at a specialist NHS learning disability unit.

On 4 July 2013, Connor was left unsupervised in the bath at the Slade House unit, run by Southern Health Trust. He suffered an epileptic fit and drowned. He was 18.

At the time the trust said Connor died of “natural causes”. But an independent investigation found his death was preventable, and an inquest ruled neglect had contributed to his death. It was only last year that the organisation accepted full responsibility, and last month it pleaded guilty to breaching health and safety laws.

Sara recently published a memoir, Justice for Laughing Boy, which documents the family’s fight for justice, but also “the cool kid” Connor was. A boy who loved his family and their dog Chunky Stan, London buses, heavy haulage trucks, human rights, sitting in the sunshine, and reading Horrible Histories.

“I wanted to write the book to present a picture of Connor as the boy he was, rather than the dead, disabled teenager he is flagged up as in local media,” Sara says.

“I also just wanted a record of what an enormous part of our family he was.”

‘It was always Mum’

Sara says in their family, Connor was everyone’s favourite, they all loved him and wanted to hang out with him, and he was an “absolute delight” to be the mother of.

“He was so cute as a baby,” she says. “He was one of those babies you could just eat, with the chubbiest little face and a laugh that was just hilarious.

“It was only when he got diagnosed [with autism] that the whole ‘system’ thing kicked in, the statementing, special schools, and endless appointments with people who don’t do anything. At home, he was just Connor.”

She recounts the times in those early years where Connor would be in pieces when she tried to reverse the car – “you don’t realise how much you reverse a car until you can’t” – or howling in the supermarket. But between the age of 11 and when he became unwell, Connor was just “so happy, content and lovely to be around”.

For Connor, “it was always Mum”. As he approached 15, Connor instigated ‘just you and me Mum’ birthday trips to London. When the vacancy for the chief of the metropolitan police came up, he told Sara: ‘Mum, you’ve got to apply for it’.

“Once he realised I was his Mum, which took him a while to work out, he looked to me for everything I think, which makes what happened really difficult,” Sara says.

“When he went downhill, he started to attack me and that was really shocking for all of us. I think that was when we realised he was seriously unwell.”

‘Chilled to the core’

Connor’s decline in health was unexpected and sudden, and he changed so much, Sara says. For three months, the family “limped on”. Sara and her partner Rich alternated working at home, while Connor spent most of his days lying on the floor of the downstairs toilet, with a wrench, fiddling around with the plumbing.

Sara recalls feeling “absolutely fearful” during this time. Fearful that Connor would hurt himself or someone else. Fearful that he would end up in the criminal justice system, where the percentage of learning disabled people is already “awful”.

“There should have been a well-trained team, used to dealing with this, who would come round and hang out with Connor, figure out what the problem was, make sure he wasn’t a danger to himself or anyone else, and work with him and us,” she says.

But there wasn’t. And when Sara’s friend told her about the unit, just down the road, with specialist staff and almost one-to-one care, she felt this was the only option.

“I remember being on the bus on the way home, I’d written the number down, and I was just absolutely chilled to the core that I was going to start this process. I didn’t stop shaking for ages… you’re about to admit your child into a unit. I had no idea at that point what was going to kick in, I just knew it was such an awful thing to do.”

‘Tumbling tears’

Sara didn’t know at this point that the unit wouldn’t be anything like it had been described. She remembers it now as a place where she had to ask permission to visit her son, how it always took a long time for the door to be opened, with no reason why, and where sometimes you would be greeted with silence, not a hello.

“Yes, [I felt shut out]. They said that because Connor was 18 it was his choice what he did, and they made out like I was ‘just interfering’ basically.

“I was absolutely petrified by that. I was really worried that I was going to ring up to visit him one day, and they’d say oh he’s decided to go and live in a shared flat in Didcot…when actually he was a schoolboy who was part of a family.”

She says it was heartbreaking to see Connor drugged in his early days in the unit, and turning up to find him asleep, with a plate of cold food on his bedside. He chose not to eat in there, and they let him, she says. His BMI dropped to 15.

“I was saying to them, you can’t just let someone not eat. This whole choice agenda and the way it is manipulated by health and social care, I find that really alarming.”

When Sara visited Connor in the unit, they did what they always did. They used to chat about all the things she knew he liked, like cows, and trucks, and make lists for his haulage company, how many tyres he’d need, and that he’d need a yard.

“He didn’t say this to me ever, but when we got the notes it was documented in loads of places that he was saying ‘My mum is going to come and take me home’.

“When I got those notes back two or three weeks after he died, god it was almost like the tears were just…I wasn’t even crying down. It was terrible, so distressing.”

‘Mother-blame’

In the weeks, months and years that have followed Connor’s death, Sara hasn’t had what she refers to as a “peaceful grief”. She remembers thinking at first that at least it was an NHS service, so everything would be properly dealt with.

Sara was quickly warned by a human rights barrister, who had been a reader of her blog ‘mydaftlife’, that Connor’s death may not be investigated properly. Then a solicitor was saying, “get the records, check the postmortem”.

“Everything they said might happen, happened. I was absolutely reeling. So reeling from his death, but I just couldn’t believe these things wouldn’t be done properly.”

The battle for justice that followed is something that Sara describes as a “terrible unpacking” of the events that led to Connor’s death, where the family have found out “more and more the level of how bad things were.” To make matters worse, Sara has also found herself being blamed by health and social care services.

She writes in the book that pinning the blame on ‘Mum’, rather than openly trying to establish what went wrong, is something that has “consistently floored” her over the past few years. The book includes examples of the ‘mother-blame’ concept from briefings, staff witness statements, and the records disclosed to the family after Connor’s death.

“For all the blame chucked my way, I’ve got a whole storage cupboard of guilt about what’s happened, obviously he died, I shouldn’t have taken him there, and all the rest of it.

“He shouldn’t have been admitted…I was like a block of ice, I don’t think I stopped shaking for about eight days after admitting him. That’s why this mother-blame thing is really painful as well…it’s not like we took him there on a whim.”

‘He got that from me’

Today, Sara feels that with the support of so many different people, her family has “achieved the unachievable” in the fight for justice for Connor. She says an awful lot of people have got in touch to say they are now fighting for inquests, and that she keeps hearing that within health and social care, his death has had an impact.

She adds that it’s really ironic that everything that’s happened since Connor died, is all the stuff he absolutely loved. He loved human rights and the law, he dreamt of owning buses and now there are three that have his name on them, as well as a truck.

“When I was writing the bits in the book about Connor’s strong sense of justice, I was thinking ‘he got that from me, he got that from me’…I was just thinking God, if you were here Connor, you would just bloody love this…

“That really does give me some comfort. He was always so special to us, he was always such an incredible young person, and I feel that’s become known in a way that I never dreamt it would do. We’ve done him proud.”

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

A very sad case Connor Sparrowhawk, but the love of his mother Sara and the determination to fight for her son as she knew him is a tribute to her and her family,and not to have his death forgotten.

“I was saying to them, you can’t just let someone not eat. This whole choice agenda and the way it is manipulated by health and social care, I find that really alarming.”

You’re far from being the only one Sara. RIP Connor.

”This whole choice agenda and the way it is manipulated by health and social care, I find that really alarming.”

We were made to feel we were trampling all over our son’s rights by trying to get ( largely non-existent) help for him. I’m not sure when professionals do it they really understand how many contexts, other professionals also take the same line -GP, school, social care – the lot. Then when things go very seriously wrong you are told ”You did the wrong things and caused harm”. There is massive resentment because you keep pushing and yet all these people go home to their child that society values, unlike yours.

The world could see the love and devotion Sara had for her wonderful son LB – she fought a long hard battle against a corrupt system who were more interested in safeguarding themselves than telling the truth.

As always Solidarity from Liverpool.

I am full of admiration for Sara and everything that she has achieved for her son with such dignity. I am finding it difficult to to be dignified in my fight with the local authority to ensure my daughter receives the care and quality of life she deserves . She is 10 severely autistic, severely learning disabledand non verbal she has been in an assessment unit for 11 months when her restlessness and aggression became too much for me to manage. In that time her self harming has increased alarmingly, she has been attacked numerous times by another resident child and has sustained injuries that do not match the accounts given.

I withdrew her early last month as I was so worried by her deteriorating behaviour and the lack of strategies in place to help her, activities outside of school were virtually nonexistent adding to her distress. The council refused to reinstate her former support package and stated I would have to go through a full assessment and refused to give any time scale for this to be completed. Within three weeks after coping alone as her sole carer I felt unable to go on. I had no choice but to return to the assessment unit (which had kept the bed open as they knew her to be high needs and high risk – yet failed to help me in any way ) The useless social worker failed to respond to the many emails sent pleading for help, phonecalls went unanswered and were not returned. CAMHS were equally useless. I look to the future and feel nothing but fear and despair.

Professionals appear to have empathy fatigue – if they ever had any empathy at all, the description of meetings with individuals who do nothing rings very true with me. Learning Disabled children and adults within the system are not treated as fully human, they are “other” and seemingly not entitled to the same level of care and respect as the rest of us. The system’s first priority is to protect itself, parents that speak up about poor practice and neglect are branded trouble makers and smeared at every opportunity.

Brave mother

Sara’s endurance as a grieving parent in the face of effective demonisation as a mother is extraordinary. There is so much that needs to change in our culture before we can begin to consider ourselves civilised. Those of us who are mothers, and parents, of autistic adult children stand with you Sara – we hope we never experience a loss like yours but over the years we have had to endure being sidelined, ignored and considered as trouble while our sons and daughters live less than fulfilled lives, sometimes far worse.

There are no words that can give comfort for such a senseless loss of their child.

And I have to ask of all professionals do you really understand the lives of the people you are providing services for and how your actions can impact them for better or worse?

Take this one small example

We had been told we would be able to participate in a meeting with professionals when our autistic son turned 18, prepared questions to elicit views from all the professionals present, arrived early and were asked to wait in another room while professionals had the meeting. When we were eventually invited in, a number of people (who did’ent know us or our son) had already left. This is what ‘excluded’ feels like and it is 100% normal practice. I’d go so far as to say it is the law..

Sara I am so sorry for the way your son was neglected, the dreadful way the health system treated you and the loss of your son. You are an admirable and dignified person with a lot of fight and determination! I can’t believe the appalling way Southern Health covered up the cause of Connor’s death and wouldn’t initially accept responsibility. Something clearly has to change for the better in the mental health system.

Connor truly was a remarkable young man but behind him was a wonderful, caring family. Well done for taking on the institution which is our justice system and winning. The sad thing about all of this is that we are led to believe that things will be done correctly in England and justice will prevail but really it is all bent and twisted and things covered up as it is all over the world. Nothing we believe is true and Sara should be praised in fighting for the truth and eventually finding it out! She should never of had to have done that!

As a parent of young people with autism I dread reading Sara’s book, as a person who comes in contact with people of all ages living with autism and experiencing such bad outcomes within the criminal justice system and health and social care I know I must but I know it won’t be easy reading. Why can’t we create safe services for families experiencing autism free from the parent blaming and shaming excuses that are always handed out in response to bad practice?