By David Jones

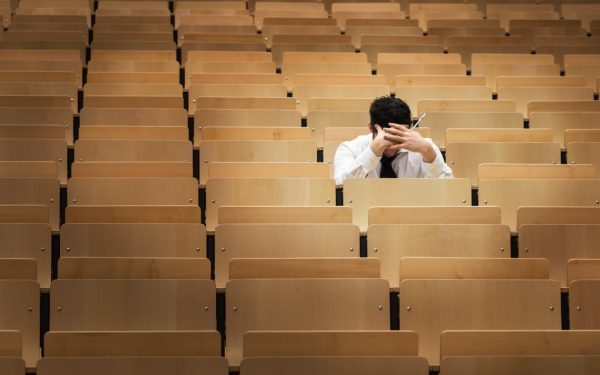

“I felt totally alone again” explained Joe, a care leaver who’d hoped university would be a transformative experience for him. Shortly after leaving for university however, Joe’s foster parents, with whom he’d been settled and supported since he was 15, separated. This devastated him and increased the sense of alienation he first felt as a child when he was taken into care aged nine.

In a new and unfamiliar setting, and struggling to maintain his studies, Joe discussed his anxieties with his personal tutor but says this provided no relief. “He was nice enough but couldn’t relate to my experience. In fact, he told me that he’d never met a student with my background.”

He was advised to contact the university’s counselling service, and admits he lost heart. “I had to go on a waiting list and you were offered five or six appointments with a counsellor. After two of these I realised I still felt low and it affected my studies. I would lie in bed and miss lectures and not care. I failed my first set of exams and then I left.”

Half of care leavers consider quitting university

Joe’s experience is not unique. Recent research highlights the need for enhanced support for students like Joe, who have been in care. It found that 51% had seriously considered dropping out, with the most common difficulties arising from a mix of health problems, money worries, high workloads and personal and family issues.

Care leavers face many challenges as they go into adult life and attending university can bring its own set of issues. In 2018-2019, only 6% of care leavers were known to be in higher education, and with half of these considering dropping out, what can universities do to help support, encourage, and improve outcomes for care experienced students?

More articles on care leavers

The research, ‘Battling the Odds: Pathways to University from Care’, was funded by The Leverhulme Trust and the ESRC Impact Acceleration Account at the University of Sheffield. It recommends that universities provide a dedicated care leaver champion – who must have specific knowledge of the needs of care experienced students – to help care experienced students navigate the unfamiliarity of university life.

Having researched the experiences of 234 care leavers at 29 universities in England and Wales – 80% of whom had been in foster care – research lead Dr Katie Ellis, lecturer in child and family wellbeing at the University of Sheffield, says that while many universities have a care leaver contact students can talk to, this service can be sporadic.

“During our research, we rang universities using the contact number they advertised for care leavers and were sometimes directed simply to the university switchboard. We then had to explain to the person on the other end of the line what a ‘care leaver’ was. Imagine doing that as a new student.”

“That just isn’t good enough. Universities should provide care leaver champions, who are familiar with these students’ issues and can advocate for them. And while generic counselling services are available at most universities, they generally offer only short term support.”

Mental health and university life

Of course any student, irrespective of their background, can suffer with their mental health or find university life demanding and difficult, but these issues can prove more acute for care leavers, maintains Ellis.

The research found that 68% of these students had experienced mental health problems while studying, but just 44% had received counselling. It also showed that while some students were aware of the availability of counselling, others were worried they’d be stigmatised for seeking support.

And although 71% received details of a care leaver contact, for those who hadn’t, university felt large and faceless. Add to this the 28% who arrived on campus bringing only what they could carry on public transport and the 41% no longer in touch with their carers, and it can make for a less than ideal start to university life.

“[Care leavers not being in touch with their carers] is often driven by the young person who sees university as a new chapter and a chance to start again. Many had experienced care which was less than ideal, and in those cases, students were keen to close the door and leave their care experience behind them,” adds Ellis.

An emotional burden

Having been in care remains an emotional burden for many of these students in other ways too. While 70% reported that they found it easy making friends, they were still aware of being different from their peers and reluctant to discuss their care background with them.

“In fact, over 50% found it difficult to share their past with fellow students, while 20% wouldn’t even confide in close friends they’d made at university,” says Ellis. “And this shows again why it is important for universities to offer a specialised care leaver contact.”

There need to be better lines of communication between local authorities and universities, she insists. “Both need to be much clearer when advising young people about what support is and isn’t available”.

Can care leavers expect their local authority to pay their fees?

The short answer is no. Ellis explains that students reported receiving very different levels of funding. “While one student had all of her expenses paid, including accommodation and fees, others received next to nothing.”

“Council support can be inconsistent and, accordingly, young people don’t know what they are entitled to. While some care leavers have their financial needs met – others don’t.”

Indeed, more than 25% of respondents reported that their local authority gave them inconsistent information regarding the financial support available, with some even saying they were denied assistance after initially being promised it.

“In one case the social worker told a student that should they achieve the required grades, all the financial support would be put in place,” explains Ellis. “When the student got the grades, the social worker backtracked on what he’d promised. Luckily the foster carer had kept their own copies of all the monthly meetings they had with social workers over the years. They were able to provide a signed copy of meeting notes that confirmed their claim and so the student received financial support.”

University culture

The study also calls for the option of alcohol-free accommodation, reflecting the recent decline in youth drinking, to make the transition to higher education easier for students who would prefer to live with other non-drinkers. This of course recognises that a drink culture still exists in universities.

“This would mean that like-minded students were able to live together without having to deal with behaviour that they find unacceptable,” Ellis says. “One girl explained that on returning to her room, there were piles of rubbish everywhere and sick in the kitchen sink. She had experienced the effects of alcohol abuse before going into care and didn’t feel able to manage living in that kind of environment. She needed a safer place and moved out to live with her boyfriend, which isolated her from the university experience. And this is an issue for 27% of these students.”

The study advises that universities register students with care experience early, so they are better placed to access the practical and emotional support they need.

“It can’t be right that someone struggles to afford Freshers’ week activities, which are an important introduction to the university environment,” Ellis explains. “These students have overcome significant barriers to fulfil their dreams of pursuing further education, and it’s vital that universities do all they can to make them feel welcomed and supported.”

Encouragingly, Joe is considering giving university another go.

“I got to thinking that I’d worked so hard to get there and I had no other options. There must be other students who have come from a care background who make a go of it. I’m still nervous at the prospect of returning but it feels like it’s now or never.”

David Jones is a pseudonym. He works in a residential children’s home.

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  ‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services

‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services  How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence

How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence  How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families

How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Comments are closed.