This article comprises of excerpts from Community Care Inform’s guide to Initial meetings with young people: an intersectional and systemic approach. The guide is by Nick Marsh and Jahnine Davis, PhD researchers exploring issues related to child protection and safeguarding. They are also joint directors of Listen Up Research, a community interest company, set up to elevate the voices and experiences of marginalised young people in practice.

The full guide explores how intersectionality and systemic approaches are useful lenses to use when working with young people, especially when considering initial interactions with services. It also works through an in-depth case study following a young person who appears not to want to engage with their social worker, and how the social worker approaches and manages an initial meeting.

Community Care Inform subscribers can read the full guide here.

First impressions

When we meet someone we’ve never met before, within a few moments both parties have made numerous judgments about the other – whether we like it or not, first impressions count. The same applies whenever we meet a young person for the first time. That initial meeting holds the potential to change the direction of that young person’s life – this includes what support they may be offered and which services they will be referred to. The outcome of this initial meeting will also be a deciding factor in whether a young person will meet with us again.

Intersectionality is a helpful lens in highlighting some considerations that can broaden a practitioner’s thinking when meeting a young person for the first time, support confidence and help you to use this important moment to establish a trusting relationship.

What is intersectionality?

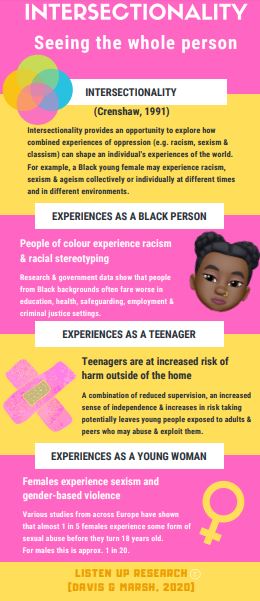

Intersectional thinking invites services and practitioners to explore how children and young people experience the world, how this impacts on the way they interact with others and the extent that they feel able to share their lived realities. These experiences are shaped and influenced by aspects of a young person’s identity, such as their ethnicity, age, gender, sexuality, class and abilities. Crenshaw (1991) noted that people’s interactions with the world are not solely based one aspect of their identity but instead are layered and multifaceted. Because the components of a person’s identity interrelate, they are experienced simultaneously.

For example, someone may experience racism, sexism and ageism collectively or individually at different times and in different environments.

Consider Jamel. He is 15 years old, black British and of Caribbean heritage. He is a victim of peer-on-peer sexual abuse. He is 6 foot tall, is often described as aggressive and has low attendance at school. It is likely that Jamel has experienced racism and biased behaviours not just based on his race and ethnicity but also because of how this intersects with his gender: he is a black male.

Jamel is therefore nine times more likely to be wrongly identified for being in a gang, more likely to experience stop and search (Lammy, 2017). In terms of how these characteristics intersect with age, likely to be perceived as being more adult-like and in less need of support compared to other children his age (Goff, 2014). Such experiences may influence Jamel’s sense of safety to feel comfortable about receiving and accessing support from professionals as a victim of sexual abuse.

‘Seeing the whole person’

Listen Up Research have produced an infographic to consider an example of intersectionality in more detail. Click the graphic for an expanded view.

Reflection points to develop your practice

- How might a young person’s identity (their ethnicity, gender, social class, sexuality, whether they have a disability) and their lived experience of different forms of oppression as well as the specific risks and harms you know about affect how they interact with professionals and services?

You might want to consider a young person you have worked with, or take the example of Keira who is considered in-depth in the full Community Care Inform guide.

Keira is 16 years old, black British and of Caribbean heritage. Keira is being sexually exploited. Keira has had social workers in her life, off and on, for the past three years. Keira doesn’t like social workers (or professionals more generally); she feels they have ruined her family’s life. She had spoken about the abuse to one of her previous social workers. This information was shared with her mother without Keira’s consent. - One option Keira’s white male social worker considers is that she may want a black worker to support her instead. Why might assuming this be problematic?

- Frequently services and practitioners do not reflect the diverse communities, children and families they serve. In such circumstances, how can individuals, teams or organisations better equip themselves to meet the needs of the communities they serve?

- To help him set up a meeting with Keira and reflect on how to establish a relationship with her, the social worker contacts one professional she is known to trust, her school counsellor. With Keira’s agreement and input on where they should meet, she and the consellor meet the social worker for him to hear from them about what has worked in building their relationship and how he can support her. By meeting Keira on her terms and with an advocate, the social worker has gone some way to redressing the power imbalance and adopt a children’s rights approach. How else might you do this with young people you work with? Are there other ways you can work with different professionals to improve interactions with young people?

Intersectionality and systemic thinking (which is discussed in the full guide) challenge individuals and services to reflect and review how their own positions and perceptions of the world influence everyday lived experiences in both personal and professional arenas. These approaches allow practitioners to think critically, widen their lens and see the world through the eyes of the young people they support. They provide different options to how we approach initial meetings and overall practice.

Meeting young people where they are in their lives requires attention and sense checking to ensure our own beliefs and experiences don’t overshadow the opportunity to get to know the young person sitting in front of us.

First impressions count. Time, consideration and a willingness to understand the lived realities young people experience is central to shaping that first interaction.

Find the full guide here on Community Care Inform Children. Not sure if you have access to Community Care Inform through your local authority of organisation or have other questions? Find help here.

Further resources for Community Care Inform subscribers

- Safeguarding black girls from child sexual abuse: messages from research

- Cultural competence: lessons from research

- Anti-discriminatory and anti-oppressive practice education

Further reading on Community Care

References

Crenshaw K (1991)

‘Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color’

Stanford Law Review, 43(6) pp.1241-1299

Goff P, Jackson M, Di Leone B, Culotta C and DiTomasso, N (2014)

‘The essence of innocence: Consequences of dehumanizing Black children’

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(4), pp.526-545

Lammy D (2017)

The Lammy Review: An independent review into the treatment of, and outcomes for, Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic individuals in the Criminal Justice System

London: Lammy Review, Ministry of Justice

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Comments are closed.