The duration of care proceedings reached 10 weeks over the 26-week target following the coronavirus lockdown, despite the number of cases starting being 4% less than during the same period in 2019.

Ministry of Justice (MoJ) figures showed that, from April to June 2020, the average length of proceedings was 36 weeks and the proportion completed within the 26-week target was only 34%, down from 41% in the same quarter in 2019.

The rise in the duration of proceedings at a time when cases fell reflects the impact of the lockdown, during which face-to-face hearings were largely stopped.

Cases were held virtually, where possible, and continue to be so, but this is more difficult for complex cases and is often not possible at all. Overall, 30% fewer public law cases were dealt with by the courts as a result, a trend reflected more strongly in adoption cases, for which there was a 24% drop in cases and a 52% decrease in cases dealt with.

Upward trend

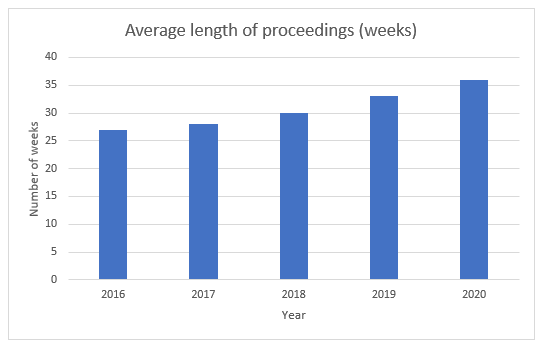

The rise in the length of care proceedings since 2016 (source: Ministry of Justice)

The duration of care proceedings has been rising consistently since 2016 when it stood at 27 weeks, two years after the 26-week target was set in law by the Children and Families Act 2014.

Commenting on the figures, Sara Tough, chair of the Association of Directors of Children’s Services families, communities and young people policy committee, said: “The Public Law Outline has benefitted children and families in terms of reducing unnecessary drift and delay in the system, but our main aim should always be meeting the individual needs of a child or young person, even if this falls outside of the 26 week limit.”

Court capacity

Tough added that “in person hearings were largely unavailable for the period covered [April-June] and remote hearings often take longer and are not well suited to complex, contested hearings”.

In its response to the figures, Cafcass said that “most hearings involving significant decisions relating to children are required to take place in-person”.

A spokesperson added: “Due to a range of factors across the family justice system relating to the pandemic, including the limited capacity in courts and the need for crucial decisions regarding the futures of vulnerable children to be properly considered, this has meant that the average duration of cases is longer.”

Nagalro, which represents family court advisers, said its members struggled to complete some assessments altogether because of the need for face-to-face contact with children and families, and remote working proved far slower.

A spokesperson for the organisation said: “The adjournment of court hearings and remote interview assessments seem to have resulted in the current proceedings being extended due to the lack of timely evidence available to the court and a fall in the application for placement orders.”

The Ministry of Justice said that to tackle the impact of Covid-19 it had increased the number of remote hearings and was making sure the most urgent cases are prioritised.

“Despite the challenges presented by the pandemic our focus remains on concluding care proceedings as quickly as possible, and we continue to work across the family justice system to improve the process and reduce the stress on children,” a spokesperson said.

Virtual hearings research

Research into the impact of virtual hearings, published by the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory (NFJO) in April showed that virtual hearings could work efficiently but there could also be “significant challenges” relating to some contested care cases and cases involving groups with certain vulnerabilities.

Commenting on the MoJ statistics, NFJO director Lisa Harker said that virtual hearings were heavily reliant on everyone involved having access to adequate technology. She added: “Virtual hearings will never be able to replace face to face in all cases.”

Harker continued: “The picture has clearly moved on since April, for example many courts have rolled out new video conferencing systems since then and hybrid hearings have started operating in some places.

“It is clear that it is increasingly difficult in the current circumstances to meet the 26-week target. Delays in decision making are bad for children and we should not lose sight of this – but hearings have to be fair and just to those same children proceed.”

Is a 26-week target achievable?

Nagalro said it believed the 26-week target was still meaningful and said that there was provision in the legislation allowing extensions of a case by up to a further eight weeks at a time “if the court considers that the extension is necessary to enable the court to resolve the proceedings justly’”. More than one extension period is permitted.” Nagalro believed that these extension applications should be used more frequently.

The MoJ spokesperson added: “As society and the economy begins to recover from the impact of Covid-19, it is expected that case volumes will return to historic trend levels and may even temporarily exceed the pre-covid-19 volumes as the backlog of cases is processed. We are working with representative bodies to understand the expected demand and will continue to monitor future trends in both volumes and timeliness.”

Domestic abuse orders on the rise

Reflecting the impact of the lockdown on domestic abuse, applications for relevant ordersincreased by 24%, compared to the same quarter in 2019. Tough said that the sharp increase of domestic abuse applications was “concerning” but added ADCS were reassured to see the number of orders granted to protect victims had also increased, by 17% Most of those granted were non-molestation orders, which injuncts perpetrators not to do certain actions.

Tough continued: “Domestic abuse is the most common reason children and families come to the attention of children’s social care, the Domestic Abuse Bill must go further to prevent it from occurring in the first place.”

The bill, currently going through Parliament, places a duty on local authorities to provide support to victims and their children in refuges and other safe accommodation, and strengthens domestic violence protection orders and notices, which are designed to provide immediate protection for victims, and puts the guidance regarding the domestic violence disclosure scheme, among other measures.

In June, in evidence to the committee of MPs scrutinising the bill, the ADCS said that “many of the proposed reforms are reactive rather than preventative and the drivers of abuse are overlooked”, whilst also criticising the lack of a “funding package that fully reflects the scale, reach and severity of this pervasive issue”.

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Comments are closed.