A second council has stopped taking in unaccompanied asylum-seeking children after a rise in arrivals saw independent reviewing officers’ (IROs) caseloads top 70.

Portsmouth council has joined Kent in saying that it is at capacity, meaning children arriving at its port are having to be moved to other local authorities under the national transfer scheme for unaccompanied children.

The news comes with a third authority, Croydon council, home to the national asylum intake centre, considering its capacity to take on more unaccompanied children as it battles severe financial problems.

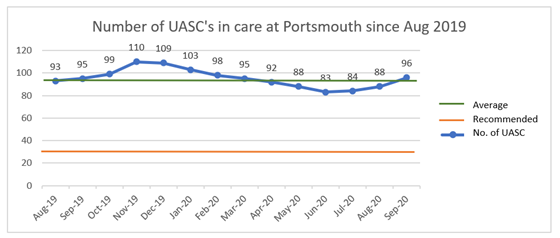

Portsmouth’s struggles are the result of caring for an average of 90 unaccompanied children over the past two years, above the quota of 31 allocated to it under the voluntary transfer scheme, which is designed to share responsibility between councils equitably but has not done so.

While numbers dropped in the spring as a result of Covid, they have picked up since the summer, with 22 unaccompanied children arriving in Portsmouth between August 18 and September 22 and a further 15 arrived from then until 16 November.

IRO caseloads affecting ability to meet statutory requirements

Alison Jeffery, the council’s director of children, families and education, said: “All looked-after children require allocation to an independent reviewing officer (IRO). Caseloads for each IRO should sit between 50 and 70, with our IROs now holding caseloads of 70+. This impacts on the ability and statutory requirement to meet the needs of all of our looked-after children and care leavers.”

Jeffery also pointed to the fact that the high numbers of arrivals over the past two years meant that the council was now supporting significant numbers of unaccompanied care leavers.

She added: “Despite having strong in-house fostering and supporting housing services in Portsmouth, there are limited placements available and the services are being stretched. As a result, we have had to make extensive use of placements outside of the city, often in London.

“These young people are inherently vulnerable to being trafficked and exploited, and providing safe care requires close working with education, health and the police. This is difficult to achieve from a distance without the partnership links we have in the city.”

Now, when new asylum-seeking children arrive into Portsmouth – as they continue to do so – the UK Border Agency makes contact with the Home Office, who transfer the children to other authorities through the national transfer scheme.

Jeffery said that a number of neighbouring authorities had capacity to accept arrivals:

“Portsmouth is not far from a number of authorities in the region which are well below their national transfer scheme capacity at the moment, therefore there should be no barrier to support being provided quickly.”

Related articles

Following Kent’s decision in August to stop taking new arrivals, the Home Office launched a consultation on reforming the transfer scheme, including through potentially making it mandatory, to share responsibility for unaccompanied children more equitably.

Transfer scheme ‘must be mandatory’

Jeffery said she backed mandating the scheme, a position also taken by Kent.

“The need for a mandatory national transfer scheme is pressing and is the obvious solution to the problems we and Kent have experienced,” she added

The Association of Directors for Children’s Services (ADCS) and the Local Government Association have both backed an alternative proposal for a voluntary rota system sharing responsibility between regions for arrivals.

Jenny Coles, president of ADCS, said in a statement in response to the Home Office consultation: “It is right that Kent and other gateway authorities should not bear the brunt of supporting the rising number of asylum seeking children arriving alone on UK shores.

“Any new arrangements need to be sustainable and have children and young people’s best interests at heart; we believe that the proposal in the consultation for a regional rota system has a better chance of achieving a long term equitable solution.

“However, a regional rota system is not a long term solution to the long standing issues that government must address, including placement sufficiency, funding levels including funding for care leavers, age assessment, and more timely immigration decision-making for children.”

‘Responsibility must be shared’

Judith Dennis, policy manager at the Refugee Council, said that unaccompanied children arriving in the UK should be taken into local authority care “immediately” and that there cannot just be two or three councils doing all the work “while the others just look the other way”.

Dennis said responsibility needs to be shared equally and that the Home Office and ADCS must act now.

“This is what the national transfer scheme is designed to do, but it requires local authorities to be proactive and offer to help. This isn’t happening as much as it needs to, which means some children are missing out on good quality care. The Home Office and the Association of Directors of Children’s Services cannot keep putting this off, they must complete the review and implement changes now.”

A Home Office spokesperson said: “Our efforts remain focused on ensuring every single unaccompanied child receives appropriate support. We have been working incredibly closely with Portsmouth City Council to move children into new local authority placements, where it is in their best interests to do so.

“We are currently considering the responses to the consultation to improve the national transfer scheme, which transfers unaccompanied asylum seeking children to different local authorities, to make sure the responsibility for these children is spread evenly and fairly.”

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

There’s an absolute scandal of the local authorities which let children & their colleagues down.

In the whole of the County of Northumberland there is one unaccompanied asylum seeking child currently being looked after

Confused!

The Children Act 1989 is clear about Local Authority responsibilities to section 17 children in need in their area. AND: a child in need to whom a local authority owe a DUTY to provide accommodation under section 20 of the Children Act 1989*.

How are Kent and Portsmouth not acting illegally? It is a DUTY! Not a optional extra?

Reference.

https://england.shelter.org.uk/legal/housing_options/young_people_and_care_leavers/Homeless_16-_and_17-year-olds

clearly there are challenges and placement sufficient central gov funding relevant. However, mandating a rota is not necessarily equitable. Many LA’s still have a far higher proportion of cic per 10 than kent, Portsmouth so any mandatory scheme which places additional young people on to such authorities is even more disproportionate

The way in which asylum seeker children are being managed in Britain is quite similar to the way the wole asylum issue is being managed by the EU i.e. the frontline European states and frontline British councils are being left to bear the brunt of the work.

Lol….IRO Caseload of 70? Surely I have read that wrong… try 130..

Sounds to me like you have it easy.

the choice of picture on this article is interesting