Half of Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (Dols) cases are breaching legal timescales for completion after a landmark Supreme Court ruling in March triggered a nine-fold rise in monthly referrals to councils, a Community Care investigation has found.

Social workers welcomed the ruling’s extension of human rights protections but said resources are urgently needed to help frontline teams cope with the flood of cases coming in.

Under the Dols, local authorities must assess whether people who lack capacity to consent to their care arrangements are being deprived of their liberty in care homes or hospitals and, if so, whether this is in their best interests and necessary to protect them from harm. The Dols are designed to provide independent scrutiny, by social workers and health professionals, of these care arrangements.

The Supreme Court ruling

The Supreme Court judgement, in the cases of P v Cheshire West and Chester Council and P&Q v Surrey County Council, brought in a revised test that effectively lowered the threshold for deprivation of liberty in care.

It also rendered irrelevant factors that had been allowed for in the past, such as whether the person objected to their care arrangements.

The judgement was welcomed for extending key human rights safeguards to a broader group of vulnerable people. But it meant that, overnight, many people in care homes, hospitals and supported living arrangements suddenly met the threshold to have their care arrangements assessed or reassessed to see if they were deprived of their liberty and, if so, whether or not this was in their best interests.

Prior to the Supreme Court ruling (see box), and under previous case law, the safeguards were often not applied if the restrictions on a person’s liberty were viewed as normal for someone with that level of disability, or if the person or their family did not raise objections. But the ruling rendered these factors irrelevant, and effectively lowered the threshold for cases requiring assessment. In doing so, it extended important human rights protections to a broader group of vulnerable people and, as a result, triggered a surge in referrals for Dols assessments.

The impact of ‘Cheshire West’

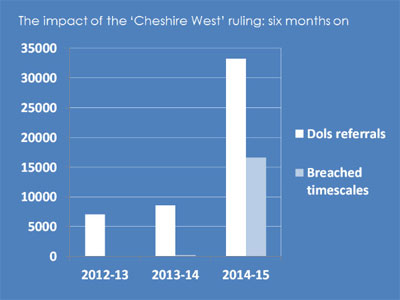

Six months on from the ‘Cheshire West’ judgement, our investigation, based on data obtained under the Freedom of Information Act from 103 local authorities in England and 19 councils and health boards in Wales, reveals the massive impact it has had on the adult social care system.

In 2013-14 councils received 8,455 requests for Dols assessments; since April this year they’ve already had 32,988 referrals. The figures mean average monthly referrals have risen from 713 in 2013-14 to 6,643 in 2014-15. The effect of the dramatic rise in cases is clear. Last year 2.2% of cases breached timescales; so far this year 50% of cases were not completed in time.

Councils have also seen more legal challenges to deprivations of liberty and one local authority has sent a ‘systemic abuse alert’ to an adult safeguarding board warning that it could not meet the ‘Supreme Court challenge’ due to a shortage of resources.

How councils are responding

Local authorities say they are tackling the ‘unprecedented’ demand by screening the paperwork of providers’ Dols applications to identify high priority cases and dealing with these first. Councils know that timescale breaches leave them vulnerable to legal challenges but are working on the understanding that, in the event of a legal challenge, the Court of Protection will be sympathetic to time limit breaches but critical of councils that cannot demonstrate they had clear processes in place to prioritise risky cases.

The court ruling has also intensified a shortage of best interests assessors (BIAs), whose role is to determine whether a person is, or will be, deprived of their liberty and, if so, and whether this is in the person’s best interests. Councils are scrambling to train up more social workers as BIAs in a bid to boost assessor numbers, but many training courses are oversubscribed and, even if a place is secured, training can take months.

We found that the shortage of trained staff in councils means local authorities have already spent £1.4m on independent BIAs in 2014-15. That’s almost three times the £550,000 spent across 12 months in 2013-14.

Frontline staff say the ‘Cheshire West’ judgement is a positive move that should better protect the human rights of vulnerable people. But they warn that a lack of resources to meet the sharp hike in cases is making it ‘impossible’ for Dols teams to meet timescales and practise lawfully. Triaging cases, social workers say, is the safest and most pragmatic approach but the scale of referrals flooding in risks complex cases slipping through the net.

Concerns have also been raised that moves to pull more BIA-trained social workers on to Dols work full-time to clear backlogs is depleting other teams with key duties, notably safeguarding services and approved mental health professional teams, of experienced staff.

Social care reaction

In response to our findings, social care leaders called on the government to work with councils to address ‘very urgent’ concerns over a shortage of resources to meet the post-Supreme Court ruling demand. The government said it was monitoring the impact of the judgement but said councils had already been given £35m to implement Mental Capacity Act work in 2014-15, including the Dols. Local authorities estimate the Supreme Court ruling’s impact will cost at least another £88m on top of this.

Daisy Bogg, a social worker and BIA trainer, said the resourcing issues needed to be addressed urgently to help frontline staff who are struggling to keep up with referrals.

“We’re six months on from the judgement and it feels like all we’ve heard is the that talks are going on between government and [adult social services] directors and there’s no sign of a clear position from government. That isn’t helping the guys on the ground. The political stuff keeps going on, meanwhile teams are trying really hard to implement the safeguards properly. But the system is in meltdown in some areas,” she said.

Robert Nisbet, a social worker and independent trainer, said that triaging cases was the only way staff could practically manage the surge in demand. But he warned that the process had risks.

“Screening on paperwork very much depends on the quality of information and the accuracy of the information you are getting. It used to be that you’d be able to take down the basic information as a BIA and then just get out there and assess. That was the gold standard of practice but pragmatically, given the numbers of cases coming in, that’s now been thrown up in the air,” he said.

How deprivations of liberty are authorised

Deprivations of liberty in care homes and hospitals must be authorised under the Dols scheme. Each Dols cases involves six assessments, the most significant of which is the best interests assessment, carried out by the BIA. The BIA – a specially trained professional, usually a social worker – also coordinates the process, which is estimated to take between seven and 15 hours per case depending on complexity.

Where a person is already receiving care that may constitute a deprivation of liberty in a care home or hospital, the provider has to request an ‘urgent’ Dols authorisation from the local authority. These cases have to legally be assessed within seven days, although councils can grant a further seven day extension in exceptional cases. Standard authorisations, used to authorise a deprivation of liberty in care arrangements that have yet to start, must be completed within 21 days. Authorisations can be granted for a maximum period of 12 months before requiring review, so the increase in demand faced by local authorities is not simply a short-term spike.

Deprivations of liberty in care settings not covered by the Dols, such as supported living or home care arrangements, must be authorised by the Court of Protection. These applications are prepared by local authority legal teams, who are also under extra strain in the wake of the Supreme Court ruling.

More findings

Six months on from the ‘Cheshire West’ judgement, other findings from our investigation found that:

- The impact has varied locally: There was significant local variation in breach rates. The average breach rate per council in 2014-15 was 37% in England and 47% in Wales. The highest breach rate was in Medway, where 229 of 231 referrals (99%) breached timescales. However, 23 local authorities said they had met all timescales in 2014-15 despite the extra pressures.

- Legal challenges are rising: In the first five months of 2014-15 local authorities had 61 legal challenges brought over deprivation of liberty cases. In the 12 months of 2013-14 the councils had received a total of 49 legal challenges.

- Safeguarding concerns have been raised: Cornwall council raised a ‘systemic abuse’ alert with the local safeguarding adults board over the council’s inability to safeguard people under Dols, due to a lack of resources to meet the post ‘Supreme Court challenge’. The council said it wanted to ensure there was independent scrutiny of its response to the judgement. The councils said its “principal difficulty is one of resources and the availability of suitably trained staff to implement the DoLS for the greatly increased numbers. The council referred its concerns into the adult safeguarding process while it took urgent steps to address problem.”

- Stacks of referrals have been held back: Evidence from council reports shows that the referrals received so far are only likely to be a fraction of those that could meet the Supreme Court test as care homes and hospitals are delaying applications. In some cases, council reports say this is due to them ‘ignoring’ or not understanding the implication of the Supreme Court judgement. In other cases it is deliberate:

- We found one example of a council agreeing with a care provider to delay sending in 30 referrals to help with ‘backlog avoidance’.

- In a second case, a council report showed that some homes had delayed in sending in referrals as they were ‘sympathetic’ to the pressures on the local authority. In the report, the council’s Dols lead said that this was often happening ‘to the detriment’ of the person. The report shows that the Dols lead contacted the homes and told them to make the applications.

- A third council report we obtained showed that a local acute hospital had still to send in applications. The hospital had conducted an initial scoping exercise and identified a potential 35,000 referrals. This alone would lead to the Dols team facing a 350-fold increase in cases, the report showed.

‘Urgent action needed’

Responding to our findings, David Pearson, the president of the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (Adass), said directors supported the intentions behind the Mental Capacity Act and Dols but had alerted the government to the impact that the Supreme Court judgement would have on services, at a time when social care has had to make 26% savings over the past four years. Adass has called on the government to bring supported living arrangements within the Dols scheme and to provide more funding more services.

“The government has so far not agreed to our proposals for action on the change of the law but have referred this to the Law Commission for what is likely to be a lengthy review. They have not agreed to the request to fund the increased activity and have stated they want to see how this progresses and receive further evidence of the increase in people who need this support,” said Pearson.

“This matter is very urgent and the government needs to share responsibility with us for urgently responding to the challenge of getting this right for people who lack capacity.”

Izzi Seccombe, chair of the Local Government Association’s community wellbeing board, said: “These alarming figures back up our previous warnings that councils would buckle under the financial pressure of a rise in assessments. We completely agree with the principle of having broader, more robust checks for people needing care, but the government needs to provide adequate funding so that councils have the time and money to do this properly.

“Failure to do this will have a hugely damaging impact on crucial social care services on which people rely and will lead to more vulnerable people left facing long waiting times for assessments.”

Mathieu Culverhouse, an associate solicitor at Irwin Mitchell, who was involved in the Supreme Court judgement, said “It was anticipated that the Supreme Court’s judgment would lead to a significant increase in applications for Dols assessments and this is now reflected in these latest figures. This increase is to be welcomed, as it means that large numbers of vulnerable adults who were not previously considered to need Dols authorisations will now have the benefit of regular reviews of their protective care regimes.

“It is concerning that in many cases the assessment process is not taking place within the required time limits and it is to be hoped that the government will take note and provide the necessary resources to ensure that Dols assessments can be carried out promptly in all cases.”

A government spokesperson said: “We want to make sure that the Mental Capacity Act is used to protect and empower people receiving care and support.

“We have given local authorities £35 million to do this but we know the Supreme Court ruling has had an impact on workloads. The Health and Social Care Information Centre is collecting data on this impact and we will carefully consider the results when they are published shortly. We’re also streamlining the process for applications whilst still protecting people’s rights.”

Update to article: 10.45am, 2 October

The day after Community Care’s findings were released, our conclusions were underlined by official figures showing the hike in Dols cases in England in 2013-14. The figures from 130 of England’s 152 councils, collected by the Health and Social Care Information Centre, showed:

- the councils received 21,600 Dols applications from April to June 2014, compared with 12,400 in the whole of 2013-14, a 597% increase in monthly referrals;

- of these, 51% were authorised, 12% were not authorised, and 36% had not been withdrawn or not signed off by the council as of September 2014.

The HSCIC figures do not distinguish between applications that were withdrawn and those that had not been signed off by the council as of September 2014, but suggest timescales were being significantly breached in many cases.

The HSCIC report was the first in a series of quarterly collections, commissioned by the Department of Health to identify the impact of the Cheshire West case.

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

I find it interesting and not a little worrying that the vast majority of the talk so far regarding deprivation of liberty post-Cheshire West has been about the increase for BIA authoristaions under DoLS. Let’s not forget that another major consequence of the judgement was that the concept of deprivation of liberty now (rightly) applies to individuals in other settings such as independent supported living, Shared Lives (adult ‘fostering’) and potentially other domestic settings and even day services. The Court of Protection are anticipating a significant increase in the number of application for authorisation in these cases also, yet it seems local authorities are doing little to address this.