By Amanda Boorman

There has been a case highlighted on social media this week about a woman who has fought tooth and nail to be a mother to her child. She first went to court in an attempt to avoid her daughter being adopted, and a second time to have meaningful contact with her once she had been adopted.

The judge stated she was no longer the child’s mother in any way post-adoption and had no remaining ties to the child. So that’s all alright then.

My adopted daughter came to me aged five. In my assessment as a ‘good enough’ parent, one of my key questions (in amongst the myriad asked of me and my family) was, had my daughter’s mum been supported enough?

Was I, a financially privileged person, going to be given the child of a woman who cared and loved but needed financial support and services in order to translate that into good enough parenting?

No family contact arrangement

I was assured by my child’s social worker that I was receiving her, via foster carers, from a cruel and abusive situation and the no family contact arrangement in place (including siblings) was valid and needed for safety and permanence. Advice was given to avoid certain areas where the ‘monster mum’ may be lurking, intent on snatching her child or smacking me one.

My adopted daughter told me in the very early days, within weeks of placement, that she intended on buying a motorbike and that I was to ride pillion to the pub where I would wait outside and she would go in and shoot her mum and dad. Then we would come home for tea. Evidence enough that we should just forget all about them?

Fugitives through adoption

Meanwhile, we spent much time and thought planning to avoid detection by them. No school photos, no Facebook photos, don’t drive to this place or attend that event. Fugitives through adoption.

Each case is different and I know the arguments about extreme complexity, confusion, security, re-traumatisation, and parents who are so dangerous and cruel that they give up the right to ongoing relationship with their children.

Whitewashing history

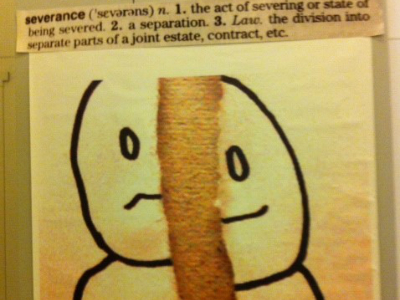

On the other hand there are many parents, particularly women, who are victims of society, sub-standard state care and who may have been victims of abusive men as both children and adults. This doesn’t mean you can put their needs before those of their children, but it doesn’t discount being humane towards them. I find it a ridiculous and quite inhumane notion to think that severance by law whitewashes emotions, identity and history.

I didn’t run with the drive-by shooting solution. Instead I went with open dialogue with my daughter from the very start: a non-ownership approach. Eventually this led to me contacting my adopted daughter’s family independently. After an initial meeting in a local authority office, I met them alone several times and ‘assessed’ them as I would anybody I met who might play a future part in my family life.

Long Lost Family

I found a mum whose life story you wouldn’t wish on an enemy and a gentle older dad who was proud, non-compliant and frustratingly helpless in the face of it all. I’m not sure what they made of me on first meeting, but if it was bad they hid it well with politeness and what seemed like genuine warmth of emotion.

Eventually there was a reunion far more visceral and messy than those you might see on Davina McCall’s Long Lost Family. In the following years, between the age of 8 and 18, our daughter was shared by two mums. She hated us and loved us both for different reasons. It wasn’t surrounded by rainbows and it was very hard work for us all practically, financially and emotionally. We didn’t ‘do contact’, we did human relationships.

Rights of adopted people

As founder of a charity which fights for the rights of adopted people, I know of those who want nothing to do with parents who harmed them greatly. The majority, however, have to start searching as teenagers or adults for the bits of missing information that rightly belong to them and for people they are linked to forever, come what may.

As an adult our daughter has all the information needed to conduct her independent relationship with her mum, and wider family, on her own terms and in a way that feels right and safe for her.

At this point there is, and will always be, sadness and anger at the need for such a drastic separation from them as a child, but also an understanding that it was necessary at the time. She also avoids having to enlist Davina McCall to find out who she is and where she came from.

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

This is a really profound point. We are adopting a little boy who has a Mother that life has been very cruel too in every single sense. We are not naive (well, we’ll see) but we have no intention of transforming the decision to protect her child into a quasi-judicial decision to punish his Mother for her situation and the impact it had on her. She has been punished enough. What that looks like over time we will see, but we are cannot be a ‘castle family’ – pulling up the drawbridge in the hope that somehow reality and truth can be avoided.

Excellent article, very moving.

The author’s point about the limits of the judge’s statement, that her child no longer had any legal ties with her birth mother, is very true. Legal ties or not, these are the parents who conceived and gave birth to her daughter, and she and her birth parents will always hold an important place in each other’s thoughts and feelings. A change of legal status cannot nullify that, and law should be framed to take account of it, instead of being framed in a way that encourages the ‘clean break’ that doesn’t actually happen in adoptees’ feelings.

Having an ongoing relationship with birth parents won’t work in every adoption, and needs to be managed carefully. However, I do think it needs to be considered far more often than is currently the case, and there should be a higher level of expectation of people considering adopting that they will be open to this. However, I expect that Martin Narey would take the view that this would scare away potential adopters, and hence it is unlikely to be adopted at the present moment.