It was spring 2015, recalls Trish Leivesley, now child criminal exploitation lead at North East Lincolnshire council, when something “really weird” came to her attention.

A 16-year-old, little known to youth justice services, was the victim of a serious stabbing. Instead of reporting it he returned home and initially tried to conceal his injury.

A week later, two more young people were stabbed, with all three incidents appearing to be linked to class A drug dealing. Over the next few days, a number of young people considered high-risk and vulnerable by youth offending services showed up with unusual injuries that did not correlate with their explanations of fighting or falling off motorbikes.

“[In Grimsby] it’s not unusual to see brawls or public order offences,” says Leivesley, adding that while the area, like many coastal towns, has high levels of deprivation and drug use it had little history of gang violence. “But over a one-month period we had three stabbings, incidents involving lacerations – and then reports of weapon-enabled offending and knife fights. I said to my manager – ‘I’m concerned we’re seeing a significant shift’.”

In the preceding months she had also noticed a number of boys being referred to North East Lincolnshire’s multi-agency sexual exploitation panel.

They exhibited troubling signs – frequently going missing, being found outside their local area, not abiding by curfews, and sometimes dressed in new items of clothing. One, who was in care, came home one day with blood in the back of his jogging bottoms, triggering fears he has been anally raped.

But no evidence could be found of sexual exploitation. “I was saying, ‘No, this is something different’,” says Leivesley.

By November 2015, following a peer review carried out by the Home Office, it was confirmed North East Lincolnshire had a serious problem with county lines drug dealing.

‘A perfect storm’

The term ‘county lines’, which references the phone lines used to sell drugs, has become commonplace in the news and usually implies young people – who call it ‘going country’, among other names – being trafficked far from urban areas to work in lucrative provincial markets. But comparable processes can see them being sent much shorter distances, for instance between neighbouring boroughs. Local young people may also be groomed by out-of-town networks.

Listen to our free podcast on criminal exploitation and county lines

In late 2016, a National Crime Agency report found 80% of police forces were reporting criminal exploitation of children, “typically to deliver drugs to customers, using a combination of intimidation, violence, debt bondage, and grooming to control them”. That figure has since risen.

Adults with mental health and substance misuse issues are also being exploited, with homes often ‘cuckooed’ or taken over by organised crime networks to provide venues from which to sell drugs. Statutory services, including children’s social care, have struggled to get to grips with the safeguarding challenge posed by child criminal exploitation (CCE), which sits within a wider context of rising knife crime. In London, Rhiannon Sawyer, the Children’s Society’s area manager for children and young people’s services, says she’s heard the situation likened to a “perfect storm”, exacerbated by austerity and, in particular, youth services cuts.

“Fast food restaurants and ice cream bars have become like new youth centres – but there’s no trusted adult or designated safeguarding lead in there [to spot] children being groomed,” she says. “Poverty is the biggest driver, but that doesn’t mean children from better off backgrounds can’t be affected – exploitation can affect any child in any community.”

Signs and barriers

A toolkit published in December 2017 by the Children’s Society set county lines in the context of the Modern Slavery Act 2015, as being likely to involve trafficking. It also listed indicators – ranging from missing episodes to ‘plugging’ drugs in their vagina or rectum, the likely cause of the boy’s injuries in Grimsby, Leivesley says –and vulnerabilities including school exclusions, neglect and exposure to certain locations.

But, points out Janet Webb, a principal lecturer in child health and welfare at the University of Greenwich, the fact that many risk factors may be nothing to do with home life can cause a blind spot for social workers.

“Their focus has been on signs and symptoms of abuse [within the family],” she says. “There’s a lack of awareness – and my own work suggests people are unable to recognise vulnerability [in a criminal exploitation context] – or recognise it and don’t know where to take it.”

Former dealers interviewed for a recent Community Care article mentioned how their lived environment of children’s homes and pupil referral units made them “easy prey” for gang members, and that even well-meaning social workers could be “out of their depth” in terms of trying to intervene.

Meanwhile a serious case review into the 2017 shooting in Newham of 14-year-old Corey Junior Davis, published this autumn, found professionals – including social workers – failed to identify him as a victim rather than a criminal.

Children’s services’ effectiveness, including around information sharing, was reduced by social worker turnover, the review found. But multi-agency systems in place at the time of Corey’s death “did not effectively respond to [him] as an at-risk child”, it said.

Multi-agency responses

In North East Lincolnshire, Leivesley acknowledges that things were “not set up to deal” with issues of CCE when they first emerged. In response, the council changed its multi-agency arrangements to look at all children missing, exploited or trafficked, in the round.

We stopped looking just from a CSE perspective, in order to understand that exploitation is exploitation

Every week, health professionals, youth offending services, the police and a specialist social worker from the council’s front door meet to discuss “anything exploitation-related” and where the best level of support sits for each child.

Other local authority areas we speak to report conducting similar integration processes as an essential part of their response to CCE and county lines activity. An Association of London Directors of Children’s Services report published in May noted many boroughs in the capital were now considering many forms of exploitation – which can interlock with one another – within multi-agency forums, both in terms of strategic and incident-led meetings.

“A couple of years ago, lots of meetings were taking place and multiple people discussed without clear governance from my organisation, or understanding from partners around multi-agency case management,” says Andy Furphy, a detective superintendent with the Metropolitan Police based in Lewisham. “People were falling into silos and only having access to certain services.”

As a result, processes were simplified between the police and children’s services, with a youth violence and gangs panel being directly followed each week by an overarching missing, exploited and trafficked panel.

Tracking and mapping

Lewisham council has developed a tracker, based on input from the police, children’s and youth offending services, which considers a range of risk factors that feed into professional judgment as to whether a young person is involved in county lines activity. Markers put on individuals have helped map where networks are expanding to, informing joint working with other police forces.

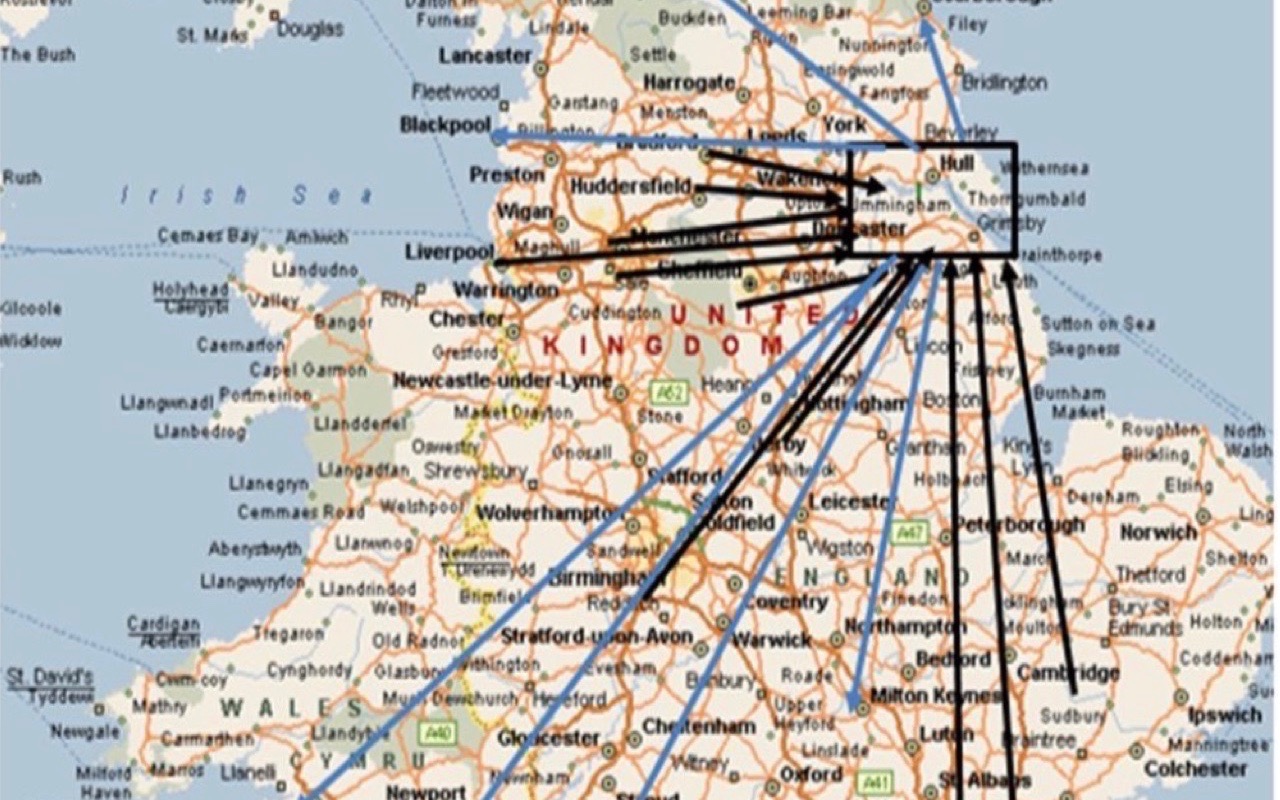

Meanwhile North East Lincolnshire has traced lines coming into it – from Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham and Nottingham – as well mapping 94 local children who have been exploited by associated criminals, who Leivesley says have fully taken over drug dealing activity in the area.

“Sadly, there is an enormous correlation between kids in the alternative education system, looked-after children, and children with multiple indicators of neglect,” she says.

“Children who have adverse childhood indicators and live within certain areas, we can utilise that to predict that they could be at risk of exploitation in later life,” she adds. “We’re hoping that by targeting resource into primary schools in those gateway areas that you will be able to identify vulnerabilities earlier and prevent exploitation happening.”

Prevention and engagement

Effective prevention work is understandably a major focus for these local authorities.

In Southend, the adolescent intervention prevention team, which is co-located with the council’s MASH, has brought together staff from YOS and education backgrounds, including street outreach workers, with a small team of social workers. It works on a four-tiered approach, ranging from CCE awareness campaigns and school workshops to direct work with children on protection plans.

“We’ve realigned several core local authority functions and embedded them in this team,” says Alex Bridge, the service manager responsible for it. “So we deal with children missing from education, conduct return-home interviews for missing children, and undertake truancy sweeps on behalf of schools. We understand these are the most likely children to get into exploitative behaviours, so we try to get onto them early.”

As with North East Lincolnshire and some other areas we speak to, Bridge says the pattern is now increasingly one of local young people being exploited – in Southend, by out-of-towners who can quickly pop over from London.

Southend, which links with fellow unitary authority Thurrock and the surrounding county, has worked with London boroughs to secure criminal behaviour orders (CBOs) banning some individuals from venturing beyond the M25.

Where local children are being exploited, and are at child in need or child protection level, they are allocated two practitioners – one social worker and one early help worker. “The idea is that when children come into [the adolescents’] team they don’t go out – we see kids two or three times a week and having a second worker involved allows for relationship building,” says Bridge. He adds that Southend is fortunate in that many children the council is working with have been engaged at an early stage.

Croydon council is adopting a similar approach. Within its adolescent support teams, the number of social workers has been reduced. Instead, specialist youth workers have been recruited who can both support social workers and work intensively with young people.

“We’re trying to have a combination of approaches to make a difference to children’s lives,” says Hannah Doughty, Croydon’s head of adolescent services, early help and children’s social care. “We want workers who are persistent, will knock on doors to find people, and are able to engage.”

Lived experience

While service setups vary from area to area, all those we speak to here agree on the value of employing, or contracting for, expert workers who know intimately the issues young people they deal with face.

The St Giles Trust, a charity based in south London, has for years delivered specialist support services, including to young people affected by gang violence, largely via practitioners with lived experience. Since 2017 it has been running pilots in London, Kent and South Wales, initially funded by the Home Office, to test approaches to enable young people to disengage from county lines networks. Such moves, which can be fraught with huge danger for them and their families, are not easy to achieve.

“With county lines cases, one distinguishing feature is that you often don’t work with the child at start – they’ve been well groomed and may think they’re having a great time, or that there’s no alternative but to continue,” says Evan Jones, head of community services at the trust.

“We’ve found it’s worth spending time with their mum, and with other professionals involved, assess what’s going on, and then what tends to happen is that the young person seeks help – because horrible things happen so often,” Jones goes on. “It’s not unusual for them to witness a stabbing, be a victim of violence, see an overdose, not get paid for drug run – any number of things can make them reconsider their situation. But unless the right worker is there, they won’t make the jump.”

Within the organisation’s Kent pilot, 31% of the 35 children that received one-to-one support and were still engaged in September had successfully exited county lines activity and were making steps such as getting back into education, Jones says. A further 54% had “made progress but were not home and dry yet”, he adds. “It’s not a big sample but this is the only data out there – it could be an aberration but we are very pleased.”

But Jones argues that such interventions can only bear full fruit in the setting of a whole-system model that addresses both causes and effects of criminal exploitation.

Exploitation in context

Much of the literature that has emerged around child criminal exploitation and county lines activity has referenced contextual safeguarding – an approach developed by Dr Carlene Firmin of the University of Bedfordshire. This is now being piloted at Hackney council and is being eagerly examined by many at the moment in relation to CCE.

Rather than focusing on the family setting, it looks at wider factors, including people, institutions and the physical environment, as locations of potential risk and harm.

“To take you through a full-system response, at the front door where a child is referred, a couple of things may look different,” Firmin explains. “First, if the risks around CCE relate to an extra-familial context, like a school where children are being targeted, or a community space, or linked to an organised crime network or a peer group, those factors would be drawn out explicitly in screening process to help assess risk.

“It wouldn’t just be parenting capacity and risk in family that would be assessed at that point, to get a sense of tier or threshold for support,” she adds. “It would be assessing what we know around extra-familial factors and how that helps us understand how vulnerable that child is.”

Unlike with conventional safeguarding arrangements, a referral or assessment may also be conducted on a context. So, for instance, a school could be evaluated to decide whether an intervention plan was required for it in order to safeguard children.

“You may have an assessment of a location or group, alongside that of the child and family, and the family would be given far more space to talk through how extra-familial risks are impacting on their capacity to parent,” Firmin says. An intervention plan, she adds, could include measures to address the physical design of spaces where young people are groomed, as well as work to either disrupt or strengthen peer and community networks depending on whether they are sites of safety or risk.

In Hackney, some unusual partners have been recruited to increase local safeguarding capacity. “One takeaway would give out free chips or chicken [when tensions were rising between groups of young people] – it was actually quite effective in dissipating things in the short term – and letting children use the phone,” says Lisa Aldridge, Hackney’s head of safeguarding and learning. “We built on that, saying, ‘here is the out-of-hours number, these are the signs to look for, here’s what you can do if you’re worried about young people’.”

Discussing social work practice, Aldridge adds that practitioners are being encouraged to think in various ways about children’s context outside the family. “It might, for example, be doing safety mapping with a young person who is experiencing harm on the way to school – mapping where they feel safe/unsafe, how they can navigate the route, understanding more about their peer group, who are the biggest influences in their life.”

A toolkit evaluating Hackney’s pilot and looking at how to implement a full-system approach to contextual safeguarding is due to be published in March 2019.

But the approach is in its infancy and will take time to become part of children’s services practice – with Firmin cautioning against it being “diluted” by premature or ill-thought out adoption.

Several interviewees also mention the ‘public health model’ used in Glasgow to tackle the root causes of youth violence, which saw knife crime significantly cut via a combination of enforcement, understanding of risks and traumas faced in children’s early lives that make them vulnerable to exploitation, and support towards exit routes. A version of the approach is being promoted by the mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, with a new ‘Violence Reduction Unit’ launched in September 2018.

Back in North East Lincolnshire, Leivesley and her colleagues now routinely train practitioners, ranging from social workers to A&E nurses, in how to identify and work with children affected by county lines exploitation. They are also recruiting to a new team called GRAFT (Gaining Respect and Finding Trust), which will include a range of practitioners, including a CAMHS therapist, and will work intensively with criminally exploited children, on their terms, for as long as they need.

“Our practitioners do not stand on a pedestal above these kids telling what they need to do,” she says. “They are exploited, they have no control – people control them. We need to offer them opportunities to take back control.”

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  ‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services

‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services  How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence

How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence  How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families

How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

The drug situation is endemic, and the exploitation will sadly continue until a fresh view of the legal use of drugs is considered.

All social workers need to go the extra mile to really get to grips with what is happening to kids and help them to feel safe or provide safe mentors that they can talk to about what is going on for them. They will be so scared and fearful of what might happen if they tell. They may need to be moved away to places of safety where they can trust that these abusers cannot get to them.

Give us smaller case loads and less repetitive paper work that could be completed by a typist and we would gladly go the extra mile each day .. gaining trust and getting Alongside these children and young people , sometimes over years is the best way to make a difference ! Case loads and pressures are relentless and don’t allow this . I’m a looked after children’s social worker believe me !!

An excellent report and a much needed focus on young people being victims not criminals. We are a society that has ceased to fund youth services for ten years and we now have a margalused and youth population that are viewed as demons. Instead we need to support and inspire our precious next generation. We are losing too many young people too soon.

My god absolutely

In total agreement

Youth /parent worker sutton surrey

Brilliant article highlighting the truth of what is happening with our young people and the increase in violent crime. What happens next is everyone’s concern. They saw this coming since 2015 and the evidence is clear, nothing was done to prevent it getting worse. I have been working with vulnerable children and young people for over 10 years now and left my job as a project officer for a local council to undertake a counselling qualification and set up.my own organisation to see if I can help them. It’s time to stop talking and implement early intervention in all local authorities NOW!! Mauva Johnson-Jones, Director of Precious Moments & Health Ltd.

Hi Maura is setting up your own company an easy task. I am a SW and have just started down the route of counselling to change career in the next few years. I would be grateful for any guidance. Thank you