What would most improve child protection in England?

- Lower caseloads for child protection social workers (63%, 701 Votes)

- Setting up expert multi-agency units to handle all child protection cases (16%, 184 Votes)

- Improved multi-agency working without setting up expert units (6%, 69 Votes)

- Improved practice in the police, health and/or other agencies (5%, 61 Votes)

- Improved training and supervision for child protection social workers (5%, 53 Votes)

- Ring-fencing child protection casework for "expert" social workers (5%, 52 Votes)

Total Voters: 1,120

“Systemically flawed” joint working undermined agencies’ ability to uncover the abuse of Arthur Labinjo-Hughes in the weeks before his murder.

That was the damning conclusion from the Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel’s review into the killing of the six-year-old by his stepmother, Emma Tustin, and father, Thomas Hughes, in Solihull

The panel cited as a critical problem Solihull council’s failure to convene a multi-agency strategy meeting when Arthur’s paternal grandmother reported bruising on his back – in April 2020, two months before his death.

Instead, the children’s social care service adopted a “single agency” approach in carrying out a home visit, which left social workers strongly reliant on self-reports by Tustin and Hughes, without the ability to triangulate these with other information. It also prevented professionals from challenging their own biases about the family, including the belief that Hughes was a protective factor for Arthur.

After the panel released its report, the chief executive of Solihull Council, Nick Page, revealed that social workers in the borough had faced such abuse that some had had to leave their homes, following Tustin and Hughes’s trial, which concluded in December 2021.

‘Systemic flaw’

Giving its verdict on Arthur’s case, the panel said: “Our conclusion is that a pivotal dynamic underpinning many of these practice issues was a systemic flaw in the quality of multi-agency working. “There was an overreliance on single agency processes with superficial joint working and joint decision making. This had very significant consequences.”

On the back of its reviews into the murders of Arthur and 16-month-old Star Hobson, in Bradford, the panel called for the creation of multi-agency expert child protection units – to tackle the two key failings it identified in both cases: inadequate joint working and a need for sharper child protection skills and expertise.

Related articles

After his parents separated in 2015, Arthur lived with his mother, Olivia, during which time he was assessed twice by Birmingham children’s services, firstly, after Olivia’s partner assaulted her in 2018, and then after she was arrested for killing her partner, in February 2019. She was subsequently convicted of manslaughter and imprisoned.

Father assessed as ‘protective factor’

Arthur moved in with Hughes, and the Birmingham social worker allocated the second assessment found him to be a protective father and that Arthur had positive family support from his paternal grandparents, so the case was closed.

The review found Hughes remained a protective factor until he began a relationship with Tustin in autumn 2019. She had a long history of involvement with children’s social care and was also known to other agencies, including mental health.

Arthur was subsequently seen by Camhs in March 2020, after Hughes reported increasing concerns about his emotional wellbeing and behaviour, but it did not offer him a service. The review found this was surprising given that the assessment had found Arthur was experiencing loss and confusion following his mum’s arrest, and had witnessed and experienced abuse at home.

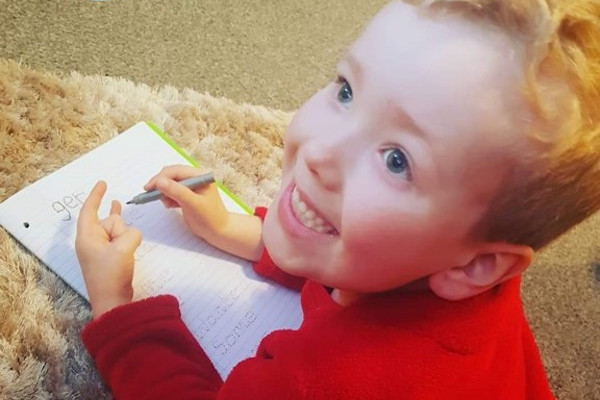

Arthur Labinjo-Hughes (credit: West Midlands Police)

‘Missed opportunity’

The review said this was a “missed opportunity” to meet his needs, with the Birmingham and Solihull Mental Health Foundation Trust reflecting that the assessment was of limited quality and he should have met the eligibility criteria for a service in relation to wellbeing and anger management.

In the same month, a Cafcass family court adviser conducted a section 7 welfare assessment, in response to Arthur’s mother’s request to re-establish contact after Hughes had stopped it.

The review found the assessment, which recommended only indirect contact between Arthur and his mother, was done in accordance with the court order, but that wider liaison with Camhs and Arthur’s maternal family might have led to a better understanding of his needs.

Hughes and Arthur moved in with Tustin, and two of her four children, at the start of the first coronavirus lockdown in March 2020. As Arthur was not classified as vulnerable, he stopped attending school.

‘Critical fortnight’

The review identified a critical fortnight for Arthur in April 2020. On 14 April, Hughes and Arthur went to stay with Hughes’s parents, after an argument with Tustin, allegedly linked to a fight between Arthur and Tustin’s son.

On 15 April, Hughes reported Tustin missing to the police, saying she had also expressed suicidal thoughts. When she was found by street triage team, including a nurse and a police officer, she declined a referral back to the community mental health team, but reported that Arthur had punched her son, prompting an argument with Hughes, in which he had pushed her son with his elbow.

The review found that both the alleged assault by Hughes on Tustin’s son and Tustin’s mental health should have prompted a referral to Solihull multi-agency safeguarding hub (MASH), in the context of the risks to the children in the household.

The police officer charged with locating Tustin when she went missing then visited Hughes’s parents’ house and found Arthur looking fit and healthy and observed Hughes to be a concerned and caring father. The same officer had broken into Tustin’s home, when looking for her, and found it clean and tidy, with age-appropriate toys – observations that turned out to be important in framing subsequent responses.

Reported bruising

On 16 April, Arthur’s paternal grandmother reported bruising to Arthur’s back to Solihull emergency duty team, and said she had taken photos. Arthur and Hughes said these had been inflicted by Tustin’s son, but his grandmother was concerned that Tustin was responsible. On the same day, Arthur and Hughes returned to Tustin’s house, despite “strongly expressed misgivings” from the boy’s grandparents.

The EDT then asked the police to carry out a welfare check. However, the officer who had seen Arthur the previous day said the police had no safeguarding concerns so the force did not carry out the check.

The review said this decision was not appropriate as the grandmother’s report was new information. A visit that evening should have identified the bruising and led to the initiation of child protection procedures.

The decision not to visit was challenged by Arthur’s grandmother, who told the EDT she was not certain that Hughes would protect Arthur if he was at risk. She was assured the MASH would follow up the following day.

However, the MASH followed up with a “threshold visit” – a single agency visit by a duty social worker in situations where a child does not appear to be at immediate risk – despite local guidance requiring a joint investigation in cases of suspicious injury.

Failure to convene strategy meeting

The panel concluded that a multi-agency strategy discussion – which Working Together to Safeguard Children states should be called when there is reasonable cause to suspect significant harm to a child – should have been triggered at this stage. It said the failure to do so “set the tone for subsequent practice weaknesses in responding to the allegations about bruising to Arthur”.

The practitioners conducting the threshold visit said Hughes and Tustin engaged well and, though they saw a faded bruise on Arthur, the review found that it was unlikely they had seen the bruising witnessed and photographed by his grandmother.

The social workers concluded there was not a need for a section 47 enquiry, instead offering Hughes life-story work for Arthur in the context of the trauma he had experienced in the past year.

Couple seeking to ‘mislead and manipulate professionals’

The “limited nature of a threshold visit” meant the practitioners were reliant on self-reports by Tustin and Hughes that Arthur’s injuries, and those of Tustin’s son, were down to fighting between them. Subsequent evidence showed the couple were “seeking to mislead and manipulate professionals” at the time.

Following the visit, the MASH neither informed Arthur’s grandmother of the outcome of her referral, contrary to expected practice, nor the police.

This shaped the police’s responses to concerns about photographed bruising to Arthur from Hughes’s brother and the boy’s maternal grandmother, reported on 18 and 20 April. In both cases, the police said children’s social care was handling the case.

Case closure

The maternal grandmother also contacted the MASH, emailing the photographs to the service on 24 April, which the paternal grandmother confirmed were taken on 16 April.

When a social worker asked Hughes about this, he repeated the explanation that the bruising had come from fighting with Tustin’s son. An assistant team manager subsequently reviewed the photographs and concluded further investigation was not necessary as the children appeared to be safe and well, and the injuries could be consistent with a playfight. Instead, a family support worker would follow up with the offer of life-story work and, if the family consented to work with them, would be able to monitor, and escalate if necessary.

However, on 27 April, Hughes rejected the offer of life-story work and told the family support worker he would speak to the school if he needed further help with Arthur’s behaviour. The case was then closed.

While Hughes subsequently had contact with Arthur’s school and GP over his wellbeing and behaviour, the boy was not seen again by a professional. He died on 17 June 2020 after suffering a fatal head injury, dealt by Tustin.

Key learning

The panel’s key conclusions from the case were that:

- Professionals only had a limited understanding of what life was like for Arthur, with short assessments and visits limiting the opportunity to build trust.

- Practitioners did not always hear Arthur’s voice, relying on his father’s perspective.

- The framing that Hughes was a protective factor was never challenged even when evidence to the contrary – notably his mother’s concern that he would not protect Arthur – emerged.

- Proper consideration was never given to the risks of Arthur going to live with Tustin, despite her long involvement with children’s social care.

- Arthur’s wider family’s views were not listened to and their concerns not taken seriously, despite their many attempts to get agencies to look into what was happening to him.

- The response to the bruising was undermined by the lack of a multi-agency strategy discussion, with the single agency response leaving social workers “to make judgments about evidence of bruising without the relevant professional knowledge, guidance on how reports of injuries are viewed and triangulated, or tools for accurately recording injuries observed”.

The panel added: “The nature of the assessments and decisions that child protection professionals are being asked to make are extremely complex. They cannot do it alone. Robust multi-agency working is critical to the challenging work of uncovering what is really happening to children who are being abused.”

Children in situations of ‘unassessed and unknown risk’

After Tustin and Hughes were jailed for Arthur’s murder and manslaughter, respectively, in December 2021, education secretary Nadhim Zahawi commissioned the panel to review learning from the case, as well as a joint inspection of the multi-agency response to risk in Solihull.

This reported in February 2022, finding that a “significant number” of children were left in situations of “unassessed and unknown risk” because of assessment delays at the front door, themselves the result, in part, of there being insufficient social workers. It also criticised safeguarding partners’ lack of oversight of the MASH.

The inspection report led the DfE to issue Solihull council with an improvement notice, meaning the authority must work with the department’s appointed improvement adviser, Gladys Rhodes White, to tackle the issues identified in the inspection.

‘Social workers forced to leave homes’

In a statement following today’s report, Page reported that one of the council’s improvement advisers had said that child protection social work involved “making a really difficult jigsaw puzzle with some of the pieces missing…while perhaps doing another 15 or 20 at the same time, with pieces missing as well”.

He added: “Being a social worker is one of the most caring, yet hardest vocations to do, and I’m proud that we’ve got expert, dedicated and caring people working with us here.

“But I’ve been concerned over the last six months because the level of abuse and even threats towards them has meant that some have had to leave their own homes, with their families, with their children and with their partners. This can’t be right.

Page said that “now was not the time for blame, but it is most definitely the time for learning and sorting”.

He added that “we need to think long and hard about how we support and help those children and young people live happy and safe lives, how we get better at looking after children”.

Police response

Giving West Midlands Police’s response, assistant chief constable Claire Bell said: “We owe it to Arthur to not miss a single opportunity to learn from what happened to him so we can better protect children in the future.”

She said the force had invested in additional training for officers in relation to safeguarding, including domestic abuse, and was improving the quality of its management systems to enable it to better identify risk.

Bell added: “We know there is still more to do and we are determined to work collectively with partners to act upon the panel’s recommendations and make the changes needed to better safeguard children in the future.”

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  ‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services

‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services  How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence

How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence  How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families

How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

So yet again we hear that the ‘system’ is flawed after a child’s death and agencies will act upon a panel’s recommendations to better safeguard children in the future.

Nothing will change what has sadly happened and maybe it is not right or “not the time” to blame an individual involved with the case but I wonder if the same conclusion would be reached if Arthur had been a ‘vulnerable’ adult and it was a Care Worker and their agency who had missed the signs of bruising and not acted upon concerns raised by the wider family?

Twenty per cent rise in children’s social workers quitting sector last year, suggest government figure” – Community Care article right under the article you responded to.

Here is an excerpt:

“Social workers consistently working over hours

In relation to the drivers of poor retention, researchers were “told consistently that social care practitioners were working well outside of their contracted hours to complete their work, driven by high levels of bureaucracy and caseloads”.

Social workers said their high workloads reduced their ability to do direct work, offer meaningful support to families, think about cases creatively or use their professional judgment, as they ended up following processes instead.

High workloads were linked to the significant levels of administration that practitioners had to carry out – which was taking up 60%-90% of practitioners’ time and leading to several working outside of their working hours.

Participants reported this being driven by a compliance approach to auditing and inspection, risk aversion and anxiety that things can go wrong and NQSWs, in particular, not having the skills or experience to record case notesconcisely.”

I know of social workers who REGULARLY work late into the night to complete court report.

If you don’t see a systemic problem in the this, I certainly do!!

Anne- You have hit the nail on the head.

Do Social Workers honestly believe they are the only profession that work outside of contracted hours and have to do more administration work today than previously??? It appears unbelievably so but this is the case for lots of people in all professions today and some of those do work with the most vulnerable people in society and on a lot less wage than Social Workers. It is time to stop whining, making excuses and to take accountability for what the public know was bad practice and a lack of duty to care and safeguard a child not once but over a period of time in this case, a child who was already known to Children’s Services.

If others do to, than it must be ok. That’s your answer to the problem, is it? Ignore and continue as we are, regardless of the fact it clearly isn’t working and SWs are leaving the profession in droves. Well, if that attitude doesn’t have children’s best interest at heart… :-/

You are, by the way, part of the society and system that deems it acceptable to chronically underfund services for the most vulnerable children in the country – not just in child protection but also in mental health, long-term care and leaving care – let alone a society that finds it acceptable that private companies make money on the backs of those children and young people. I

Perhaps you’d like to raise the “whining” issue with those kids…