By Tim Spencer-Lane

The issue in this case was which of two local authorities was responsible for providing and paying for “aftercare services” under section 117 of the Mental Health Act 1983 (“MHA”) for a particular individual.

What does section 117 say?

Section 117 places a duty on health authorities and local social services authorities to provide aftercare services for people who have left hospital following compulsory detention for treatment for mental disorder under the MHA (for example, under section 3).

The duty is placed on the authorities in whose area the person concerned was ordinarily resident “immediately before” being detained. The complication in this case – which is common in practice – was that following their first detention, the person was placed in another local authority area and eventually detained for a second time.

Why did the dispute arise?

It had been widely understood that the correct approach in such cases, was to determine the person’s ordinary residence by reference to where they were living immediately before their last detention.

This interpretation is supported by the care and support statutory guidance under the Care Act 2014, issued by the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). This sets out that when a person in receipt of section 117 services is moved to new area and detained again under section 3, the new social services authority will become responsible for their aftercare (paragraph 19.64).

However, the DHSC changed its mind and challenged its own guidance. In 2020, it published five decisions which adopted a radically different approach to determining ordinary residence for the purposes of section 117 (one of which was the Worcestershire case).

These determinations stated that the correct approach in such cases was to determine the person’s ordinary residence by reference to where they were living immediately before their first detention.

In addition, the determinations set out that so called “deeming rules” – which mean that if a person is placed by a council into another local authority’s area, the first authority retains responsibility for their care – should be read into section 117.

The facts of the Worcestershire case

This case involved a woman (“JG”) who had treatment-resistant schizoaffective disorder. She lived in a property in Worcestershire County Council’s area and was detained under section 3 of the MHA.

It was not in dispute that, at that point, JG was ordinarily resident in Worcestershire and therefore it had responsibility for her section 117 aftercare.

She was assessed as lacking capacity to decide where to live. Following consultation with her daughter and others involved in JG’s care, a decision was made that it would be in JG’s best interests for her to reside in a care home close to where her daughter lived, in Swindon Borough Council’s area. This was arranged and funded by Worcestershire.

A year later, JG was detained again under the MHA (initially under section 2, and then under section 3). A dispute arose between Worcestershire and Swindon as to where JG was ordinarily resident immediately before her second detention. The dispute was referred to the secretary of state for health and social care.

Originally, the secretary of state determined that JG was ordinarily resident in Swindon at the time of her second detention and, therefore, it was responsible for her section 117 aftercare. However, this decision was reversed on review. The secretary of state determined that JG had been ordinarily resident in Worcestershire immediately prior to the first detention and this responsibility did not end when she was detained a second time.

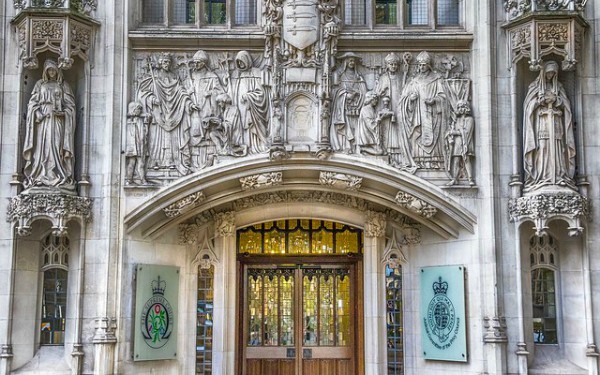

Worcestershire successfully challenged this determination in the High Court. The judge ([2021] EWHC 682 (Admin)) found that, following the second discharge, JG had been ordinarily resident in Swindon. However, this decision was overturned by the Court of Appeal ([2021] EWCA Civ 1957). That decision was appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court decision

Lord Hamblen and Lord Leggatt gave the judgment (with which all the other members of the court agreed).

Further legal guidance

Tim has done a more detailed analysis of the Supreme Court’s judgment for Community Care Inform Adults, which anyone with a subscription can access.

Tim has done a more detailed analysis of the Supreme Court’s judgment for Community Care Inform Adults, which anyone with a subscription can access.

When does the section 117 duty cease?

It was not in dispute that, following the first discharge, the duty to provide aftercare services for JG was owed by Worcestershire and that Worcestershire did not at any point take a decision that JG was no longer in need of such services.

But importantly, it was also accepted that Parliament cannot have contemplated that “two parallel duties, owed by two different local authorities, to provide aftercare services for the same individual should exist at the same time”. This would be a recipe for disputes between authorities and risk “logistical chaos”.

Lord Hamblen and Lord Leggatt held that the best explanation of why concurrent duties do not arise was provided by reference to section 117(1). This sets out that the section 117 duty is triggered when a person ceases to be detained and leaves hospital.

Lord Hamblen and Lord Leggatt reasoned that if a person has been re-detained in hospital for treatment, the criteria in section 117(1) are no longer met (ie that individual is no longer a person who has ceased to be detained and has left hospital). Thus, upon such detention an individual ceases to be a “person to whom [section 117] applies”.

The judges argued that this interpretation was grounded in the language and purpose of section 117, especially the very concept of “aftercare”. Section 117 defines the purpose of “aftercare services” as being, “reducing the risk of a deterioration of the person’s mental condition (and, accordingly, reducing the risk of the person requiring admission to a hospital again for treatment for mental disorder)”.

That purpose was only capable of being fulfilled if the person concerned was not currently detained in a hospital for treatment for mental disorder.

It was therefore concluded that the duty to provide aftercare services automatically ceases if and when the person concerned is detained for treatment under the MHA. In this case, therefore, Worcestershire’s duty to provide aftercare services for JG ended upon her second detention. When she was discharged, a new duty to provide aftercare services arose.

Which local authority owed that duty is determined by section 117(3) and depends on where JG was ordinarily resident immediately before the second detention.

Ordinary residence

The secretary of state argued that deeming rules should be read into section 117, based on the Supreme Court decision in R (Cornwall Council) v Secretary of State for Health [2015] UKSC 46.

This held that, when a young person turns 18 and transitions from children’s legislation to adult social care legislation, their ordinary residence will remain with the local authority in whose area they were ordinarily resident immediately before turning 18. This was largely to avoid the “undesirable” and “adverse consequences” of having a hiatus between the relevant legislation.

However, the secretary of state’s argument was rejected by Lord Hamblen and Lord Leggatt. This was because the MHA does not contain deeming rules.. It was also clear that, during the passage of the Care Act 2014, which amended section 117 by adding reference to “ordinary residence”, Parliament had deliberately chosen not to apply deeming rules to section 117.

It was, therefore, concluded that the words “is ordinarily resident” must be given their usual meaning, so that JG was ordinarily resident in Swindon immediately before her second detention. Thus, following the second discharge, Swindon, and not Worcestershire, had the duty to provide aftercare services.

What does the judgment mean for local authorities?

The effect of this judgment is that the law on section 117 and ordinary residence (as set out in the care and support statutory guidance) has not changed.

Ordinary residence should be determined by reference to where the person was living immediately before their last detention. It has also been confirmed that section 117 does not contain deeming rules and ordinary residence should be given its natural meaning.

The DHSC had published a ‘guidance note’ setting out that, pending the outcome of the legal proceedings, it would stay the determination of new ordinary residence disputes which concern section 117 and raise issues similar to those in the Worcestershire case.

These ordinary residence disputes will now need to be determined by the secretary of state in the light of the Supreme Court judgment.

What issues might arise in the future?

It is interesting that Lord Hamblen and Lord Leggatt appear to have argued that any best interests decision to place a person in an area means that the person has voluntarily adopted that residence and is hence ordinarily resident there (paragraph 58 of the judgment).

This is at odds with the care and support statutory guidance, which essentially sets out that a fact-based approach should be adopted to ordinary residence in such cases (see, for example, paragraph 19.32 of the guidance).

Whist the comments of Lord Hamblen and Lord Leggatt appear to have been obiter, which means they do not set a legal precedent, they could lead to confusion on the ground and generate future legal challenges.

Finally, it should be noted that the government has published a draft bill to amend the MHA, which includes provisions that would insert the deeming rules from the Children Act 1989 and Care Act 2014 into section 117 (clause 39).

Therefore, if the bill is passed, the Supreme Court’s decision may be reversed in the future.

Tim Spencer-Lane is a lawyer specialising in adult social care, mental health and mental capacity, and is legal editor of Community Care Inform.

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  ‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services

‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services  How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence

How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence  How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families

How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

So… in the meantime we have chaos with OR again for anyone in hospital that was re-detained from a different LA area.

I imagine it will be important in the future to be clear when exactly the s117 duty is triggered. Which I think is ‘upon discharge’ not upon being placed on a section 3.

Great news that Hancocks ridiculous meddling with S117 has been overturned. but does this mean that LAs will now be able to transfer existing aftercare arrangements to the LA where the person was last detained?

This does make a lot of sense – assuming the majority of people are likely to want to stay in the area they lived in immediately prior to detention, these LA/ICBs are the experts in the provisions in their local area. Having people potentially based hundreds of miles away and with no local knowledge trying to source appropriate provision is both a logistical nightmare and not in the best interests of the individual.

Lay person here subjected to s3 out of area placement in the past and extremely worried as an older person that MH Trusts and LA will be given a green light to ship me hundreds of miles away. Then say I live there because lose my home here whilst sectioned so go into some form of temp accommodation in a area no connection with. Same diagnosis as the pt here

Does this decision stop that from happening even temporarily?

Know so many who got caught in these arguments so lost safe accommodation became homeless. It is extremely stressful