*Names have been changed

Here, they talk to you like you’re a human being and not an addict, not somebody who’s a lowlife.”

Sitting holding *Freddie, her sleeping three-month-old baby, *Megan doesn’t miss a beat when asked what it is about Jasmine Mother’s Recovery that, in her words, “saved her life” – and Freddie’s.

It’s the approach of the staff at this rehab centre that Megan credits with helping her detox and stay clean, and grow her confidence in herself and her parenting.

At Jasmine – part of Plymouth-based charity Trevi – Megan feels she’s been treated as someone worthy of support rather than “outcasted” like she’d been in the past.

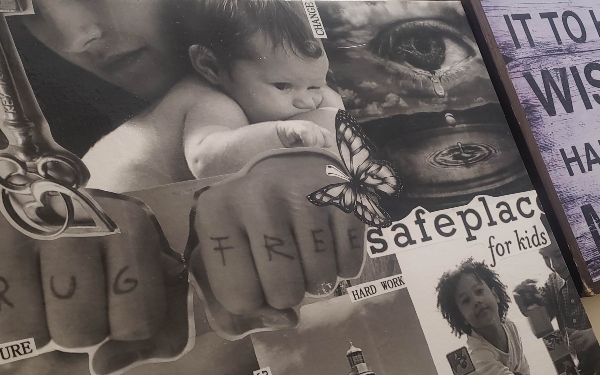

A ‘lifesaving’ service

Many of the women we meet here use the word ‘lifesaving’, and it isn’t a figure of speech. If she hadn’t been “pretty much mandated” to come here in care proceedings, or have her child taken into foster care, “I’d be dead or on the streets somewhere or in hospital,” Megan says.

At points in her pregnancy, she’d been using drugs every week and was hospitalised a number of times due to suicide attempts, she explains.

Now, after two months of Jasmine’s treatment programme, and with another four weeks to go, she is hoping to return home with Freddie, subject to a successful parenting assessment.

She hopes her six-year-old daughter – who was removed after a previous relationship breakdown and period of mental ill health led to her alcohol and drug misuse – will also be returned to her care.

The only provision of its kind

Bedroom at Jasmine Mother’s Recovery. Photo: Trevi

Jasmine is the only rehab provision in the country specifically for mothers where they can stay with their children, with the goal that on leaving, as well as staying abstinent, they can keep their children.

Last year, 83% of women referred here successfully detoxed, and eight out of 10 children were able to remain with their mother after leaving.

Jasmine accepts referrals from across the UK. As some residents tell me, distance from the town where you are known to dealers – and/or from violent or co-dependent relationships – can play a part in helping someone establish a ‘clean’ life.

When Community Care visited Trevi House, as Jasmine was then called, in 2017, it was at half occupancy with no waiting list. CEO Hannah Shead, who has been here since 2011, says it is currently full but demand fluctuates due to a lack of awareness that the service exists, and the funding model meaning it is sometimes perceived as only for very extreme cases.

This is despite money spent at this point potentially saving local authorities thousands in the long run by keeping a child out of care.

For most placements, the mother and child are funded separately by adults’ and children’s services. Hannah says that, currently, funding from adults’ services is a bit easier to come by, while it is more of a challenge for cash-strapped children’s services.

Women often fight to come here or it is ordered by the court, frequently, but not always, by family drug and alcohol court (FDAC) judges.

“We’re seen as a really niche response, whereas actually I think there should be somewhere like this in every region,” she adds.

Tension between needs of parents and children

Hannah acknowledges that Jasmine sits at a point of tension: “In our world, people are often either aligned with the needs of the adult or they’re aligned with the needs of the child. And we try and work with both and that isn’t always easy.”

Women have to want to work on their recovery from addiction, not just be focused on wanting to keep their child, I learn from Vicky, a former resident back for a visit today.

Generally, a rigorous assessment and admissions process means that only women whom staff believe will benefit from the service come here.

Occasionally, Vicky says, someone would resist the treatment programme, which could disrupt the house dynamic. In severe cases, placements have to be ended, which is devastating for all involved.

An inescapable focus on child safeguarding

In the garden at Jasmine Mother’s Recovery. Photo: Community Care

The centre’s child safeguarding function is another area of potential complexity. Around 90% of the children here are under interim care orders.

While, as Megan describes, the atmosphere is warm and family-like – the communal dining area the women eat round while feeding their babies feels like the heart of the place – small reminders that their parenting is continually being observed are inescapable.

A security gate protects access to the centre, while CCTV cameras cover all the bedrooms and communal areas. Baby monitors are in constant use for mothers to monitor their child’s welfare, and for staff to observe them. Care plans and risk management plans for each family are reviewed at least once a week in Jasmine’s multi-disciplinary team meetings.

And the child’s placing social worker or local authority duty team are informed immediately of any safeguarding incidents.

*Mia has a two-year-old, one of the oldest children currently at Jasmine. She would love to take him to the park but this could only be done on a planned supervised trip.

This is the one of the few indications we hear from the women that the set-up is challenging. Another is that being around a lot of other women can be hard for some residents. Mostly though, the talk is of opportunity and being given a chance to show that they can parent.

The link between having a child removed and worsening addiction

Shona, the therapist, runs different groups with the women every day, with a focus on trauma and recovery. Women also receive one-to-one counselling.

Shona lets Trevi patron, Jenny Molloy, and me sit in on today’s group. Jenny asks the women who want to speak to tell us how they came to be here, and their experiences with social workers.

Megan is not the only one who has had a child removed previously. The experience of a removal triggering or worsening drug use and addiction is mentioned by many.

*Selena is in Jasmine with her daughter. She calls herself an alcoholic and says she’s dabbled in other drugs.

A few years ago, when her older child was born, she was in an abusive relationship. She went to a mother and baby foster placement and would secretly take her son to visit her then partner “because I was trying to build a family and I thought he loved me”.

But when she returned to living with her partner she couldn’t cope with him “not being what he needed to be for me and my son” and started drinking again. This led to her son being taken into care; he is now looked after by her family.

After my son was removed from me, my life just went so much worse. This structure was removed from my life.”

“I wasn’t getting up and bathing my son every morning,” Selena continues. “I wasn’t changing him, I had no routine to put him to bed…I used to just stand out on the street every night and drink with my children’s dads and we’d beat each other up. And then I got pregnant again with my daughter.”

The group work lodge, children’s play area and garden at Jasmine Mother’s Recovery. Photo: Community Care

*Caitlin’s baby, *Aimee, is eight months old. Aimee was fostered for the first few months of her life and Caitlin could only see her at a contact centre before they were able to come to Jasmine.

She says her drinking was “quite out of control” at the time and she used heroin during her pregnancy. She has completed a detox from methadone at Jasmine and Jenny tells her she looks great, glowing.

Caitlin describes how unsupported she felt when she was in a violent relationship. Her older child was taken into care soon after starting primary school.

“He was turning up late, he had holes in his socks…trivial things. But within two weeks of them getting involved, he was taken out of my care,” she says. “I just spiralled. I wasn’t getting the support I needed.

“Few years later, I got raped quite badly, and [the perpetrator got found] not guilty,” she adds. “And that’s when I realised I was actually addicted to heroin.”

Caitlin says she dislikes the terminology that is often used and the “boxes or brackets we’re put into”.

“Personally I’d rather have the stigma of being an addict, like substance misuse, rather than neglect. We made a few mistakes but it’s because of our addiction, not because we wanted to hurt our children.”

For Community Care Inform’s Learn on the Go podcast, Jenny Molloy – Trevi patron, author, trainer and care leaver – recorded conversations with women to share learning with social workers. Freedom Programme facilitator Helen and former residents Vicky and Hannah discuss what they would like professionals to understand and do to support mothers, and what made for both positive and negative experiences with social workers for them.

Sharing experiences with other women who have been through something similar is a key part of the therapeutic process at Jasmine. Megan tells me she used to feel there was something wrong with her.

“Obviously doing the mistakes that I did when I was pregnant and that feeling of like, ‘why am I like this? No one else is’. I was beating myself up over it. But coming here, I’ve realised that there’s other women out there with similar stories and that we are not bad people.”

We’re not bad mums.”

Everyone’s story is different and personal. But common experiences come up again and again – as well as abusive relationships and children removed, the sense that support to overcome problematic drug and alcohol use and be a good, safe parent is hard to come by.

Feeling judged and fearful of social workers

It’s uncomfortable being from Community Care in an environment where almost everyone says they have felt, at best, judged by social workers and constantly fearful of their perceived power to take their children away.

At worst, when they trusted, did what they believed was expected of them or asked for help, they felt betrayed that the ‘goalposts moved’, most often with care proceedings being initiated.

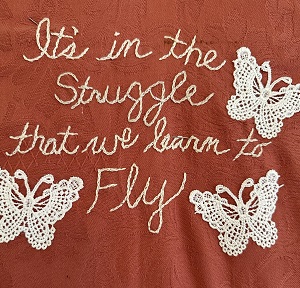

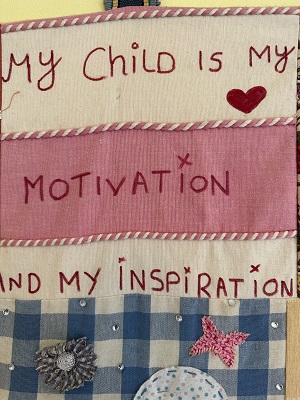

Wall hanging made by Jasmine resident. Photo: Community Care

Tammy was a resident four years ago and now works for Trevi’s Spark project, which supports multiply disadvantaged women who are experiencing abuse, and volunteers as an assertive outreach worker.

She tells me that, before coming here, she moved hundreds of miles across the country to go to a women’s refuge in an area where she knew nobody.

“I’ve done what they’d asked me to do…All through my pregnancy they said they had no plans for removing my child, that she would be going onto a child in need plan.

“Then, when she was a couple of days old, I had a social worker at the hospital saying: ‘We’re going to be taking you to court on Monday to remove your child. We’re gonna let you have contact three times a week for an hour and a half at a time.’”

Instead, the child’s guardian suggested Jasmine and the court ordered her to come here. Tammy says she felt anxious the whole time that her baby could be removed without warning.

“If I was in a [therapy] group and knowing that a social worker was going to turn up, I’d tell the nursery staff: don’t let them get anywhere near my baby, thinking that while I was in group, she was gonna do a runner with my child.

“I was being reassured that I was doing the right things and I know she couldn’t have done that. But at the time, that was how I felt.”

I was literally petrified until the day I actually walked out of that gate with my baby.”

The shared lounge at Jasmine Mother’s Recovery. Photo: Trevi

Selena says: “They tell you to be open and honest. But you go to them for support, and they use that against you. You can’t say anything. If you’re lying, you’re bad. And then if you’re honest, you’re bad too.”

Shona, the therapist, tells me that it is a “huge” betrayal of trust when someone does overcome the shame of using in pregnancy and asks for support, but then feels it is used against them.

“And there’s so much about that then affects their recovery. I don’t think there’s one woman that I’ve met here who hasn’t had that happen to them.”

‘She worked with me, not against me’

While there is fear and anger, many of the women recall good experiences with social workers too.

What characterises positive experiences with social services?

Megan says her current social worker, “seems to have my back a bit …She’s very understanding – she’s quick to give me credit and praise, which you don’t necessarily normally hear.”

“Getting to know the family, not just reading it on paper,” says Helen, a former resident who now facilitates the Freedom Programme here, supporting women to understand domestic abuse and have healthier relationships.

On paper, I look terrible. There was a lot of crap in my past….It’s about understanding people’s past,” she continues.

It’s being that person that goes that extra mile for that family, because then you will get that extra mile back.”

Helen says she sometimes feels professionals have made their mind up about women.

“You can see the hurdles they’re putting in their way. With the good ones, they’re trying to knock down hurdles and really see what’s going on: ‘What does this family really need? How can I help? What resources can I put in place for this woman? And these children. Because my ethos is: if mum’s OK, child’s OK.’”

Vicky puts it straightforwardly: “you’ve got to be kind”. “The best social worker I ever had showed me kindness I’d never seen. She worked with me, not against me. She was very transparent.”

Vicky says newer social workers seem “more open, more receptive to women – which I think is making a massive difference, but we’re not there yet.”

Staff and residents mention wanting social workers to have more training about addiction, both its links with trauma and the physical effects.

“I was told to just stop drinking”, Selena says. “That could have killed me.”

They are also keen to share understanding of domestic abuse, especially why people don’t leave abusive partners.

‘It was not my fault but I was blamed’

We recorded another episode of Learn on the Go at Jasmine, where Jenny Molloy spoke to Helen, Tammy and Lisa, all survivors of abusive relationships, to hear what they would like professionals to understand about domestic abuse. CC Inform subscribers can find the episode, supporting resources and a full transcript here. You can also listen to the episode here, or find and subscribe to Learn on the Go on Apple Podcasts, Spotify and Google podcasts.

Women who are not in abusive relationships may face different challenges if they have a partner who is in active addiction.

Megan explains that her social worker is also trying to help her partner get into rehab: “When there’s two addicts living under the same roof, one of them’s more likely to relapse than the other and bring the other one down.”

Relocating

While some women are looking forward to going back to homes that are waiting for them, Jasmine supports others who want, need or are encouraged by professionals to relocate to Plymouth.

Returning to the town where you were in active addiction carries a risk of relapse. Caitlin is getting support to find somewhere to live in Plymouth “cos I can’t really go back to all the users and stuff where I’m from. They’re all hanging around outside rehabs waiting for you to relapse so it’s not great.”

Wall hanging made by Jasmine residents. Photo: Community Care

If families stay in Plymouth, women can continue attending the same Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), Drug Addicts Anonymous (DAA) and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) meetings they went to while at Jasmine and benefit from Trevi’s Sunflower Centre, a therapeutic service for women with complex needs, including addictions and domestic abuse.

Currently, most women are funded for 12 weeks. After that, local authorities are keen to see women’s ability to look after their children in the community.

While there’s an understanding that funding is tight, staff and many of the mothers say 12 weeks is not long enough to simultaneously detox, go through the therapeutic programme and learn parenting skills. The best results often come when women have longer.

While clearly women want to complete the programme, know whether they can keep their child and move on, I wonder if it’s also daunting to leave somewhere that offers safety, community and a rare experience of feeling supported.

Megan laughs that she’d almost like to live here and is a bit nervous about leaving.

“Obviously just the whole thought of relapsing. Because it’s always in my head, as an addict, it’s always there. But because of the groups and things [here], it’s taught me the techniques I need to prevent that. And it really does, because it’s consistent, it’s every single day.

“Every time I think about using or going back to that, it’s flip and then switch and I do it subconsciously now, so it just goes away. And it installs a fear in you as well that if I do it again, I’m going to lose absolutely everything and I will not have an opportunity to come back here again.”

Megan knows that when she leaves she will have the number of a family support worker from Jasmine and be able to have FaceTime calls.

Does she think she’ll be one of the people who comes back to visit? “Definitely,” she says.

I’ll bring him back when he’s older and be like, look, this is our journey. This is where mum brought you. This place, everyone here, is the reason why we’re together.

Starting life again

Before we leave, Helen has arranged for us to speak on the phone to Hayley, who left Jasmine two weeks ago with her son. We can’t see her face, but the positivity, strength and life in her voice are palpable. Hayley remembers that she didn’t want help at first.

Wall decoration at Jasmine Mother’s Recovery. Photo: Community Care

“I had to reach my low – I couldn’t get any lower – for me to pick myself up,” she says.

Hayley was here for 16 weeks and adds: “It was only the last few weeks of me being here that I feel normal. Like for the past few weeks, I wake up every single morning full of life. I don’t feel ill, I don’t feel groggy. I’m able to see to my son without feeling like shit. I feel amazing.”

She credits Jasmine with helping her to be a mum and also find her own identity, even down to what food and music she likes.

“I literally get to start my life again and figure out what it is I like. I get to do it all from fresh. Clean.

“I never used to see a future. Now you’re asking me about my future and I do. A happy life, a clean life with my boys… I can see it. And I’m jumping in with both hands.”

Learning from lived experiences

Community Care Inform licence-holders can read longer versions of Selena, Caitlin and Tammy’s stories in their own words here on CC Inform. A short video from Jenny Molloy is included to support individual practitioners and groups reflect on what they might take into their practice from hearing these experiences and the messages women want to give professionals.

Community Care Inform licence-holders can read longer versions of Selena, Caitlin and Tammy’s stories in their own words here on CC Inform. A short video from Jenny Molloy is included to support individual practitioners and groups reflect on what they might take into their practice from hearing these experiences and the messages women want to give professionals.

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  ‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services

‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services  How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence

How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence  How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families

How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Glad to read that women are getting support as opposed to automatic condemnation. Sometimes I think that Local Authority Social Work has lost its way with readily looking to remove children. Best wishes to all at the project