When speaking to Elaine James, her passion for upholding the rights of people with learning disabilities is almost infectious.

This is also evident in her accomplishments as the head of service for learning disabilities and preparation for adulthood at Bradford council.

In her time there, she has been instrumental in minimising long-term detentions of people with learning disabilities under the Mental Health Act 1983.

And last year, she was named the social justice advocate of the year at the Social Worker of the Year Awards for her work championing the rights of people with learning disabilities to vote.

Social Worker of the Year Awards judges said she has significantly increased the likelihood of people participating in an election through her work on the Promote the Vote initiative.

Speaking to Community Care, Elaine opened up about her biggest influences, misconceptions about supporting people with learning disabilities and how leaders can help social workers facilitate change.

Can you tell me about your work with Promote the Vote?

We started Promote the Vote in 2015, to support adults with learning disabilities to vote.

If you can own your own life, then you have to deeply believe that you have a right to describe how your life should be. Nowhere is that more compromised than with young people and adults with learning disabilities. Their view is questioned because of a label that was put on them.

I felt strongly that our role as social workers was to look at what’s the biggest decision that somebody can be involved with. Well, there’s no bigger decision than who gets to run the country.

You can register to vote from 17 and that’s something that marks a passage from being a child. As a child, you have a bedtime. As an adult, you get to vote.

With colleagues’ help, I’ve gathered evidence to show that, when social workers talk to these people about their rights, they’re more likely to do something about it because they feel they’ve got support.

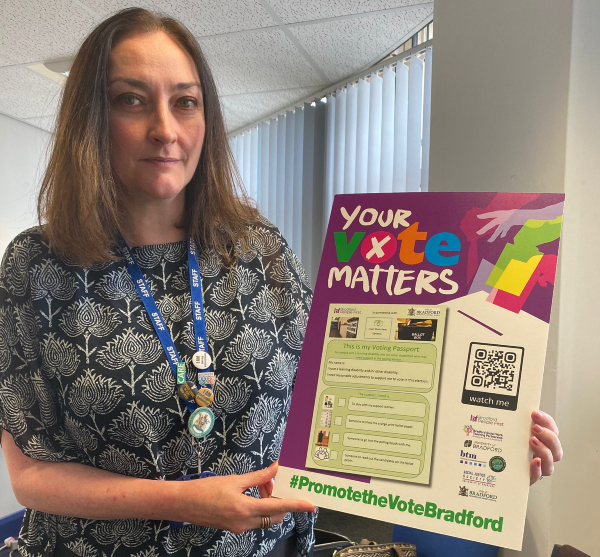

Elaine James promoting the right to vote in Bradford

In the services that I manage now, we’ve worked with local user groups who were campaigning about this issue long before we woke up to it. We now make it a central part of transition planning that we support a young person to understand their right to register from 17, what reasonable adjustments they can lawfully request and how to gain a local voter passport [setting out their voting needs].

There are amazing things you can do that you don’t know you can do – right up to supporting people in the polling booth and assisting them in making the marking.

Where did your passion for upholding the rights of people with disabilities come from?

Some of it is family. Questions had been asked when some family members were children about why they were a particular way. But does it matter? Can’t we just adapt around a child?

In my extended family, we also have someone who spent about 10 years in an assessment and treatment unit [a mental health hospital for people with learning disabilities or autism] and had experienced being in a seclusion room.

And then, throughout my career, I’ve spent time with people who really impacted me. Mark Neary and his son, Steven, were a big influence.

But when Mark talked to me about Steven, it was the small things I found more upsetting than some of the big abuses. There is a story about how important it was for Steven to have his socks and how the support workers disrupted what was a really important routine for him. The impact on Stephen was really powerful, it honestly made me cry.

I thought I could genuinely make a difference there, I could make sure that doesn’t happen to somebody else.

I’m also really lucky to call professor Sara Ryan a friend. Sara’s son, Connor Sparrowhawk, was 18 when he drowned under the care of the NHS.

Sara and Mark have managed to channel these extraordinary experiences of abuse and outcomes of willful neglect and somehow want to work positively with the social work profession to help us be better. I’m not sure I could do that.

As a social justice advocate, where do you think activism fits within social work?

An amazing university colleague, Hannah Morgan, organises a conference every two years with disabled people who are scholars in their field.

Talking to them, I realised they weren’t asking for us to do what I thought they would, which was about being supportive. What they were saying is, ‘Look, we want you to be more disruptive than that’.

They wanted allyship and allyship is quite an active word. It’s actively doing something different to disrupt the status quo.

[They wanted us to] push to disrupt, choose to work differently, to change how you think support is assessed or framed and what the purpose of that is. We are there to enable supported decision making.

We are not there to safeguard by wrapping people in forensic cotton wool, we are there to safeguard rights.”

Anybody can just fill out a form and the outcome from that is day care, respite, home care or residential care. It’s one of the easiest things to do in social work. You can fill those forms in within an hour. It’s not what social work is though.

Social work is the grey space in the middle, the bit that’s far less defined. That’s the space that social workers need to learn and occupy.

How can leaders support social workers trying to facilitate change?

I think every local authority needs a Mental Capacity Act lead working with the adults’ principal social worker to look at putting risk enablement frameworks around decisions.

So, when practitioners are making decisions that involve the least restrictive plans and there’s pressure on them, there is a framework with access to good quality adult social care legal services that can offer advice.

Practitioners need the best. They can’t do quality work if they can’t log on, find a desk or have to sit alongside colleagues listening to highly intimate personal conversations while they’re trying to ascertain information to scope out safeguarding concerns.

And there needs to be an honest view of workloads. Children’s caseloads are consistently said to be 15 to 16. In adult social work, my experience is that our caseloads are higher than that and growing.

There needs to be an open conversation about how much pressure can you genuinely put particular teams under.

What would you say are some misconceptions about working with people with learning disabilities?

The concern usually is, ‘How do you know what the person wants?’. But I’ve yet to meet a person who couldn’t in some way express to me their views and wishes.

For example, the social work manager at my service once worked with somebody who had a disability and had had a profound stroke. They didn’t speak in English and could only communicate through blinking.

All practical steps were taken to enable a bilingual speech and language professional to help communicate their right to choose where they ended their life. They wanted to be at home.

There is always a way to enable supported decision making if you are creative enough and you have access to enough resources.

Additionally, I think, learning disability is becoming a field where anybody who doesn’t meet a threshold for mental health services is supported.

The service that I manage is increasingly a service for adults who don’t have enduring mental health conditions. It’s a really exciting field to practise in because you’re working with people where the slightest reasonable adjustment can help.

It doesn’t have to be a lifetime of day care or home care or peers following them around all the time. Social work is the intervention – helping them form relationships, optimise their income, secure a place to live that feels safe, plan for a future.

What has been a defining moment in your career?

I have always been concerned about why so many people with learning disabilities and autism are trapped in hospital.

I’m really proud of the fact in Bradford we turned that around by lending our professional weight behind the views of the parents, who’ve argued and advocated strongly for those young people. In the last year, we haven’t had any long-term detentions under the Mental Health Act. I’m proud of that.

We’ve got nearly everybody home who we set out to get home. Each one of those is a really powerful story, but they’re not my story to tell.

There is also a young person whom children’s services were concerned about having a disability or neurodiverse condition.

She had been in the pupil referral unit as a result and was referred to us to help her a day service and other support with daily living. That’s not what she wanted. She wanted a job.

So, we found her a job in the council. She’s part of my team and goes out across the district to meet other people with learning disabilities. She has a questionnaire that she’s devised and she interviews those we support about the quality of our social work and whether their lives are better or whether there’s anything else that we need to do.

In the last year, she’s spoken to over 80 people with learning disabilities. Their answer is, no, there’s more we need to do to help people live better lives. To do that, we need to be better.

She is a real inspiration to me because things are just a little bit harder for her.

What lessons have you learned working alongside her?

However much I think I’ve made an adjustment to make things more accessible in terms of language, it’s not enough. There are more things I can do. It’s a reminder that I need to keep reading and learning.

She also teaches me daily that, if I explain something we’re doing in commissioning land and she doesn’t get it, it’s wrong.

The stuff commissioners are arranging which aim to make her life better – if she doesn’t get it, then it can’t be right, can it?

So that’s important to me that I don’t let my ideas dominate. It’s her life, so the ideas need to come from her about what being better means to her.

She also taught me that there can never be enough chocolate in the office!

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  ‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services

‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services  How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence

How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence  How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families

How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

I’m not an agency worker and never have been, but why cap the rates? Capping rates would just keep permanent social workers pay lower.

Agency rates generally just reflect the actual costs of employing experienced social workers anyway after you add how much it cost the council in employers national insurance and pension contributions. Sometimes it’s even less.