by Ray Jones

This article on social work in the 1980s is the second in a five-part series by Professor Ray Jones for Community Care’s 50th anniversary. Each part will look back at key events from the previous five decades – starting with the 1970s – that have shaped the social work sector today.

The 1970s saw the creation of a unified generic profession of social work and integrated social services within local authorities.

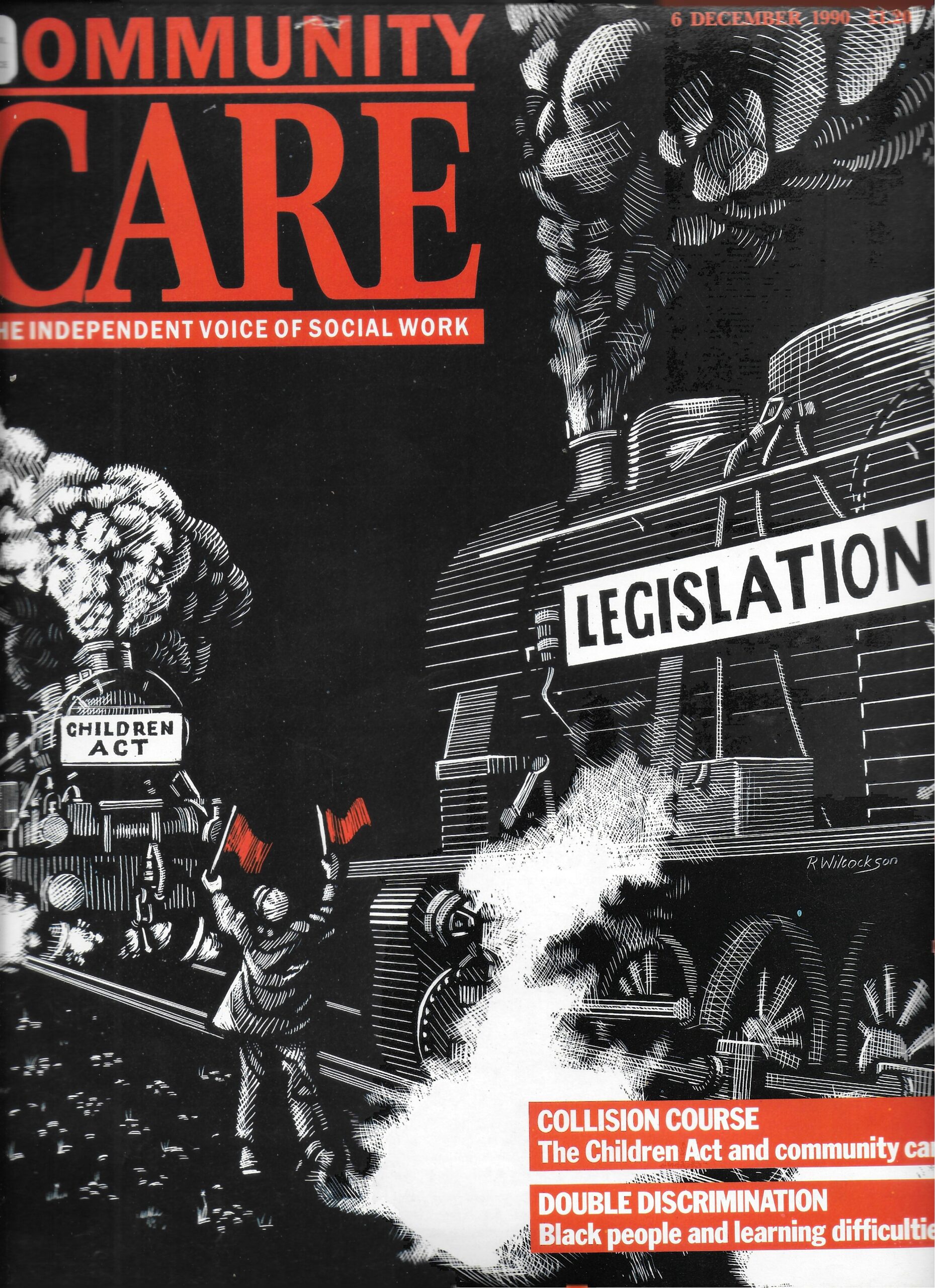

The 1980s was the start of a sea change with – as tracked by Community Care – the beginning of the separation between services for children and adults and increasing specialisation among practitioners.

It was two major reviews, conducted in the mid-1980s, that both led to the initial fragmentation of social services and cemented local government as having the key responsibility for them.

The first was undertaken by the Law Commission and looked at the legislation for children’s social care. It was seen as potentially consolidating the piecemeal legislative changes of the past 40 years and, as such, was largely undertaken under the political radar.

The Children Act 1989

The Law Commission review culminated in the Children Act 1989. This is still the legislative bedrock of both public and private family court proceedings and social work practice with children and families. It established the primacy of helping families with children in need and working in partnership with parents, and across agency boundaries, whilst also protecting and caring for children when necessary.

So how did an act which cemented local government’s role in leading and providing children’s social services emerge when public services were being castigated by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government? Two reflections.

So how did an act which cemented local government’s role in leading and providing children’s social services emerge when public services were being castigated by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government? Two reflections.

There was the significant impact of individuals who both shaped the legislation and stayed committed and active in delivering it. These included Rupert Hughes, who was the lead civil servant for children’s services throughout the 1980s.

A valuable lesson here is the importance of people in key positions who stick to the task of creating and delivering change. This contrasts with the churn and change of children’s ministers over recent years.

Another lesson is that sometimes it’s best to act under the radar and to push forward an agenda without too much attention. Children’s legislation would not have been a political priority for Thatcher – so it was best not to give it much of a profile when the consequence of doing so might have been opposition from number 10.

The NHS and Community Care Act 1990

The same was not so for the second major social services reform resulting from a 1980s review.

In 1987, Sir Roy Griffiths, deputy chairman of Sainsbury plc, was asked by Thatcher to undertake a review of community care for adults.

As with children’s services, previous decades had seen significant changes in policy and practice for people needing help and care. Prompted in part by scandals about abuse in long-stay hospitals, there had been a thrust to provide more services within communities, especially domiciliary care within people’s own homes.

Supported by research and also by a report from the Audit Commission, the life benefits of care within communities were increasingly recognised. Griffiths was tasked with making this more of a reality.

His 1988 report, Community Care: Agenda for Action, recommended transferring the money increasingly being spent on care homes from the social security budget to local authorities. This would allow them to strategically plan local services to provide help and care for younger and older disabled people within their communities.

Thatcher was not enamoured with the proposal to give more money and responsibility to local government.

More politically acceptable was Griffiths’ recommendation that local authorities should not be the providers of community care services but the commissioners, purchasing care from the growing private sector. Within this context, social workers were to be ‘care managers’, assessing need and, after discussion with service users, buying services from the care ‘market’.

What made Griffiths’ proposals politically attractive was not only that they promoted a privatised market, but that they presented a mechanism for capping and controlling the rights-based growth in social security expenditure on care.

Local authorities were tasked with containing community care costs within capped budgets. This was cemented in the National Health Service and Community Care Act 1990, and the resulting rationing persists to this day.

The legacy of the two acts

The two acts have taken social services and social work practice in two different directions. Social services departments created separate divisions for children’s and adults’ services whose social workers worked separately from each other.

The extensive policy and practice guidance the government issued in relation to each act also resulted in more specialisation, both between and within children’s and adults’ services. It was a major move away from the previously generic community social work towards separate and specialised services, which became less local and community-based.

The separation of children’s and adults’ services within social services departments was taken further with the 2004 Children Act, which led to the demise of those departments in England. That act required councils to bring children’s social care together with education in what are the children’s services departments that exist today, in separation from adult social services.

So it was the 1980s that planted the seeds for the separation and specialisation of the present day. It is its legacy that has social workers and leaders seeking to bridge the divides that have been created.

Ray Jones is the author of ‘A History of the Personal Social Services in England: Feast, Famine and the Future’ (Palgrave Macmillan 2020) and recently undertook the Independent Review of Northern Ireland’s Children’s Social Care Services.

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Some refreshing history, that is well told. I can not but wonder if these separations had done more harm than good in the overall journey of Social Work as a relatively new profession. Just wondered what the future design would be

Well done Jones

There’s most certainly a follow up article to be written here regarding the existing efforts to bridge the gap and work holistically and what can be further done in best practice to further support that. Considering the impact of the disconnection between adults and children’s services. They’re inextricably linked however a gulf exists. Particularly with mental health and with transitions for children and families. Food for thought. Interesting article.

the missing legislation from this account is the Mental Health Act 1983; crafted by the, then, national policy lead for MIND Larry Gostin heralded the real beginning of new Legalism ~ an import from the US; the lumping together and othering had to end and the splitting between providers and commissioners began in earnest ….

… the modernisation of local government followed in the noughties and drove the wedges home ~ for the first time VolOrgs and NGO’s had teeth and were prepared to bite; sick and tired of the same-old, same-old from statutory services planning arrogance and the profession hegemony of medicine …

…. Social Work was a week party to these discussions lacking the institutional clout and local representational confidence to hold sway never mind court …

… the Local Government Act 2001 alongside CCJ legislation placing on the face of the Acts the primacy of other departments, largely Crime and Disorder Partnerships, in the setting up of a new and energetic 3rd Sector…

…. the adage from the Chronically Sick and Disabled Persons Act 1968 ‘Adding Life to Years and Years to Life” the mantra of the Blairites and most notably across the personalisation and world class commissioning agenda….

… education, education, education was the rallying cry as the, then, SoS of State David Blunkett alongside the SofS for Health Frank Ducan wheeled out an unprecedented plethora of social and public policy reform …

… it was no longer required that the Council CEO and/or Director of Social Services had been a Children’s Services Social Worker….

… VolOrgs soaked up those managers caught in the churn and contracting let on an almost friends and family basis ~ that is until questions of fairness were raised and to which public procurement became the next stage of a self-created market ~ the beauty contests had started and low and behold those who dare shout out about it …

… performance management became the scape goat for everyone and everything….

… for sure it was blindly and haphazardly implemented but only when it suited those who were the suited and booted …

… Government has never been so close to this new unelected Officer class travelling first class and often unannounced to walk-the-talk of the new masters of the Universe …

… and it was encouraged and celebrated, including BASW who held interests with the new elite…

… we have arrived at the MacAlister Review because that’s what was really planned for all along …

… Prof Jones knows this too so let’s get real for once…

Have you asked David Hinchcliffe, the former social worker and MP, for an interview?

I have always been impressed by his candour in difficult times, firstly as my Dad’s psw when I was as a child, secondly, during the hospital closure programme at the height of the Community Care reforms, and thirdly as a senior child protection social worker investigating any known information about the abuse of UK Irish by the Christian Brothers.

His time as Chair of the HofC Health Committee like that of Kevan Barron MP, and Chair of the Inquiry into Commissioning 2010, would shed much more light on the actual consensus of the 1990’s and throughout until 2010.

The syndication of financial abuses between Officers and NGO’s is a better story to tell, no?

Taken Without the Consent of the Owners (TWOC) would make for an apt feature article; not least because young offenders, my niece’s included, were used as guinea-pigs for the now taken-for-granted advances made in voice recognition and super language modelling of big tech; meanwhile, their lives were obliterated to, and literally so, extinction. The issues faced by the underclass are now about surviviance and the apocalyptic collapse of the social contract.

Accurate chronicles of history don’t always breath life into the events described. I am one of many who cautioned against separation of services and enthusiasm for embracing commissioning over locally provided, politically accountable local authority provision. For which we were vilified and dismissed as anti- progress stick in the muds but have been proved right. Users of services are not better served now by fragmentation, silo kingdoms, budget determined commissioning, proliferation of unaccountable and at times abusive providers. We gave up local democracy and meaningful community engagement not just because we were forced to by political forces but also because of the self interest of those who bureaucratised our work and curtailed our autonomy for their own pet project to ‘professionalise’ social work. So here we are, sterile faux professionalism at the expense of dynamic social work practice. Millions of words and this still is indisputable reality. I could be wrong of course given we have titans running SWE and BASW, one which apparently regulates social work to improve its practice and empower the public and the other a ‘professional membership association’ that claims to champion social work and social workers. Virtue is in the eye of the beholder they say though. So for some of us SWE is just a fee pursuing authoritarian enterprise more interested in sanctioning social workers and structurally incapable of understanding experiences of social workers and BASW a vessel for fad driven cosy pals chats influencing nobody of any significance and making not a jot of difference to what social workers actually do.

Your analysis of SWU is way off the track. There’s no evidence of authoritarianism and they have some good positions on some issues that sets them apart from BASW. The issue for SWU is it’s inability to represent it’s members (who are better off in UNISON or UNITE) on pay and conditions. A trade union is hamstrung if it has no recognition rights for collective bargaining purposes. SWU is not affiliated to the TUC partly because it does not distinguish itself enough from it’s partner BASW. SWUs recent excursion into ‘reflective’ practice for example was an odd terrain to tread as a trade union when you’d think that would be better left to BASW.

Having lived through the split I believe we lost our way. In so doing we laid the foundations for a much more instrumental practice creating new silos whose fracture lines are now chasms and where adult and children’s workers working together is a form of interprofessional/multi professional practice with so much experiential knowledge now lost to the vaults of time!

But the lumping didn’t work either ~ the mdt approach spreads the liabilities for decision-making while limiting ratherthan information management; it’s dangerous.

The extent, nature and degrees of State Liabilities for vulnerable populations, the increasingly populist definitions of what constitutes vulnerabilities, and the crazy metrics of measures for doing so is based on what?

What knowledge base? What value base ? What ethic ?

Q: Do We Care ?