by Ray Jones

This article on social work in the 1990s is the third in a five-part series by Professor Ray Jones for Community Care’s 50th anniversary. Each part will look back at key events from the previous five decades that have shaped the social work sector today. His previous pieces covered the legacy of the Maria Colwell inquiry in 1974 and the birth of the divide between adults’ and children’s services in the 1980s.

Practice often follows changes in legislation and policy, but there are also examples where developments in practice prompt new legislation.

This was so in the early 1960s, when social work practice switched its focus to supporting families to care for their children, away from the Children Act 1948’s emphasis on foster and residential care away from families.

That change led to the Children and Young Persons Act 1963, followed later by the Children Act 1989.

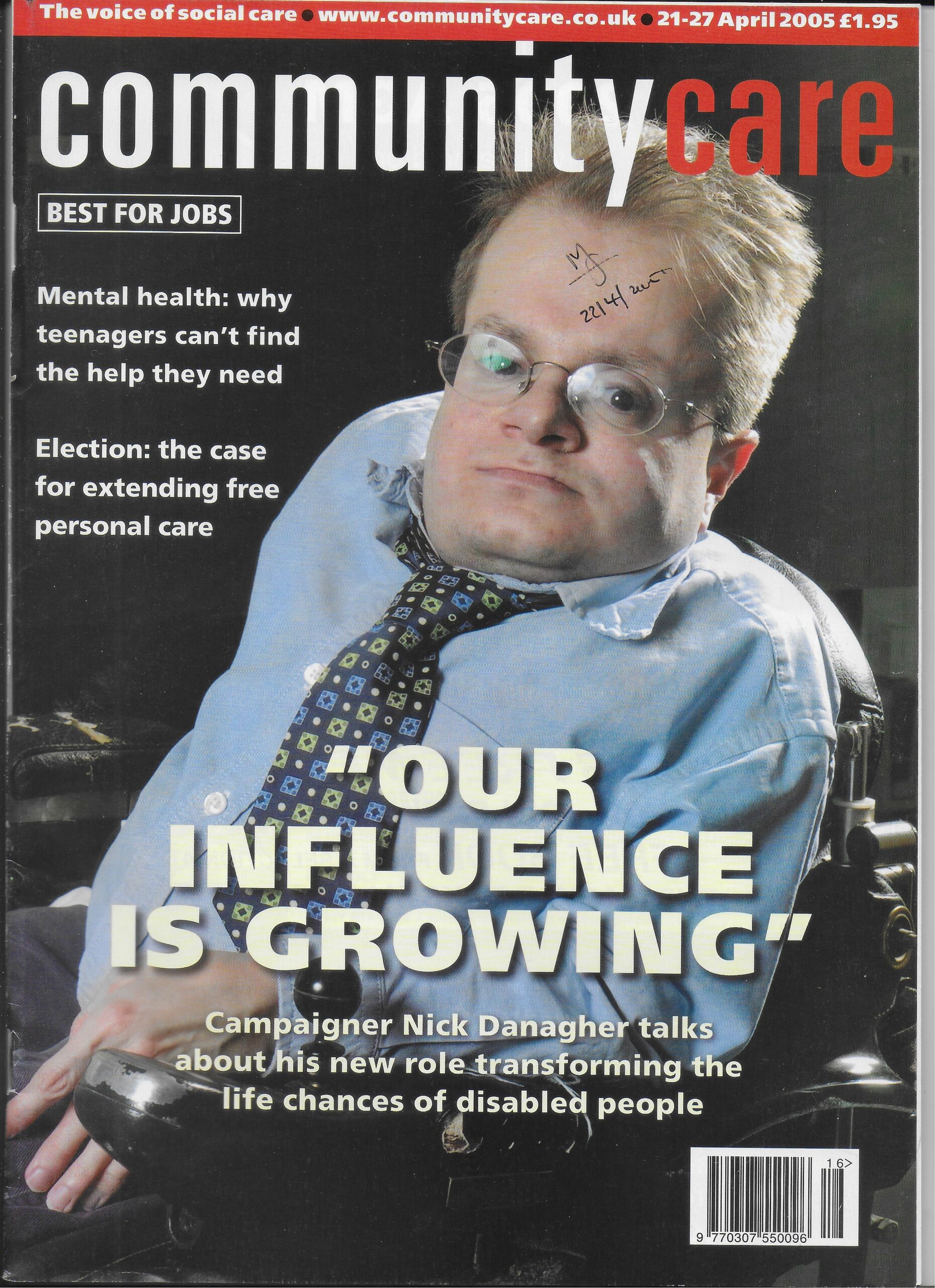

It was changes in practice that also led to the 1996 legislation that introduced direct payments for disabled people. The practice changes were pushed by disabled people and the impact of the disability movement was tracked over the decades by Community Care.

The rise of the disability movement

Photo by Ray Jones

It was disabled people who shaped the social model of disability, demanded better rights and challenged the patronising and paternalistic practice they experienced. They took social workers and other professionals on a journey of understanding that our job was not to do ‘to’ or ‘for’ disabled people but to work in partnership with them and, as allies, support them in deciding by themselves how they wanted to lead their lives.

It was a movement that necessitated civil disobedience. This became possible with the support of various organisations such as the Disabled Action Network, leaders who helped set agendas and activists including John Evans, Mike Oliver, Jane Campbell, Jenny Morris, and Nick Danagher.

There were also disabled activists, such as Clare Evans in Wiltshire, who canvassed for change locally in public and private services, such as housing, transport, shops, and leisure facilities, campaigning for improved access but also changes in attitudes. They also set up local ‘user networks’ and centres for independent living, led by disabled people themselves.

The move to (in)direct cash payments

Photo by Ray Jones

One of their demands was that disabled people should have a choice about, and control of, the type of assistance they might need. This may not sound so radical now, but it was a step change in the 1990s.

It led to several local authorities – including Kingston, Hampshire and Wiltshire – taking action to introduce early versions of what were to become direct (cash) payments. This allowed disabled people to determine the use of the money that, until then, had been allocated by councils for pre-determined services.

Share your story

Photo: daliu/fotolia

Would you like to write about a day in your life as a social worker? Do you have any stories, reflections or experiences from working in social work that you’d like to share or write about?

If so, email our community journalist, Anastasia Koutsounia, at anastasia.koutsounia@markallengroup.com

For example, it enabled ‘willing and able’ disabled people to recruit and employ personal assistants, participate in local clubs or attend sporting events.

But this was ahead of any legislation to allow social services departments to transfer cash to disabled people. So creative and intricate arrangements had to be made to transfer the money to a third party organisation, such as a local charity, which would then pass it on to the person with care and support needs.

The Community Care (Direct Payments) Act 1996

It was the success of these indirect payment schemes, and the continued campaigning by disability activists, now with the support of some councils and social services leaders, that led to the Community Care (Direct Payments) Act 1996.

It gave councils the discretionary power, though not a duty, to transfer money directly to disabled people.

It was a step change in practice that highlighted the potential power of collective action by disabled people.

The people left on the sidelines

Initially, older people were excluded by the legislation from receiving direct payments. There was also a reluctance in some areas to include people using mental health services or people with a learning disability within direct payment schemes.

The argument for this was that. although they might have been ‘willing’ to receive and use direct payments, there was less confidence about whether they were ’able’ to use them appropriately.

However, experience, along with support from centres for independent living, showed that direct payments could and should be available more widely.

The Carers and Disabled Children Act 2000 gave councils the power to make direct payments to 16 and 17-year-olds and carers. A year later, the Health and Social Care Act 2001 made it a duty for local authority social services to make direct payments available for all disabled people with social care needs, including those with mental health difficulties or a learning disability, and people aged over 65.

The downturn of the 2010s

What has happened since?

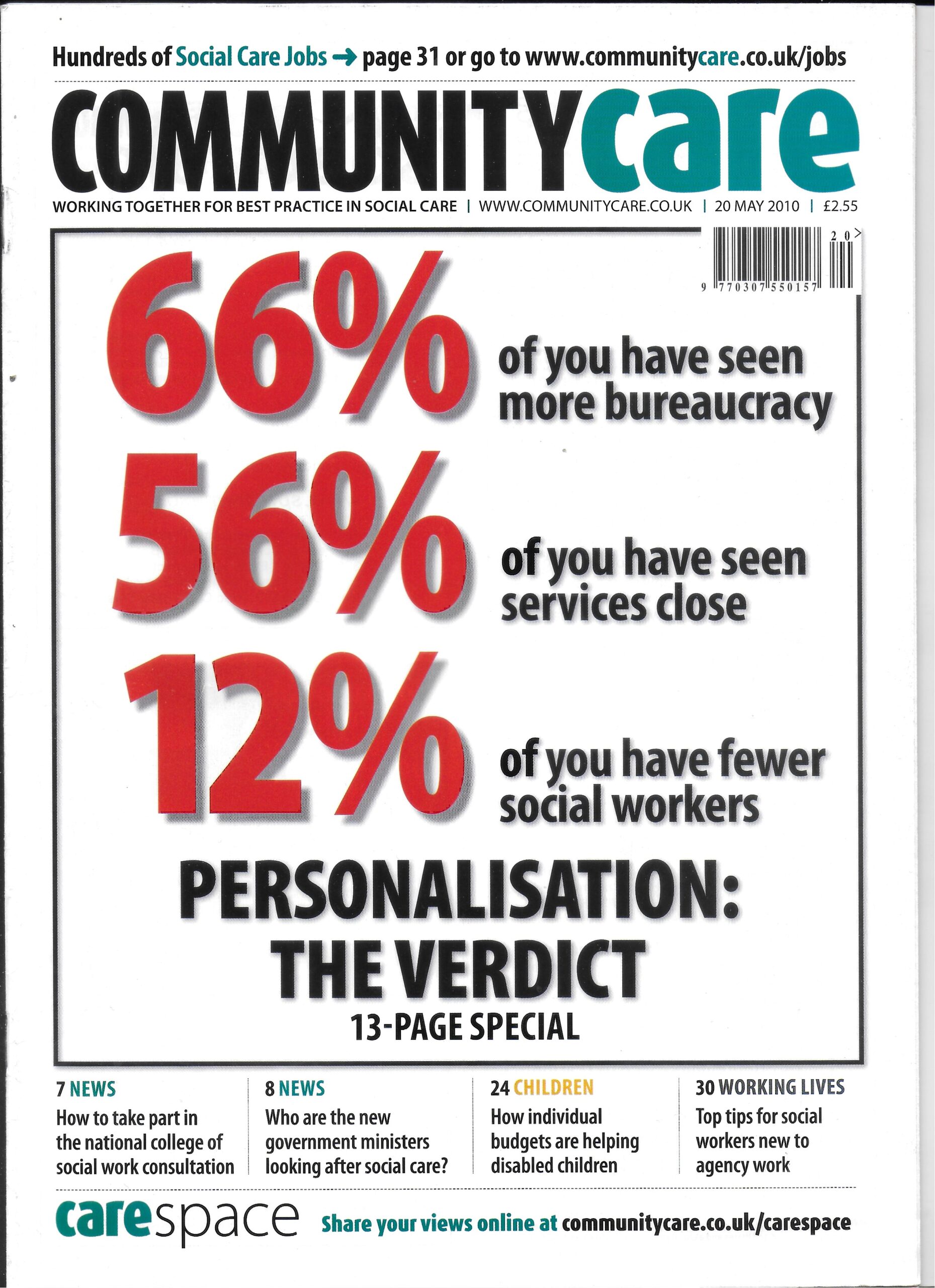

Much of the promise of disabled people’s right to choice and control through direct payments has been stymied by increasing proceduralisation and a growing emphasis on rationing and curtailing local authority expenditure.

Photo by Ray Jones

In 2010, Community Care undertook a survey with UNISON, which found that direct payments were leading to increasing bureaucracy, both for those working within local authority social services and also for disabled people.

Even before the advent of 14 years of politically-chosen austerity targeting public services and welfare benefits, cuts in services and funding were undermining the opportunities and life experiences of disabled people.

The need for ‘a step back to the past’

So what’s the verdict in 2024?

There has been movement away from the paternalistic provision of services to more partnership and engagement with disabled people.

The move to personal budgets, where an amount of funding is available for discussion about its use, has also been positive.

This has offered more flexibility than the previous system, where disabled people had to either accept a cash transfer and bear the burden of arranging and managing their assistance on their own, or leave control over their support with their council.

But an unintended consequence of direct payments and personal budgets is that disabled people are drawn into the requirement and responsibility to ration the assistance they need.

This has worsened over the years due to the stream of government funding cuts. And unlike the closure of a day centre or residential care home, cuts to personal budgets are largely unseen by the public at large.

The question now is whether there can be a political pivot back to the promise of the changes of the 1990s and away from politically-nasty and niggling narratives that demoralise and demonise disabled people.

Ray Jones is the author of ‘A History of the Personal Social Services in England: Feast, Famine and the Future’ (Palgrave Macmillan 2020) and recently undertook the Independent Review of Northern Ireland’s Children’s Social Care Services.

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Oxfordshire County Council

Oxfordshire County Council  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Webinar: building a practice framework with the influence of practitioner voice

Webinar: building a practice framework with the influence of practitioner voice  ‘They don’t have to retell their story’: building long-lasting relationships with children and young people

‘They don’t have to retell their story’: building long-lasting relationships with children and young people  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  How managers are inspiring social workers to progress in their careers

How managers are inspiring social workers to progress in their careers  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

The article talks about a move away from paternalistic systems that controlled disabled people and left them voiceless.

How ironic that Community Care should replicate this paternalism and silencing of disabled people by asking a non disabled academic and former Director of Social Services to tell the story of the Disabled People’s movement.

To compound this error the author forgot all about the first system of Direct Payments, the Independent Living Fund,.which was.set by the then Benefits Agency (?) in 1988 to provide cash payments directly to disabled people to fund their own support. In this initial phase payments were independent of local authorities.

It was.reformed in 1993, to coincide with the introduction of the NHS and Community Care Act, to top up support funded by a local authority.

Wikipedia can fill in the rest …..