This article presents a few key considerations from Community Care Inform Children’s guide on understanding ‘disguised compliance’ and how to apply a relationship-based approach to removing barriers to parental engagement. Inform Children subscribers can access the full guide here.

This guide was written by Jadwiga Leigh, founder of New Beginnings, a foundation working to support and keep families together, and a part-time senior lecturer in social work.

‘Disguised compliance’

“Disguised compliance involves parents and carers appearing to co-operate with professionals in order to allay concerns and stop professional engagement (Reder et al, 1993). Published case reviews highlight the importance of practitioners being able to recognise disguised compliance, establishing the facts and gathering evidence about what is actually happening in a child’s life.” (NSPCC Disguised Compliance Briefing, Oct 2019)

The first time the term ‘disguised compliance’ appeared in social work literature was in the book Beyond Blame (Reder et al, 1993). The authors coined the term ‘disguised compliance’ to succinctly describe how they found some parents responded to professional involvement in the inquiries they read.

A common feature in case reviews was that professionals missed ‘disguised compliance’ by parents and needed to be more alert to the signs and be more questioning, displaying more ‘professional curiosity’.

They told professionals that the signs of disguised compliance to look out for in parents are:

- a sudden increase in school attendance;

- attending a run of appointments;

- engaging with professionals such as health workers for a limited period of time;

- cleaning the house before receiving a visit from a professional.

Practitioners now had a set of criteria that they could use to identify this kind of behaviour when it occurred. As a result, the term ‘disguised compliance’ easily integrated itself into social work practice because it offered a two-word phrase that captured the complexity of families in the welfare system. The term started to appear regularly in serious case reviews, government reports, academic articles, factsheets relating to child abuse and social work blogs.

Rethinking the term ‘disguised compliance’

However, over time, the concept has come to be questioned, including because it may divert social workers from considering why parents may conceal things from them and how they can work more effectively with these parents.

If we are to meaningfully help parents whose behaviour harms their children, we need to first consider the functioning and needs of the parents.

The way our current welfare system works is almost entirely organised around the needs of children, hence why it is often referred to as safeguarding or child protection.

However, what this approach misses is that all parents were once children themselves. In many situations, they have had involvement with social services as children. Pat Critttenden, author of Raising Parents (2008), states that from the extensive research she has conducted internationally over the years, three common themes among parents whose children are in the child protection system have emerged:

- Even when parents harm their children, they almost never intended to do so.

- Harmful parental behaviour has roots in what parents learned in their own childhoods – that is, parents were also threatened or harmed as children.

- Parents seek to raise their children better than they were raised

Practice point

When working with families, and considering compliance or non-compliance, it’s worth thinking about why parents are engaging with some professionals and not with others. It’s also worth thinking about how their past experiences with social care professionals have influenced the way they interact with them today.

If a parent has suffered abuse in their childhood, they will have developed strategies that kept them safe as a child, such as avoidance or withdrawal from the caregiver, strategies that the parent uses in the unconscious belief they will to continue to keep them safe in adulthood but, in reality, are now having the opposite effect.

For example, by hiding from a social worker, a parent is likely hoping to deter them or keep their children safe at home – but the act of hiding is going to work against them and perhaps lead to greater intervention. Working with intergenerational trauma is not simple, but considering how parents we work with have learned to make meaning from the world and organise their behaviour can make a significant difference to child protection work (Crittenden, 2008).

Applying a relationship-based approach

The professional encounter between parent and social work practitioner should be used as an opportunity to work both in and with the relationship to promote change (Turney, 2012).

Relationship‐based practice recognises that people want to be understood and be treated as an individual in their own right rather than parents simply being seen as ‘a means to an end’ in terms of protecting their children from harm (Turney, 2012: 150).

If collaboration from parents is not actively sought by professionals, then a lack of parental investment is a most likely outcome. When this happens, more often than not, the parent is seen as ‘the problem’ rather than the solution. And if parents feel they are being stereotyped as ‘bad parents’, it can lead to relationships between them and professionals deteriorating even further (Webb, 2006).

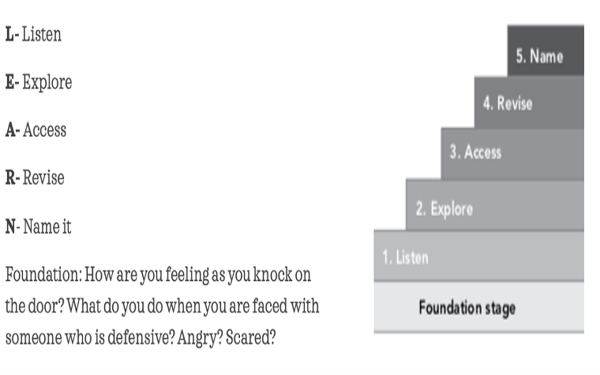

The LEARN model

One practical tool that practitioners can use to improve their communication with families is the LEARN model. It was specifically designed by Baim and Morrison (2011) to respond to three key questions from practitioners they had worked with over the years:

- How can attachment theory help us to form a clearer picture of the difficulties faced by the people we are assessing and trying to help?

- How can we use this clearer picture to help people better understand themselves, and to help them find their way to more satisfying relationships at home, at work and in the community?

- How can we use the same concepts within supervision to help support and develop practitioners?

Photo: Baim and Morrison (2011)

A key feature of the foundation stage is for practitioners to acknowledge how they feel (see above diagram) and to be aware of how they communicate with the potential ‘involuntary client’. Baim and Morrison highlight the importance of the practitioner being respectful, collaborative and containing.

If you have a Community Care Inform Children licence, log on to access the full guide and learn more about applying ‘disguised compliance’ and how to apply the LEARN model.

What to read next

- Increasing parental motivation and aspiration

- Attachment-based parenting and trauma

- How to use professional curiosity to understand social and emotional responses

References

Baim, C, Morrison, T (2011)

Attachment-based Practice with Adults: Understanding strategies and promoting positive change: A new practice model and interactive resource for assessment, intervention and supervision

Crittenden, P (2008)

Raising Parents : Attachment, Representation and Treatment

NSPCC (2019)

Learning from case reviews briefings: Disguised compliance

Reder P, Duncan S, Gray M (1993)

Beyond Blame: Child Abuse Tragedies Revisited

Turney D (2012)

‘A relationship-based approach to engaging involuntary clients: The contribution of recognition theory’

Webb, S, A (2006)

Social Work in A Risk Society: Social and Political Perspectives

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Oxfordshire County Council

Oxfordshire County Council  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Embedding learning in social work teams through a multi-agency approach

Embedding learning in social work teams through a multi-agency approach  The family safeguarding approach: 5 years on

The family safeguarding approach: 5 years on  Harnessing social work values to shape your career pathway

Harnessing social work values to shape your career pathway  Webinar: building a practice framework with the influence of practitioner voice

Webinar: building a practice framework with the influence of practitioner voice  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters  Free CPD on Parkinson’s for health and social care staff

Free CPD on Parkinson’s for health and social care staff

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

A huge problem with disguised compliance as a concept is that it ignores that practice often sends parents the message that compliance, rather than change, is what is expected of them. If you frame a Child in Need or Child Protection plan as a series of tasks to be completed without tethering them to second order change, when you use threats rather than a desire to do better by their children as the motivation to do those tasks, don’t be surprised when parents do those tasks while continuing to parent in fundamentally the same way.

trauma bonds are systemically replicated and recursive throughout, no?

say more, dk….

dk im prompted by your use of the words ‘second order change’ and wondered if you are referencing or using the work of Maturama and Verela on autopoissis, cybernetics and feedback loops, and especially Verela’s early working on systemic family therapy AND (or) say, psychosocial-neuroscience of Internal Family Systems and Nigel Parton’s work on Deep and Surface Structures in Child Protection ie mimetic desire and the pkease/appease/fight/freeze of trauma bonds ….

… And, I am trying to weigh (see John Broome on Weighing Lives) whether the macro or maybe meta narratives are economically shaped by, what/which practice and theory modelling ie the US, the Danes, India or Australia (who have adopted the Chilean model) as part of the processes for reaching trade agreements ~ the MacAlister Review is heavily loaded towards the US….

… the omission of Black Perspectives is, as said before in CC is in plain sight ….

… the continuing white euro centricity is obviously obvious, no? …

… thoughts ….

And, while my attention is still with this thread one of the contributions from Messages from Research (MfR) alongside Partons work on Deep and Surface Structures in Child Protection was Private Lives and Public Risks by Elaine Farmer and Morag Owen which includes an empirical focus on how meeting the needs of parents was/wasn’t satisfied; pressure of time/volume of work the stand out factor …

This is very interesting and thoughtful.

dk your comments are so true.

Disguised compliance is not a tick box, social workers should have space to analyse,observe behavior,further explore and evidence parents are not just complying with a tick box process.

Every process, values principles and practice are interlinked.Pratice involves being aware of all the required social work practice and procedures if the profession is to be viewed as a necessary and relevant service for all. Does it not?

Is anti-discrimary practice not about self-awareness,questioning one’s practice based on evidence and for the right reasons in respect of the child, questioning one’s beliefs,decision making.

“Have I fairly considered the child’s,adults ,Individual needs”

Is this not a relevant and non judgemental process to do in such a profession? My opinion is it is however it is who,how such discussions take place.In my view again is considering how this will be achieved? So many questions need to be considered!! If it is to be explored in practice.

In my opinion society is now about doing more in less time. I do not believe this should/ can be the mind set in child protection.In my opinion all aspects of the values and principles are relevant,change is relevant,self- awareness,uncomfortable conversations in a safe environment is necessary especially in this profession to ensure practice and decision making are fair for all.

These are my experiences,some may not agree,however we work with vulnerable children,they are dependent on all who are involved in their lifes making decisions based on the right reasons by all. Are they not?

I can expand further to evidence my thinking but will not do so.

the proposed devolution of adoption and fostering funding will be subject to what/which allocation mechanism? are the Regional Purchasing Organisations (and the associative procurement) continuing to lead practice? is the requirements of secondary legislation casting an overarching shadow shaped by trade-agreements? what are the surface and deep assumptions and values in play? can ‘we’ prescribe and specify such services? is it OK to treat children as lots to be competitively against ?

thoughts …

Children are human beings they to are our future !!

When a child is placed for Adoption it is a serious and final decision with the intentions they will achieve their best potential.Support should not stop or reduce once children and or young people have been Adopted.Social work intervention is needed at every stage.Therapeutic intervention is needed,lifestory work from birth to their current position is needed, forming connections with someone they trust to enable support through their life’s journey is important has it is for any other child/young person.

If support and appropriate funding is reduced can we be sure children will be receiving the right safeguards and support?

Will social workers have the time and support to connect with the child and Adoptive parents.Not all Adoptive placements are positive experiences for the child,social workers must have meaningful connections with the child to ensure postive emotional development.Can we say this will happen for the child with reduced funding and the current mind set ?

Without informative supervision which includes time to offer safe reflective practice,being aware of disguised compliance,attachment theory,safeguarding in any situations to name a few.

What will be the safeguards in place from all levels?

Social work is complex it involves Metacognition-self reflection deliberate and disciplined critical assessments of one’s own thinking,questioning why we think as we do.Ennis (2011)”Critical thinking is reasonable,reflective thinking that is founded on deciding what to belive or do”(p.12).I ask can social workers really provide for vulnerable children and young people with reduced funding and services not being appropriately funded?

Is the expectation more for less,tick boxes with little or no real value for the children we are here to safeguard at all levels.

Social workers opportunities to but into practice the skills and knowledge we acquired with tick boxes appears to be the norm.

Not helpful for the child and or social workers who want to see children thrive with their intervention.

These are my opinions based on working with children.Children are adopted for various reasons,they experienced trauma in their life’s the liklyhood is they may continue to do so after adoption (this may not be the case for all).Is this not the time they need high levels of funding and support inorder that they can achieve their best potential.

Everything has a knock on effect at all levels!!

@meta-cognition ~ the feature article pushes attachment anxiety but what responsibility does one have for baulking against the latent germanic hermetic hinted at here? …

… I mean how does one act against such a deeply ingrained world view …

…. the Climbe Inquiry required a revision of, what? Witchcraft, right? ….

… Without any reference to the sewn-in background noise of the white protestant siren call of ‘out of sight out of mind’ ‘or the clip around the ear won’t do any harm’ …

… the term meta is too being pushed by evaluation methodologists in a bid to get above it all …

… thing is that by attaching more value on the espoused and often conceptual knowledge acquisition than the actual theory in use ie behaviours management failure becomes systemic, no? …

…. and, if it’s all connect (btw I agree) what purpose does this serve, and crucially for who? …

… I provoke; what has attachment theory got to do with the second order cybernetics dk talks of; does Critical Systems Heuristics have anything to offer (see Werner Ulrich) ….

…. more thoughts 🤔, maybe ha ha …

If we look at second order principles this could be the same as critical thinking.It requires looking beyond the surface/immediate affects and considering the broader impact/longterm consequences how this affects the child parent relationship and social work assessment.

This may in turn, require drawing on attachment theory and various other practice and theoretical approaches to ensure we have covered all aspects in the child/parent relationship to make informed decisions and identify compliance behaviours all are interlinked is it not?

I am open to other views.

von Forrester, Margaret Mead, Nora Bateson, right ?

And, hot off the press ‘The Humiliated Father: A conversation with Daniel Tutt’ which is part of the Negative Psychoanalysis programme run by Julie Reshe; Tutt takes a through the life course perspective on the Oedipus Complex dissolving, perhaps, the theory/practice tension between the Deleuzians and Freudians forcing to the foreground latentency of subjective beliefs ….

… for more on beliefs see William James and his James-Lange Theory of Emotion and our ability for deletions, distortions, and generalisations …

… anyways >>> ….