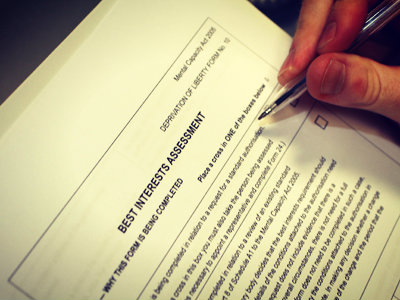

The Law Commission wants its proposed replacement for the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (Dols) to be simpler for professionals to use without compromising human rights protections.

Speaking at the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (Adass) spring seminar last week, the commission’s public law head, Nicholas Paines QC, said it would launch a consultation in July on a proposed new system governing deprivation of liberty.

This would cover care homes and hospitals as well as other settings not covered by the Dols, such as supported living.

The government asked the commission to draw up proposals for reform last year after the landmark ‘Cheshire West’ Supreme Court ruling (see below) triggered a surge in deprivation of liberty cases, and a highly-critical House of Lords committee report described the Dols as “not fit for purpose”

‘Less cumbersome’ system needed

Paines, who was expressing his own views as the commission’s final plans for consultation are yet to be finalised, said a “less cumbersome” scheme was needed than Dols. He pointed to the fact that the complexity of the current situation had required the Law Society to produce almost 140 pages of guidance to help staff identify what constitutes a deprivation of liberty in care.

“You can’t expect a hard-pressed social worker to apply 140 pages of guidance before he or she decides whether what is being proposed is a deprivation of liberty or not,” he said. “There will have to be a simpler, easier to apply set of criteria for triggering our scheme.”

The commission was also considering whether the new scheme should introduce more safeguards to a person’s liberty earlier in the care planning process. This would contrast with the current system where the Dols decision-maker is asked to authorise care decisions that have already been made by a care provider or social worker, Paines said.

“The Dols scheme was really conceived to make legitimate a decision that had already been taken. I’m not criticising it as a rubber stamp, not all Dols applications are granted – around a third are not,” he said.

“But it’s very much the case that the Dols decision-maker is faced with a decision that has been taken by a social worker and the Dols decision-maker is asked to authorise it. We think it might be better to introduce more safeguards to liberty before the intrusive decision about the person’s care or treatment is taken at all.”

The right balance

The commission wanted to strike the right balance by developing a system that was grounded in the Mental Capacity Act and offered effective safeguards but was more straightforward than the Dols, Paines said. The commission was also thinking about the role of advocacy in the new scheme, particularly in light of the Care Act, to ensure there was “someone in the room waving the flag for liberty” in the new process, he added.

The consultation on the Law Commission’s proposals will last four months. Draft legislation will not be published until 2017.

About the ‘Cheshire West’ ruling

The Supreme Court’s judgement in the linked cases of P v Cheshire West and Chester Council and P&Q v Surrey County Council in effect lowered the threshold for what constitutes a deprivation of liberty in care.

The court’s “acid test” said that a person who lacked capacity to consent to their care arrangements was deprived of their liberty, under Article 5 of the European Convention of Human Rights, if:-

- they were under continuous supervision and control;

- they were not free to leave, and;

- their care arrangements were the responsibility of the state.

The ruling rendered irrelevant factors that had been allowed for in the past, such as whether the person objected to their care arrangements.The Supreme Court also made clear that such a deprivation of liberty would apply in a domestic setting, as well as in health or social care placements.

The judgement was welcomed for extending key human rights safeguards to a broader group of vulnerable people. But it meant that, overnight, many people in care homes, hospitals and supported living arrangements suddenly met the threshold to have their care arrangements assessed or reassessed to see if they were deprived of their liberty and, if so, whether or not this was in their best interests.

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

If a person has made their wishes for care provision in a power of attorney, then hopefully their liberty will be respected accordingly?