One in five children’s social work posts lay vacant in English councils this summer in the wake of practitioners reporting rising stress and workloads and reduced job satisfaction and support from employers.

Those were among the findings of research released this week from the Department for Education and Association of Directors of Children’s Services (ADCS), illustrating the scale of the workforce pressures engulfing local authorities.

The studies followed warnings from Ofsted in its annual report this week that social worker shortages were making an already challenging job “unsustainable” for some practitioners and driving others into agency work.

Sharp rise in vacancy rate

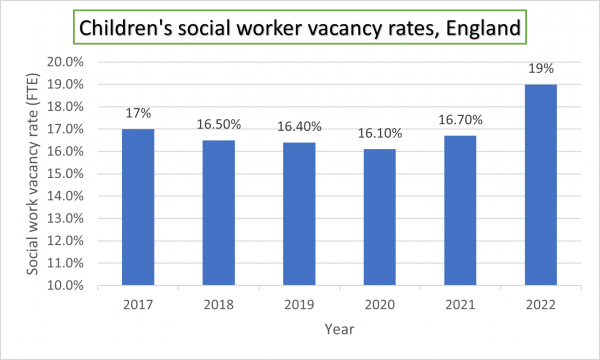

In the latest full report from its safeguarding pressures research series, the ADCS found that the social worker vacancy rate had risen from 14.6% to 19% in the year to June 2022, based on data from 108 of the 152 councils.

The figure marks a significant jump on the 16.7% reported by authorities in September 2021 for the DfE’s latest official children’s social work workforce data collection.

Sources: Children’s social work workforce collection (Department for Education), 2017-21, and Safeguarding Pressures Research Phase 8 (ADCS), 2022

Directors also reported an increase, from 15.6% to 16.7%, in the proportion of their workforce who were agency staff in the year to June 2022, which was also above the DfE figure reported for September 2021 (15.5%).

Directors not confident about social work capacity

In the light of the vacancies, 44% of respondents to the ADCS research stated that there were never or rarely enough social workers in the right places to effectively support children.

Meanwhile, a DfE report published this week found that 70% of directors, surveyed in January to March this year, were not confident they would have enough permanent children and families social workers over the subsequent 12 months to meet their needs.

The finding, based on data from 50 directors, is a sharp increase from the 40% recorded in October to December 2019, for the previous wave of the children’s services omnibus, the DfE’s regular snapshot of leaders’ perceptions of the state of the sector.

Leaders are also finding it more difficult to recruit to all roles:

- 94% said they were finding it difficult to recruit experienced social workers in early 2022, up from 87% in late 2019.

- 58% said it was difficult to till team leader posts, up from 49%.

- 40% found it difficult to recruit senior managers, up from 34%.

- 14% found it difficult to find newly qualified social workers, up from 4%.

At the same time, separate DfE research with children’s social workers has identified that practitioners were experiencing rising stress and workloads but feeling less supported and valued by employers towards the end of last year.

Increased stress and workloads and reduced job satisfaction

- 62% (surveyed September to December 2021) felt stressed by their job, up from 60% at wave 3 (surveyed September to December 2020) and 51% at wave one (surveyed November 2018 to March 2019).

- 61% said they were asked to fulfil too many roles, up from 55% at wave 3 and 47% at wave 1.

- 59% said their overall workload was too high, up from 58% at wave 3 and 51% at wave 1.

- 61% felt valued by their employer, down from 56% at wave 3.

- 68% agreed they had the right tools for their job, down from 76% at wave 3.

- 68% found their job satisfying, down from 72% at wave 3.

Respondents cited Covid-19 as among the factors driving these trends, with 76% saying it had increased the complexity of cases, up from 68% at wave 3, 73% saying it had increased workloads (up from 69%) and 73% reporting it had led to a rise in work-related stress (the same as in wave 3).

Among those who felt stressed, 62% cited paperwork as a driver, up from 55% at wave 3, 45% having too many cases (40% at wave 3) and 44% a lack of resources to support families (35% at wave 3).

In relation to the drivers of reduced job satisfaction, there had been a drop since wave 1, from 83% to 73%, in the proportion who were satisfied with the sense of achievement they got from work, while the percentage satisfied with the opportunity to develop their skills had fallen from 72% to 66% over this time.

Workforce attrition

There had been an increase, since wave 3, in the proportion of who were still in local authority children’s social work, including in an agency role, from 88% to 83%. Researchers said it was expected that people would move out of the sector over time.

The proportion working in social work – but not for a local authority – had doubled from 4% to 8% since wave 3, while there had been an increase, from 2% to 3%, in those employed outside of the profession, and a rise, from 3% to 5%, in those who had retired or were doing something else.

Despite the challenges, 81% of those still in local authority children’s practice, including agency staff, said they expected to be so 12 months on from the survey – ie around now. Three per cent anticipated a move into the private or voluntary sectors, 3% into another area of social work, 2% into retirement and 6% did not know their plans or preferred not to say.

Care review call for national pay scales

The reports with the Department for Education due to provide its response to the Independent Review of Children’s Social Care early in the new year.

The review’s key measures to improve social work recruitment and retention were the introduction of national pay scales tied to progression through and beyond a five-year early career framework, along with tighter regulation of agency work.

“These pay scales are expected to address the discrepancies in how social workers are paid through the local government pay scales, reduce competition between local authorities, and incentivise social workers to remain in post so children and families do not have multiple social workers,” said the review, led by former Frontline chief executive Josh MacAlister.

In its initial response to the review’s final report, in May this year, the DfE indicated its support for the early career framework, while it is also expected to announce measures to curb agency social worker use in its response. However, it has not commented on the proposal for national pay scales.

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Not exactly a surprise from those of us on the front line!

And, yet, nothing will change.

It is physically impossible to survive in frontline children’s local authority social work. I have been a social worker in a frontline team for just over 3 years since qualifying, recently promoted and am close to burnout. I think of myself as quite a robust person. IMO the only way to rescue yourself from leaving this career completely is to go into something less frontline and I am trying desperately hard to do this.

There is so much risk involved in child protection, this paired with instability in teams, lack of support from multiagency colleagues and ill equipped managers mean it is unsustainable to continue without running myself into the ground and ruining my mental health. My small, South West LA is so focused on rebuilding our worst hit front door teams that the locality teams are falling apart and suffering with senior managers seemingly taking no notice.

Unless we do what the nurses are doing, taking strike action

None of this comes as any surprise and yet nothing will be done. Working conditions are appallingly, pay is poor for the level of responsibility and risk carried and we are constantly fed untruths by our leadership that things are getting better but they are not.

I will be retiring at the earliest opportunity, as will most of my colleagues. Without drastic changes the situation is only going to get worse for recruitment not better.

It has been like this for the past decade at least and feels like it os getting worse with every year that goes past. I dont think this is simply about the pay anymore- it’s LA structures that push everything down onto the front line worker.

In the light of these perennial reports of excessive workloads and high stress levels, would you recommend to a young person (especially a young man) that they should embark on a career in social work?

Hi Andy

I would not recommend the young man embark on a career in Social Work if he is hardworking, caring , emphatic. conscientious, considerate, analytical.

On the other hand if he is: ambitious above his abilities, and timescales (to learn and reflect); prone to bullying, not analytical, uncaring and wears the Emperor’s New Clothes Social Work may be a good career for the young man because he will likely gain promotion swiftly and rapidly, thus able to place the stress and blame on others of the above characteristics still on the frontline.