This article is part of a series of profiles of key figures who have shaped social work over the past five decades, to mark Community Care’s 50th anniversary. Previous interviewees include Eileen Munro and Herbert Laming.

In 2013, social work lost a generation-defining academic and social worker, with the death of Olive Stevenson.

During 60 years in the profession, Stevenson trained hundreds of practitioners, while simultaneously challenging and inspiring the field through her numerous books and research papers.

She is perhaps best known for her involvement in the historic 1974 inquiry into the death of seven-year-old Maria Colwell, who was murdered by her stepfather after being returned to her mother’s care.

The inquiry, which criticised decision making and practice in the case, triggered media and public hostility towards Maria’s social worker. While Stevenson agreed with the bulk of the committee’s findings, she wrote a minority report dissenting from some of its analysis.

A 2014 article in The Guardian on her career said her report raised concerns about the pressures on the social worker in the case.

“I wish to emphasise that children are at risk in society when social workers, whose concern and dedication is not in doubt, are overloaded,” the report wrote.

A decade after her death, social work professors David Howe, June Thoburn, and Ray Jones – each influential in their own right – reflect on Stevenson’s profound impact on their careers and the profession as a whole.

Ray Jones: ‘She was an active champion for social workers’

I came to know Olive personally when I was appointed as a professor of social work at Kingston University in 2008. She was an honorary professor there at the time.

I was already in awe of Olive. I qualified in 1972, shortly before the Maria Colwell inquiry in 1974, whose impact was significant for all of us within social work. It shaped how the public saw us and how our work was skewed towards child protection.

Olive, bravely, as a member of the inquiry panel, contributed a minority report that illustrated the complexity and uncertainty embedded in the work we do as social workers.

Forty years later, Olive was still an active champion for social work and social workers. Each year at Kingston University’s annual social work conference, she contributed 15 minutes on ‘reflections for today’. Unscripted but, as always with Olive, the outcome of serious thought and preparation, it was always riveting and relevant.

Celebrate those who’ve inspired you

For our 50th anniversary, we’re expanding our My Brilliant Colleague series to include anyone who has inspired you in your career – whether current or former colleagues, managers, students, lecturers, mentors or prominent past or present sector figures whom you have admired from afar.

Nominate your colleague or social work inspiration by either:

- Filling in our nominations form with a letter or a few paragraphs (100-250 words) explaining how and why the person has inspired you.

- Or sending a voice note of up to 90 seconds to +447887865218, including your and the nominee’s names and roles.

If you have any questions, email our community journalist, Anastasia Koutsounia, at anastasia.koutsounia@markallengroup.com

I visited Olive in her home in the Cotswolds quite regularly after she had a stroke in 2010. She was welcoming and great company, remained informed about, and concerned for, social work and was angered by how the media continued, as in 1974, to harass and vilify social workers.

Olive had a keen intellect, but one always used to inform the practical. Her research – often conducted with her close personal friend, Phyllida Parsloe – was always meticulous and with messages for practice and its organisation. Whether about how services were organised or the nature of child neglect or the abuse of older people, there were sensible steers to inform social work and its development.

Olive was generous with her time and with her wisdom. A true doyen of social work.

Ray Jones is emeritus professor of social work at Kingston University and the author of ‘A History of the Personal Social Services in England: Feast, Famine and the Future’ (Palgrave Macmillan 2020)

David Howe: ‘Her social work philosophy sustained my career’

Along with most child and family social workers in the mid-1970s, I first became aware of Olive Stevenson as a member of the inquiry into the death of seven-year-old Maria Colwell at the hands of her stepfather.

In matters of practice and policy, she was showing that social workers could have a voice that was both strong and independent.

It was a few years later, in 1979, that I first found myself in the presence of Olive, at a lecture she was delivering. Three years earlier I had switched jobs from local authority social worker to university lecturer. A requirement of the new job was to research and write papers.

Olive Stevenson (photo by Kingston University)

My very first journal article had just been published and Olive, not knowing I was in the audience, made a brief mention of the paper. Well, I was thrilled. To be name-checked by Olive! Oh my.

However, Olive’s influence on me ran deeper than a moment’s flattery. Along with my colleague and friend, professor Martin Davies, she demonstrated that if social work was to gain academic respectability, it had to be research-driven and evidence-based as well as practice-savvy.

She once wrote that ‘social workers are brokers in shades of grey’. This struck me as deeply true and the thought influenced much of my own thinking, research and writing.

But, perhaps the strongest influence, was Olive’s belief that reflectivity, sensitivity and the social work relationship lie at the heart of good practice. One way or another, this belief has sustained much of my own career and, for that, I owe Olive a lifetime of thanks.

David Howe is emeritus professor of social work at the University of East Anglia and has published widely on subjects including child abuse, neglect, attachment and adoption.

June Thoburn: ‘She did not duck controversial questions’

As a student in 1962-3 on the child care officer course Olive Stevenson set up in Oxford, and throughout my 50+ years as a social worker, educator and researcher, she has been a source of wisdom and ethical guidance.

Her contribution to the profession, and practitioners, ranged across most aspects of social work with children and adults.

She did not duck controversial questions, as seen in her 1974 minority report on the death of Maria Colwell.

Across the years she identified the challenges of being a social worker, educator and researcher and of seeking out answers to the complexities of combining head and heart, past wisdom and new knowledge, practical help and therapeutic skills

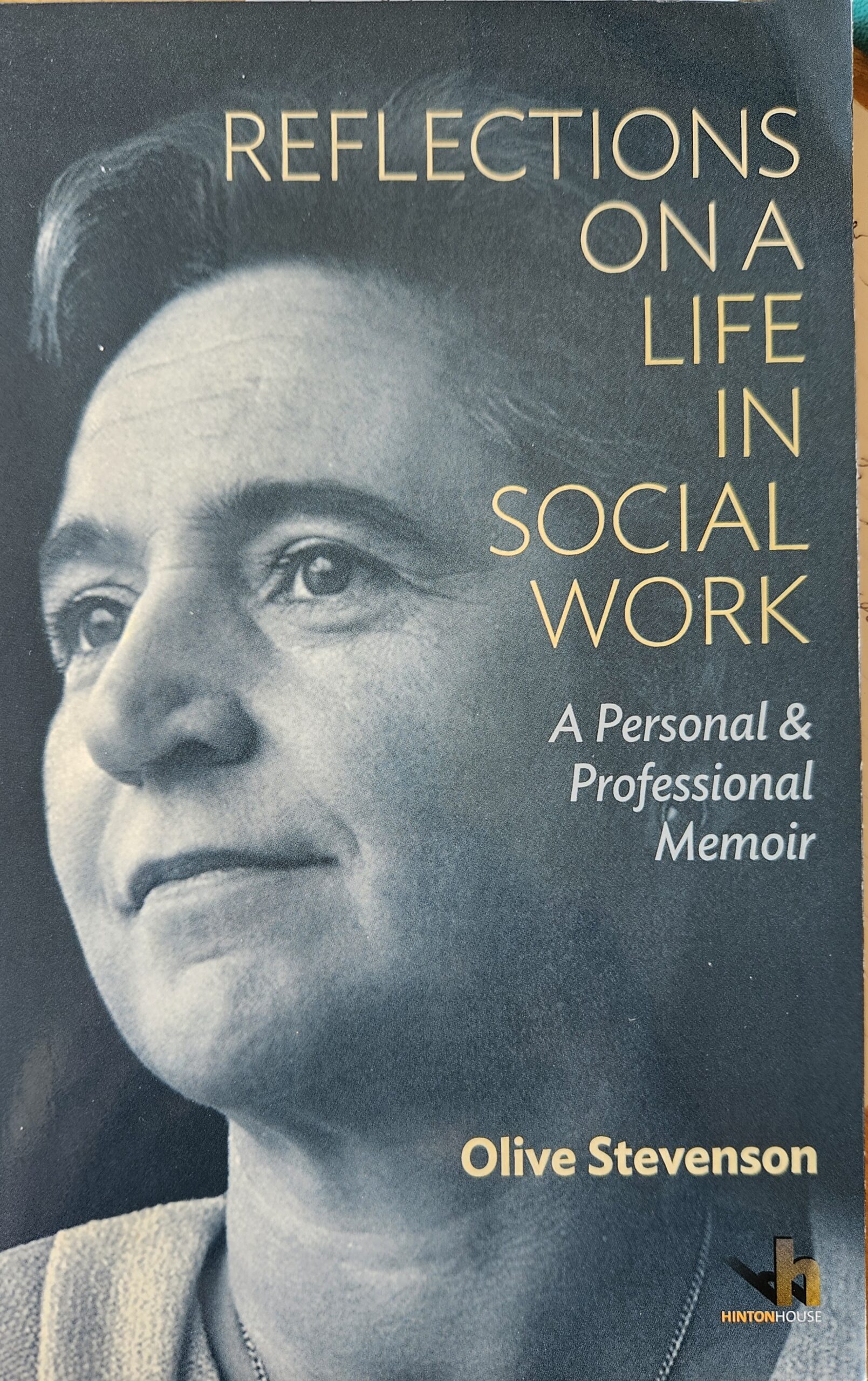

Olive Stevenson’s memoir (photo by David Howe)

In 1999, in her book, Child Welfare in the United Kingdom, she advised us to resist becoming ‘single method’ practitioners, pointing to the complex, sensitive work required when responding to the needs of children,

The essence of Olive’s personal, professional and intellectual contribution is to be found in her 2013 memoir, Reflections on a Life in Social Work. But I also acknowledge her generosity in cataloguing online her many unpublished conference lectures and book chapters, which would otherwise have been lost.

When invited to speak at the celebration of her life at Nottingham University in 2014, I pulled out the following quotes that encapsulate, much better than I can, Olive Stevenson’s enduring contribution:

‘How best, in seeking to help others, to use one’s mind and one’s feelings together, has remained a central preoccupation of my professional life.

(Memoir, p60)

‘I was never in doubt that the essence of social work skill lay in some combination of reflective and practical work WITH and FOR the person in need of help’ (Memoir, 78).

Olive always remained an advocate for the ongoing necessity for ethical, knowledge-informed, inclusive and poverty-aware practice.

June Thoburn is emeritus professor of social work at the University of East Anglia. Her extensive research into child protection and family support has focused, in particular, on the views of children, parents, foster carers and adopters on the services they are offered.

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole

Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole  Hampshire County Council

Hampshire County Council  Lincolnshire County Council

Lincolnshire County Council  Norfolk County Council

Norfolk County Council  Northamptonshire Children’s Trust

Northamptonshire Children’s Trust  South Gloucestershire Council

South Gloucestershire Council  Wiltshire Council

Wiltshire Council  Wokingham Borough Council

Wokingham Borough Council  Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors

Children and young people with SEND are ‘valued and prioritised’ in Wiltshire, find inspectors  How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers

How specialist refugee teams benefit young people and social workers  Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent

Podcast: returning to social work after becoming a first-time parent  Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?

Podcast: would you work for an inadequate-rated service?  Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

I was so lucky to meet her and talk at some length with her. She was so generous towards those of us whom she saw as the younger generation but I also loved how she challenged me! For example, she thought that my commitment to engaging men was slightly naive and told me so. But she also encouraged me enormously.

A fabulous woman, a lesbian, a scholar, kind and wise. What a role model!

It saddens me to be reminded that far from valuing insights and wisdom Olive Stevenson gifted us we are led by comparative non-entities who struggle to comprehend what not being “single method practitioners” means.