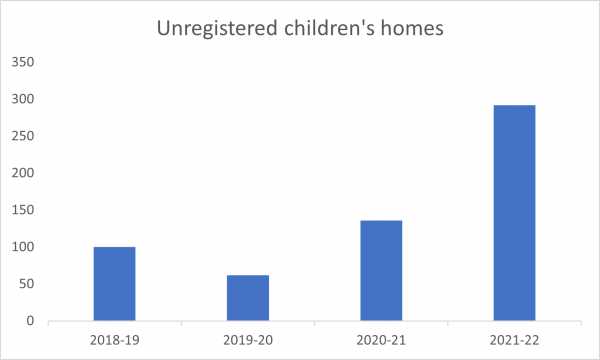

The number of unregistered children’s homes identified by Ofsted more than doubled from 2020-21 to 2021-22, the regulator has revealed.

In in its annual children’s social care data report, published last week, Ofsted said it had found 292 settings that should have been registered as children’s homes following investigation in 2021-22, up from 136 in 2020-21. The 2020-21 figure was itself significantly up on the previous two years.

Number of settings found to be unregistered children’s homes by Ofsted (2018-19 and 2019-20 figures are approximate)

At the same time, the number of children waiting for a bed in England’s 13 secure children’s homes each day has doubled from 25 to 50, according to figures supplied to Ofsted by the Secure Welfare Coordination Unit, which administers placements.

Ofsted’s report also showed an increase in the number of children’s homes actively registered to provide one bed, from 106 to 164, between 2020-21 to 2021-22.

All three trends illustrate the scale of the pressures on councils to find placements for children who need secure or specialist care because of the complexity of their needs or the risks they face – for example, from exploitation.

462% rise in deprivation of liberty orders

The lack of beds for children who meet the criteria for a secure order under section 25 of the Children Act has forced councils to, increasingly, seek court orders to deprive of them of their liberty in other settings. These rely on the inherent jurisdiction of the High Court to protect children where no statutory provision is available.

The number of such deprivation of liberty (DoL) orders – which are also sought for children who do not meet the section 25 criteria – rose by 462% from 2017-18 to 2020-21.

These often involve setting up bespoke placements that – because they provide accommodation with care – are legally required to be registered as a children’s home. The courts will only authorise such unregistered placements in an emergency and if providers are taking steps to secure registration with Ofsted.

The regulator said that most of the 292 settings it identified as unregistered homes in 2021-22 had been sent warning letters though some will have stopped operating.

More single-bedded homes

Single-bed children’s homes are also used as an alternative to secure care. The number of registered single-bed homes underestimates the number of children living in solo placements as it excludes those placed in larger homes where all other beds are empty.

Responding to the data, Association of Directors of Children’s Services vice president John Pearce said it illustrated the challenges local authorities faced in finding – often at short notice – secure placements for children “in extreme distress”.

He said there had been an increase in the number of children with substantial mental health needs in this group, which Pearce suggested may have been caused by reductions in tier 4 Camhs beds for children in the most acute need.

“Where a secure placement cannot be found or the young person’s needs are so severe they are unable to live with other children, a single bedded children’s home has become the only option,” he added.

However, he said that, while matching children and young people together in multi-bed homes was critical, “so is ensuring that children and young people have the opportunity to develop and nourish positive peer relationships as this is in their best interests”.

Concerns over smaller settings

Yvette Stanley, Ofsted’s national director for social care, voiced similar concerns about growing numbers of single-bed placements and vacancies in larger homes, at last week’s ADCS annual conference.

“We no doubt need smaller homes to meet the needs of children who need two or three to one support, a low sensory environment and who might struggle with the needs and behaviours of others,” she said.

Related articles

However, she said she was worried about “perhaps creating too many single child homes, where some safeguards may be more difficult to deliver and where the loss of social interaction with peers in the longer term may cause different harm”.

Stanley also raised concerns about children’s homes carrying vacancies because of the “pursuit of the perfect match”, which was pushing up costs for local authorities.

‘A risk-averse approach’

She said some providers were concerned about the consequences for their inspection rating of taking children with particularly complex needs – despite inspectors’ focus being on how those needs are met.

“I am hearing more often of providers looking to move children of a particular need on, and local authorities competing financially for one empty place,” she told the ADCS conference. “The numbers and needs have increased, and yet we see places held vacant.”

She added: “We don’t want to see a risk-averse approach that leaves children with the most complex needs less likely to receive the kind of care they need.”

Stanley’s warnings about vacancies chime with the findings of a survey of providers, published last month by the Independent Children’s Home Association.

This found homes were prioritising good matching over occupancy, amid concerns over their ability to meet children’s increasingly complex needs, given the need to safeguard their other young people.

They also cited concerns about putting their Ofsted rating at risk, councils’ increasing requirement for solo-placement homes and a lack of suitable staff, which Stanley also referred to in her speech.

Mismatch of home locations and need

Meanwhile, a separate Ofsted report issued last week found a mismatch between the location of children’s homes, the provision they could offer, and children’s needs.

While a quarter of children’s homes were in the North West, and 19% in the West Midlands, councils from these regions were responsible for placing 19% and 12%, respectively, of children in homes, as of March 2020.

By contrast, London housed 5% of homes but the capital’s authorities placed 11% of children.

Disparities were also apparent in relation to homes’ ability to meet certain needs. For example, while having a quarter of homes overall, the North West had only 18% of homes catering for autistic children.

Overall, the roughly 6,000 young people in homes were placed an average of 36 miles from where they lived prior to coming into care – compared with 13 miles for those in foster care. The average distance was higher for those placed in homes that could meet the needs of children with mental health needs (44 miles) and those who could accommodate children who had experienced abuse or neglect (42 miles).

‘A vicious cycle’

On behalf of the ADCS, Pearce added: “The uneven distribution of homes across the country is an added challenge with homes frequently opening up where housing is cheaper not where they’re needed most, as is the unwillingness of some providers to take children with any level of complexity for fear of the impact on their Ofsted rating.

“This can mean children and young people with complex needs, who are equally deserving of our love, care and support, are placed miles away from their friends, families and communities or in a home on their own and sometimes in unregulated provision. This is not in the best interests of children, and it has a knock-on effect on the availability of homes and local authority budgets. It’s a vicious cycle.”

In its report, Ofsted said that the location of homes was likely a product of the lack of a national plan as councils withdrew from providing homes and private sector provision expanded over the past two decades.

It said two studies had found there was not a close relationship between house prices and the location of homes – though this was rejected by the Independent Review of Children’s Social Care, in its final report in May. The regulator said there was scope for more research into the topic.

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  ‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services

‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services  How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence

How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence  How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families

How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

surprise surprise (scouse accent) does the quango game Ofsted hold LA’s to sufficiency account ?