“Getting the basics right” around social work has been key to year-on-year improvements in council performance in children’s services, an Ofsted leader has said.

Yvette Stanley’s comments came as the inspectorate’s latest annual report showed 60% of the 153 English authorities were rated good or outstanding for children’s services as of September this year.

This is a rise from 56% at the same time in 2022, 51% in 2021 and 50% in 2020.

Performance under the current inspection of local authority children’s services (ILACS) framework is also significantly better than under the previous single inspection framework (SIF), which was in place up to the end of 2017. Just 36% of authorities were rated good or outstanding after their first SIF inspection.

‘Getting the basics right’ key to improvement

In its report, Ofsted said there was “no one reason” for councils’ improved performance but said it had seen authorities “investing in strengths-based models of social work with families” and “setting clear direction for their social work teams”.

Expanding on these points, Stanley, Ofsted’s national director for social care, attributed the progress to “stable leadership, a clear practice model that keeps children front and centre and creating the right environment for social workers to do their best work, the importance of manageable caseloads, and the support around social workers – the administrative systems – so they can spend more time doing direct work with children”.

“It’s about getting the basics right,” she added. “We’ve seen significant improvements in those areas.”

New care leaver judgment

This year also saw the introduction of a separate judgment in relation to councils’ services for care leavers, which has been decoupled from a previous joint category encompassing looked-after children’s provision.

Of the 26 authorities rated on the measure, 57% were rated good or outstanding, with 13 having a different grade from their performance for children in care.

Photo: Valerii Honcharuk/Adobe Stock

“These differences in quality were less visible under the previous combined judgement, Ofsted said. “We are now more easily able to highlight good and poor practice for these distinct groups and make more targeted recommendations.”

Councils’ overall progress comes despite a hugely challenging backdrop for children’s social care, which was highlighted in the report.

Rising social work vacancy and agency rates

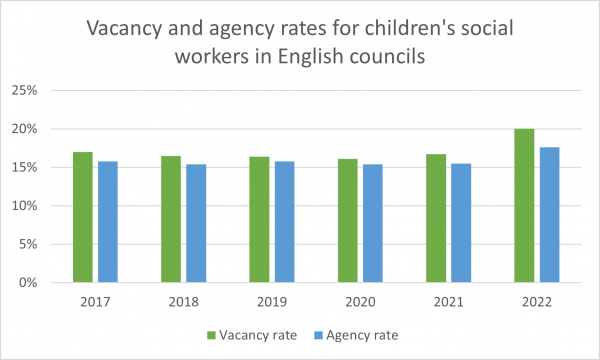

The council children’s social worker vacancy rate rose from 16.7% to 20%, and the agency staff rate from 15.5% to 17.6%, in the year to September 2022, following years of relative stability.

Source: Department for Education children’s social work workforce census, 2022

Ofsted said there was an “overreliance on agency social workers which undermines the consistency of the support that children experience”.

The Department for Education (DfE) is planning to introduce national rules to reduce councils’ use of agency social workers in children’s services, however, it has diluted its original plans following a consultation.

Placement shortage amid rising care population

The inspectorate also flagged up the ongoing challenges councils faced in securing sufficient appropriate care placements, in the context of a 15th year of rising numbers of looked-after children.

As it reported earlier this month, the number of mainstream fostering households shrank for a second consecutive year in 2022-23.

And while the number of registered children’s home places rose by 5% in 2022-23, following a 4% increase in 2021-22, Ofsted said that the location of new homes did not match children’s needs.

“Homes continue to open disproportionately in the regions where numbers are already the highest,” said the annual report. “The North West accounts for a quarter of all children’s homes and almost a quarter of all places.”

Illegal use of unregistered homes

The shortage of placements was leading to some children being placed in unregistered children’s homes, which are illegal.

As has been well-documented, these have been used for the rapidly-rising number of children who need to be deprived of their liberty but who cannot be placed in secure children’s homes, for which 50 children are waiting for each place at any one time.

But Ofsted said unregistered placements were also used as a “stop-gap” for other children who could not be placed elsewhere.

“Although these homes are often a last resort and intended to be temporary, the national shortage of placements for children with complex needs means some particularly vulnerable children live in these settings for long periods,” it said.

It said it completed 530 investigations into possible unregistered homes during 2022-23, in most cases after being notified by the placing local authority.

In 370 cases (70%), the home should have been registered, resulting in Ofsted sending the provider a warning letter. In most of these cases, the home then stopped operating.

Concerns about solo placements

Ofsted also found that an increasing number of homes were operating below capacity. In some cases, this was because councils were commissioning solo placements – because of the complexity of a child’s needs – and in others, it was due to homes struggling to recruit staff.

Photo: Presidentk52/Fotolia

While it said solo placements were right for some children, Ofsted added that it was “concerned at the continuing rise in children living alone and with very high staffing numbers”.

On staffing, it said 35% of care staff in children’s homes left their posts during 2022-23 – the same proportion as in 2021-22 – reducing young people’s chances of “building the relationships that are important for [their] wellbeing and sense of belonging”.

Fall in proportion of qualified staff

Providers and councils reported that staff in roles that required few or no qualifications were moving to better-paid jobs in other industries, while more qualified workers were moving into higher-paid agency roles.

Half of children’s homes staff held a required level 3 qualification (54%), down from 61% four years ago.

And while the proportion of registered children’s home managers holding the mandatory level 5 qualification has increased from 50% to 64% since 2018-19, 12% of homes did not have a manager in place as of the end of 2022-23.

“This leaves a significant gap in oversight of what is happening for children,” the report added.

Impact of ending unregulated provision

Council leaders have also raised concerns that the introduction of regulation of semi-independent settings for 16- and 17-year-olds – now renamed ‘supported accommodation – will worsen the sufficiency problem.

Councils’ use of such placements has grown significantly over the past two years. However, providers were only expected to register four out of every five semi-beds they previously operated with Ofsted, found a report published in July by the County Councils Network (CCN) and London Innovation and Improvement Alliance.

(credit: caracoot / Adobe Stock)

Ofsted said that, as of the deadline of 28 October, 2023, 680 providers, operating 5,930 settings, had been registered or had applied to do so.

It also received 43% more applications to register children’s homes in 2022-23 compared with 2021-22 (630, up from 440) and suggested some of these may have been from former semi-independent settings.

“Extending regulation to all provision means that existing providers are deciding whether to register children’s homes or as a supported accommodation provider,” Ofsted added.

Targeted early help concerns

Outside of care placements, Ofsted’s annual report also raised concerns about targeted early help services, based on thematic inspections carried out with fellow inspectorates earlier this year and at the end of 2022.

While it found “well-trained and knowledgeable early help workers undertaking effective work”, Ofsted added that in some areas lead professionals lacked the skills and knowledge required for the risks the children they worked with faced.

Stanley told Community Care: “We are seeing very little early help in some areas. That’s sadly leaving families in the preventative space losing out.”

The annual report comes with the DfE planning a raft of reforms to children’s social care, including to improve the sufficiency of care placements and the quality and capacity of family support.

Children’s social care reforms

In regard to the latter, the department is testing bringing together targeted early help and child in need services into a single family help service. This will involve, among other things, enabling non-social work staff to carry child in need cases, which is currently prohibited by the Working Together to Safeguard Children guidance.

Ofsted has previously raised concerns about this change potentially increasing risks to children.

“We see benefits in a system that brings targeted early help and child in need work together,” Ofsted said in its annual report. “Managing risk carefully and making sure that the system does not become overwhelmed will require careful work and good oversight, especially given that the workforce is already stretched.”

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model

Family help: one local authority’s experience of the model  ‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services

‘I spent the first three months listening’: how supportive leadership can transform children’s services  How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence

How senior leaders in one authority maintain a culture of excellence  How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families

How staff support ensures fantastic outcomes for children and families  Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Workforce Insights – showcasing a selection of the sector’s top recruiters

Facebook

Facebook X

X LinkedIn

LinkedIn Instagram

Instagram

Getting the basics right must include an end to FII accusations and disciplinary action taken against SWs who continue to perpetrate lasting harm against children and families by colluding with these baseless accusations. FII accusations are on the rise, despite the work done by Cathleen Long, and Prof Luke Akehurst for Cerebra. https://cerebra.org.uk/research/fabricated-or-induced-illness-research-report/?fbclid=IwAR31KkzsiNhI8Fg5fW_jicvIoPoY5FNwdG6Gkvp8bLgW6iK38kXsM76YPK4

Also, current Ofsted workers alerting previous employees of Ofsted when their authorities are due to be inspected and so there’s a mad rush to tidy up the last 6months of data as that all Osted looks at